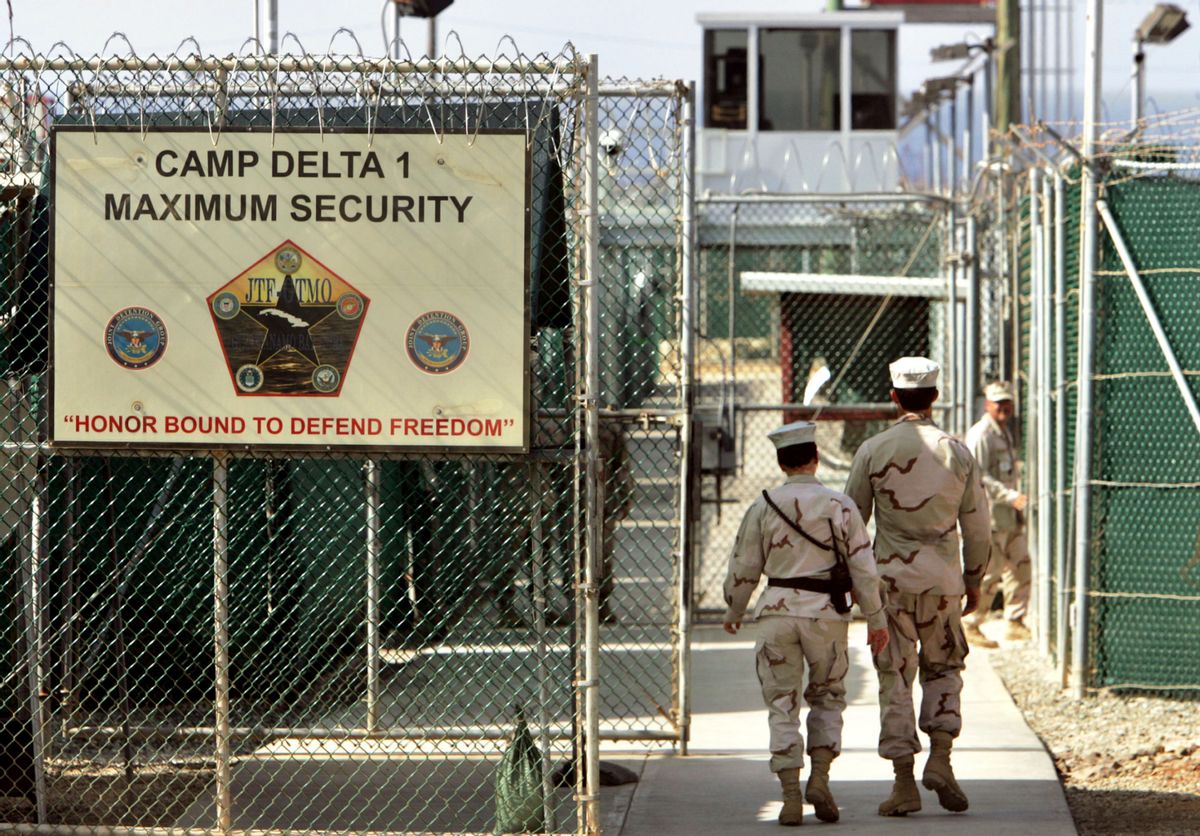

Eight years ago, when I wrote a book on the first days of Guantanamo, "The Least Worst Place: Guantánamo’s First 100 Days," I assumed that Gitmo would prove a grim anomaly in our history. Today, it seems as if that “detention facility” will have a far longer life than I ever imagined and that it, and everything it represents, will become a true, if grim, legacy of twenty-first-century America.

It appears that we just can’t escape the perpetual pendulum of the never-ending war on terror as it invariably swings away from the rule of law and the protections of the Constitution. Last month, worries that had initially surfaced during the presidential campaign of 2016 over Donald Trump’s statements about restoring torture and expanding Guantanamo’s population took on a new urgency. In mid-September, the administration acknowledged that it had captured an American in Syria. Though no facts about the detained individual have been revealed, including his name or any allegations against him, the Pentagon did confirm that he has been classified as an “enemy combatant,” a vague and legally imprecise category. It was, however, one of the first building blocks that officials of George W. Bush’s administration used to establish the notoriously lawless policies of that era, including Guantanamo, the CIA’s “black sites,” and of course “enhanced interrogation techniques.“

Placing terrorism suspects apprehended while fighting abroad in American custody is hardly unprecedented. The U.S. government has periodically captured citizen and non-citizen members of ISIS, and fighters from the Somali terrorist organization al-Shabaab, as well as from al-Qaeda-linked groups. To those who have followed such matters, however, the Trump administration’s quick embrace of the term “enemy combatant” for the latest captive is an obvious red flag and so has elicited a chorus of concern from national security attorneys and experts, myself included. Our collective disquiet stems from grim memories of the extralegal terrorism policies the Bush administration institutionalized, especially the way the term “enemy combatant” helped free its officials and the presidency from many restraints, and from fears that those abandoned policies might have a second life in the Trump era.

