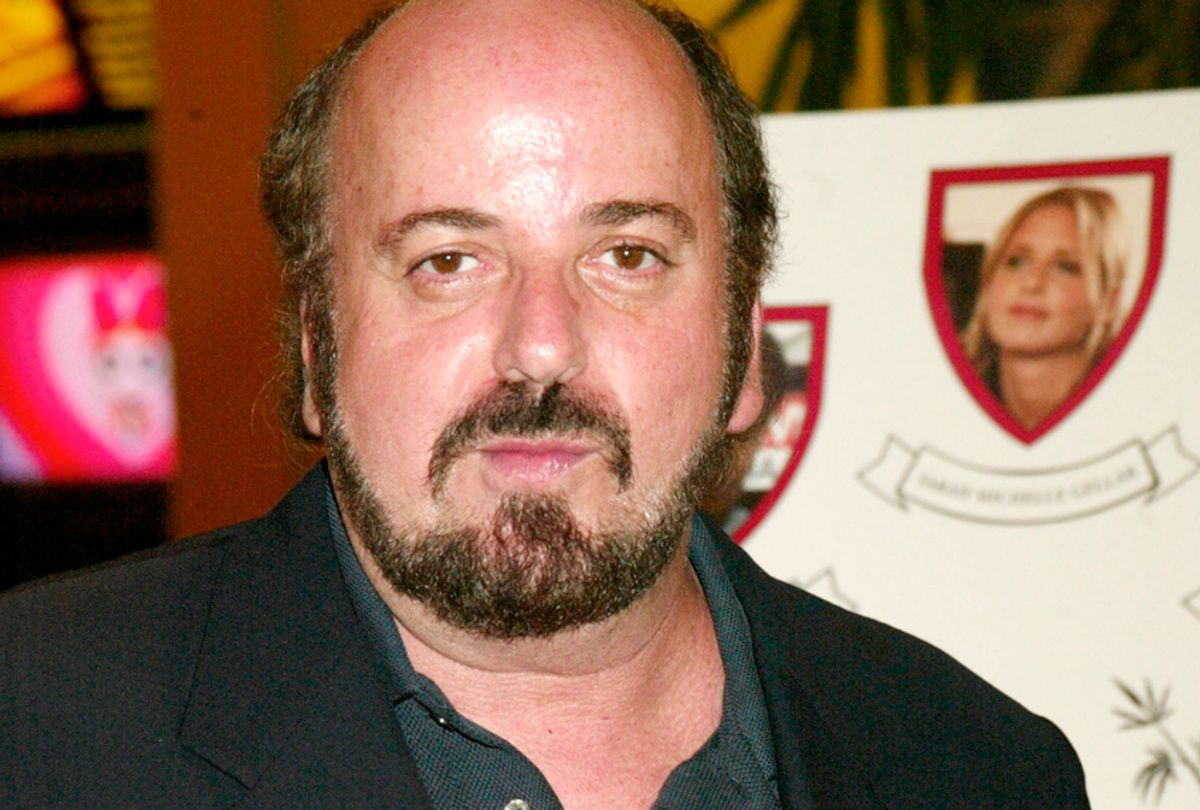

An article in the Los Angles Times published this weekend reported that 38 women alleged that director and writer James Toback either sexually harassed or sexually assaulted them in a pattern of systematic abuse that stretches back decades.

At this point, more women, Julianne Moore included, have stepped forward to join them. With the number of people now claiming Toback abused them in some way shooting up over 200, it seems safe to assume that more will add their stories about his shameful actions.

Just as with the accusations against Harvey Weinstein earlier this month, members of the public and many members of the media are wondering aloud why something wasn't said or done about Toback's allegedly systematized abuse sooner. It's a good question to ask.

The thing is, the media and those in the film industry had spoken up about this possible pattern of harassment and assault before, just in a way that was not helpful.

For those not aware of Toback, the New York-based director has spent a career churning out self-consciously controversial films such as “Black and White” that feature sexual dynamics in ways that could be intriguing to some viewers who are not familiar with his personal life. They can be revolting to those who are.

