President Donald Trump has issued the first of what promises to be a series of health insurance executive orders aimed at dismantling the Affordable Care Act.

It instructs the government to essentially exempt small businesses and potentially individuals from some of the rules underpinning the landmark legislation known as “Obamacare,” following the GOP’s failure to get Congress to approve a plan to repeal and replace it.

These steps would free more employers to access bare-bones and short-term health insurance coverage and join together to bargain with insurers. It’s not clear how this order will change the U.S. health insurance market. But as a health finance professor and the former CEO of an insurance company, I’m confident it is more likely to compound many of Obamacare’s problems than to fix them.

Designed this way

To be sure, the Affordable Care Act has problems. For example, premiums have continued to rise since the Affordable Care Act’s enactment – albeit at a moderate pace for insurance obtained through employment.

In particular, many smaller employers have seen their costs rise dramatically since insurers were forced to price their plans based on the average of all claims in the small group market rather than the experience of each firm.

But there is a reason why Obamacare was designed this way. Employers with older and less healthy workers were almost shut out of the insurance market because insurers deemed them so costly to cover and wanted to avoid the risk. Companies with younger and healthier workers had a good deal previously, but many other employers did not.

The Affordable Care Act was supposed to solve this problem by lumping everyone together to even out rates. Making rates more reasonable for many Americans meant requiring some of us to pay more.

Market dynamics

The government’s attempt to keep President Barack Obama’s oft-repeated promise that “if you like your current plan, you can keep it” didn’t help. Employers with low-cost plans and healthier workforces chose to be grandfathered out of many new requirements, leaving a much less healthy – and more expensive to cover – pool for pricing everyone else’s insurance.

Nevertheless, the share of adults without health insurance fell to a record low of 10.9 percent in late 2016, from 18 percent before the health insurance exchanges opened in October 2013, as measured by polling by Gallup and Sharecare. (The uninsurance rate has ticked up to 11.7 percent since Trump took office.)

What would be a good way to get the remaining 28 million Americans insured at a reasonable cost? It may seem obvious that letting small businesses without much purchasing power in the health insurance market band together will enable them to get the same deals as large self-insured companies – which get to choose among a variety of options.

In most markets, this kind of diversity and choice fosters the robust competition Trump says he wants to see. But in health insurance, this may lead to fragmentation and market failure.

That’s because as insurers scramble for ideal customers – those least likely to get sick – they drive higher-risk people away by charging them higher premiums and making them foot a bigger share of their medical bills. Unfortunately, the latter (people often with preexisting conditions and requiring long-term treatment) really need medical care and the insurance coverage required to get it.

Because of this, all but the largest of the association health plans that the executive order is supposed to encourage still will most likely exclude high-risk individuals and employers, just as they have in the past, as health law expert Tim Jost predicts.

How will the vulnerable get health care?

Trump said that his executive order will help “millions and millions of people.” But I believe it is more likely to drive coverage for many out of reach while benefiting the Americans whose insurance needs are relatively minimal.

One could argue that the government should never have tried to force healthier people to pay so much more for coverage to make it affordable for everyone else. Yet the nation needs a mechanism to help Americans with chronic and preexisting conditions pay for the medical care they need.

Establishing high-risk pools is one way to make this work, and they definitely can help as long as there is funding available. Unfortunately, most attempts to handle high-risk individuals this way have run out of money and left vulnerable patients high and dry. Trump’s approach does nothing to deal with this.

Any solution that makes health insurance more affordable across the board will need to be comprehensive. I believe Trump is instead embarking on a process that is both naïve and piecemeal based on wishful thinking regarding the power of markets to resolve all the problems with this difficult sector.

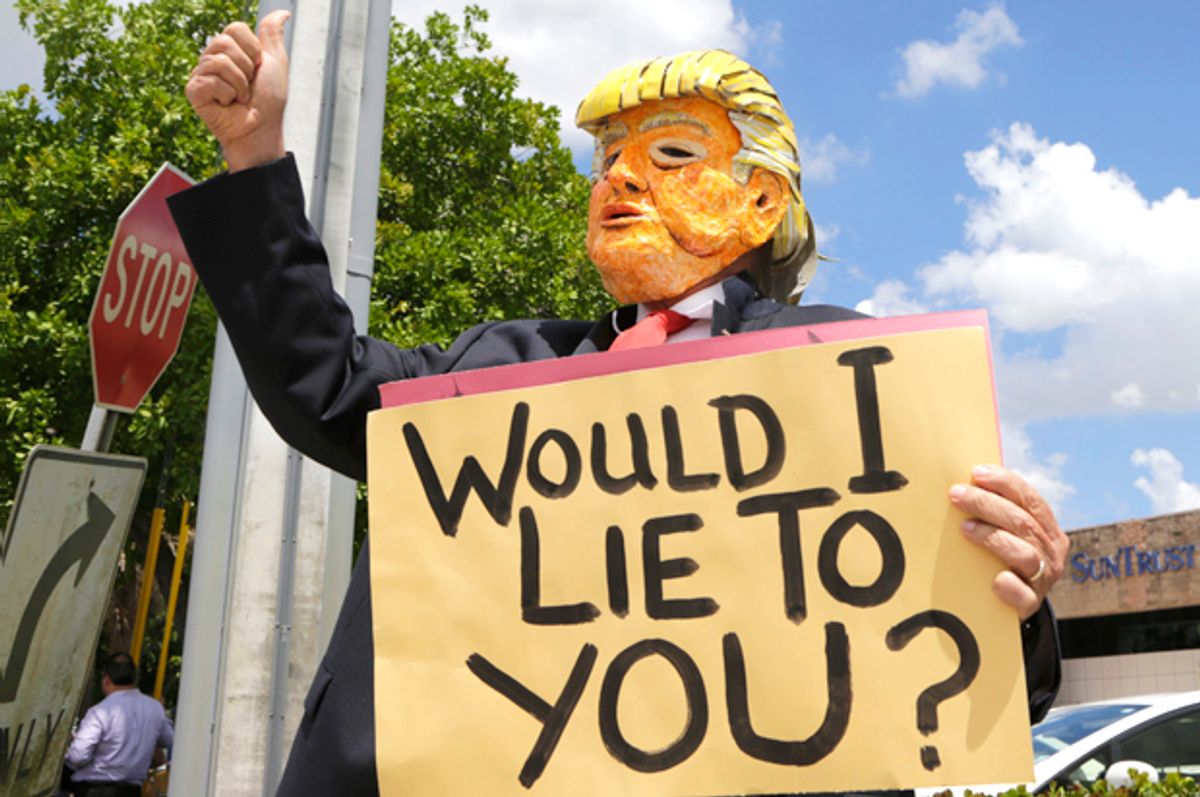

![]() During his signing ceremony, he promised that the policies established by the order would “cost the government virtually nothing.” If that proves true, it is likely that we will receive exactly what we pay for.

During his signing ceremony, he promised that the policies established by the order would “cost the government virtually nothing.” If that proves true, it is likely that we will receive exactly what we pay for.

J.B. Silvers, Professor of Health Finance, Weatherhead School of Management & School of Medicine, Case Western Reserve University

Shares