Guantanamo’s detainees

What, then, is an enemy combatant? After all, memories fade and the government hasn’t formally classified anyone in custody by that rubric since 2009. So here’s a brief reminder. The term first made its appearance in the early months after 9/11. At that time, then-Deputy Assistant Attorney General John Yoo — who gained infamy for redefining acts of torture as legal “techniques” in the interrogation of prisoners — and others used “enemy combatant” to refer to those captured in what was then being called the Global War on Terror. Their fates, Yoo argued, lay outside the purview of either Congress or the courts. The president, and only the president, he claimed, had the power to decide what would happen to them.

“As the president possess[es] the Commander-in-Chief and Executive powers alone,” Yoo wrote at the time, “Congress cannot constitutionally restrict or regulate the president's decision to commence hostilities or to direct the military, once engaged. This would include not just battlefield tactics, but also the disposition of captured enemy combatants.”

The category, as used then, was meant to be sui generis and to bear no relation to “unlawful” or “lawful” enemy combatants, both granted legal protections under international law. Above all, the Bush version of enemy-combatant status was meant to exempt Washington’s captives from any of the protections that would normally have been granted to prisoners of war.

In practice, this opened the way for that era’s offshore system of (in)justice at both the CIA’s black sites and the prison camp at Guantanamo, which was set up in Cuba in order to evade the reach of either Congress or the federal court system. The captives President Bush and Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld sent there beginning in January 2002 fell into that category. In keeping with the mood of the moment in Washington, the U.S. military personnel who received them were carefully cautioned never to refer to them as “prisoners,” lest they then qualify for the legal protections guaranteed to prisoners of war. Within weeks, the population had grown to several hundred men, all labeled “alien enemy combatants,” all deemed by Yoo and his superiors to lie outside the laws of war as well as those of the United States, and even outside military regulations.

American citizens were excluded from detention there. Some were nonetheless labeled enemy combatants. One — Jose Padilla — was arrested in the United States. Another — Yaser Hamdi — was initially brought to Gitmo after being captured in Afghanistan, only to be flown in the middle of the night to the United States as administration officials hoped to escape public attention for their mistake.

Padilla had been born and raised in the United States; Hamdi had grown up in Saudi Arabia. To avoid the federal detention system, both would be held in a naval brig in South Carolina, deprived of access to lawyers, and detained without charge. For years, their lawyers tried to convince federal judges that keeping them in such circumstances was unconstitutional. Eventually, the Supreme Court weighed in, upholding Yoo’s position on their classification as enemy combatants, but allowing them lawyers who could challenge the grounds for and conditions of their detention.

Although the government defended the use of enemy combatant status for years, both Padilla and Hamdi were eventually — after almost three years in Hamdi’s case, three and a half for Padilla — turned over to federal law enforcement. Never charged with a crime, Hamdi would be returned to Saudi Arabia, where he promptly renounced his U.S. citizenship, as the terms of his release required. Padilla was eventually charged in federal court and ultimately sentenced to 21 years in prison.

By the time Barack Obama entered the Oval Office, both cases had been resolved, but that of another enemy combatant held in the United States, though not a citizen, was still pending. Ali Saleh al-Marri, a Qatari and a graduate student at Bradley University in Illinois, was taken from civilian custody and detained without charges for six years at the same naval base that had held Padilla and Hamdi. Within weeks of Obama’s inauguration, however, he would be released into federal civilian custody and charged. Meanwhile, in June 2009, for the first and only time, the Department of Justice suddenly transferred a Guantanamo prisoner, Ahmed Ghailani, to federal custody. A year later, he was tried and convicted in federal court for his involvement in the 1998 bombings of the U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania.

The message seemed hopeful, and was followed by other potentially restorative gestures. On the day Obama entered the White House, for instance, he signed an executive order to close Guantanamo within the year. In March, he abandoned the use of the term enemy combatant for the detainees there. Aiming to release or try all who remained in that prison camp, he appointed a task force to come up with viable options for doing so.

In other words, as his presidency began, Obama seemed poised to restore rights guaranteed under the Constitution to all prisoners, including those in Guantanamo, when it came to detention and trial. The pendulum seemed potentially set to swing back toward the rule of law. In the years to come, there would, nonetheless, be many disappointments when it came to the rule of law, including the failure to close Guantanamo itself. There was, as well, the Obama administration’s 2011 reversal of its earlier decision to take the alleged 9/11 co-conspirators — including the “mastermind” of those attacks, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed — into federal court rather than try them via a Gitmo military commission.

In reality, that administration would even end up preserving an aspect of the enemy-combatant apparatus. In 2011, before bringing Ahmed Abdulkadir Warsame, a Somali defendant, and in 2014 before bringing Abu Khattala, the alleged mastermind in the deaths of an American ambassador and others in Benghazi, Libya, to the United States and putting them in federal custody, and in 2016 before bringing two Americans found fighting in Syria court here, the Obama administration would carve out a period for military detention and interrogation prior to federal custody and prosecution.

In each case, the individuals were held in military custody and first interrogated there. Warsame, for instance, was kept aboard a U.S. Navy vessel for two months of questioning before being charged with, among other things, providing material support to the Somali militant group al-Shabaab and to al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula. (In December 2011, he would plead guilty in a federal court in New York City.) Khattala was held for 13 days. Once U.S. intelligence agents had the information they felt they needed, they turned the detainees over to those who would help prosecute them -- to the “clean team.”

Until the recent Trump administration designation, however, no one in the ensuing years would be newly labeled an enemy combatant and sent to the Guantanamo Bay Detention Facility or held without charge on U.S. soil. In fact, a number of individuals who, in the Bush years, would undoubtedly have become detainees there landed in federal court instead, including bin Laden’s son-in-law, Sulaiman Abu Ghaith, and Abu Hamza al-Masri, an al-Qaeda operative accused of trying to build a terrorist cell in the United States.

As a result, this fall there are a surprising number of terrorism trials taking place, including that of the alleged Benghazi mastermind, of the two Americans who were fighting alongside ISIS in Syria, and of U.S. citizen Muhanad Mahmoud al-Farekh, who was just found guilty in a federal court in Brooklyn, New York, of conspiring to aid al-Qaeda and bomb a U.S. military base in Afghanistan.

In these years, the belief that terrorism suspects belong within the federal criminal justice system was reestablished. In addition, Obama appointed two consecutive special envoys to take charge of transferring detainees cleared for release from Guantanamo, which Congress refused to close. As a result, a total of 197 were released during the Obama years, leaving only 41 in indefinite detention as Trump came into office.

Meanwhile, during the tenures of Attorneys General General Eric Holder and Loretta Lynch, the federal courts would handle an increasingly wide array of terrorism cases, ranging from the Boston Marathon attack to the attempts of a woman in Colorado to travel abroad to marry an ISIS member and serve the caliphate. Taken together, these developments seemed to signify an end to the era of indefinite detention and of detention without charge. Or so we thought.

Back to the future

Now, it seems, the term “enemy combatant” is back and who knows what’s about to come back with it? Was the Trump administration’s very use of that label meant to get our attention, to signal the potential Guantanamo-ish future to come, to quash any cautious hopes that the modest gains realized during the Obama years might actually last? Remember that, during the 2016 election campaign, Donald Trump swore that he would add some “bad dudes” to Guantanamo and insisted that even American citizens could end up in that persistent symbol of American injustice.

In the meantime, in August it was revealed that the Pentagon was already requesting from Congress $500 million dollars to build new barracks for troops, a hospital, and a tent city for migrants at Gitmo. In other words, the United States now stands at a worrisome and yet familiar crossroads in its never-ending war on terror and the signs point to a possible revival of some of the worst policies of the national security state.

In reality, so many years later, enemy combatant status should be a nonstarter, a red flag of the first order, as should indefinite detention. In the past, such policies produced nothing but a costly quagmire, leaving George Bush to personally release more than 500 detainees, Barack Obama nearly 200, and the government to eventually take citizens declared to be enemy combatants out of military custody and transfer them to federal court. Meanwhile, the hapless military commissions tied directly to Gitmo that were to replace the federal court system have yet to even begin the trials of the alleged co-conspirators of 9/11, while such courts have already tried more than 500 terrorism defendants.

Is this really what the Trump years have in store for us? A return to a policy that never worked, that brought shame to this country, cost a fortune in the bargain (at the moment, nearly $11 million annually per Gitmo detainee), and undermined faith in the federal court system, even though those courts have proved so much more capable than the military commissions of dealing with terrorism cases?

For those of us who thought this country might have learned its lesson, the use of the term “enemy combatant” for new detainees and for an American citizen is more than a provocative gesture, it’s the latest attack on the rule of law. It represents a renewed attempt to dismantle yet another piece of the fabric of American democracy and to throw into doubt a founding faith in the importance of courts and the judicial system. It’s another reminder that the rise of the national security state continues to take place outside the bounds of what was once thought of as fundamental to the republic — namely, institutions of justice. Suitably, then, the American Civil Liberties Union filed a habeas petition on October 5th challenging the detention of the newest enemy combatant, asserting, among other things, “John Doe’s” right to an attorney and calling for him to be transferred into civil custody and charged or released.

Though the future is so often a mystery, if the Trump administration goes down this same path again, it should be obvious from the last decade and a half just where it will lead: toward a renewed policy of legal exceptionalism in which the American scales of justice will once again be decisively tipped toward injustice.

Shares