Male-gaze anchors "When Will I Be Loved." The emotional domination (and moment of nonconsensual sex) of "Two Girls and a Guy," offers unsettling parallels to his alleged behavior, as does the "Pickup Artist.” That many of his lead characters were themselves nominal agents of their own narratives never truly seemed counteract this.

Through Gawker, water-cooler chatter, blind items on often discredited websites, we all knew Toback had what was called back then "a problem with women." Yet, until very recently, nods to these kind of patterns were the best most media outlets could or would do with any celebrity who had "a problem with women."

Libel laws, the cosy relationships entertainment reporters and editors often have with representatives of studios and agencies, the power of these celebrities and the unwillingness of those in the media to listen and report all colluded to make this the case. It was even so with Toback, a director who couldn't boast any real power (though he had powerful friends).

Just look at how Salon's own Catherine Getches constructed an arrow pointing to Toback's behavior in 2002. Reporting only what she sees, she details the very same routine Toback is alleged to have used with his victims, some of whom are now stepping forward.

To Getches Toback was:

As charming as Robert Downey Jr.'s character in "The Pick-Up Artist" (1987), the compulsive womanizer who combs the Upper West Side for candidates and justifies his behavior by saying, "I have a vested interest in meeting strangers. Every woman that I've ever liked or communed with or given great satisfaction to always started off as a stranger."

It's hard to tell if that's a compliment or a canny insult at this distance, but her account and Toback's quotes would have raised red flags for any woman at the time.

She notes how Toback held her by the shoulders in order to move her around the room, hit on women using his movies and told her "I do that 15 times a week. Well, OK, maybe 50 times a week. Forty girls and 10 guys."

She writes:

Ask anyone in the film industry about Toback, and his less discreet days of '70s excess as a gambler, partygoer and womanizer are sure to arise. His libido was so legendary that in 1989 Spy magazine published an eight-page foldout chart of his exploits called "The Pick-Up Artist's Guide to Picking Up Women."

But Toback never concealed his behavior; he flaunted it.

For those wanting to find the behavior, to those willing to or capable of reading between the lines, it was all there. But then again, it was not.

Throughout, Getches' writing takes Toback to task on some things, doesn't pick up the scent on others. I don't know if she was aware of his reputation with women or, indeed, specific instances or stories, but it's not relevant whether she did or didn't. This is a well-rounded profile of what seems to be a complicated, pugnacious artist. That's what the industry was looking for, that's what Getches was assigned to deliver and that's what we were all conditioned to see.

More to the point, the format for doing anything above and beyond hints or nods when it came to sexual harassment really wasn't there yet even just 15 years ago. That doesn't absolve anyone, but it helps explain why Toback was never outed as his was this weekend.

As well, up until quite recently, the attitudes with which older publications would approach these men were also informed by generations of editors who were happy to dismiss their trespasses as "boys being boys." That rockstars carried on coercive relationships with underage girls just proved they were naughty, not criminal. That movie stars harassed or assaulted women just confirmed that they were "ladies' men" or "womanizers" not serial abusers. Takedowns were reserved for weirdos like Michael Jackson. Rape, by celebrities at least, didn't really exist.

That general, society-wide attitude, as we are all well aware by now, was so strongly calcified, and so rarely challenged, over the years that it continues to inform modern behaviors, attitudes and, yes, media coverage even today.

The many men and women who bridled against these editorial constraints as they attempted to report what they knew weren't considered legitimate investigative journalists — they seen as were wide-eyed idealists who weren't playing the industry's game. Many internalized that criticism. Many suffered quietly. The silencing effect on reporting sex abuse was the same.

But it was more than that that stopped publications from acting on what they knew about serial abusers. Overall, the mainstream press did not — and often still does not — imagine it was its job to take down men with these histories until their alleged violations became truly and unavoidably public. So long as these allegations were whispers, collecting and presenting them was work for the police, for victims, for advocacy groups for biographers, for gossip rags, for Kenneth Anger, for somebody, anybody, else.

And, yet, with all this in mind, Toback still caught heat, often through platforms most journalists looked down on (though read salivating).

Founded in 2002 — the same year as Getches' article for Salon — Gawker very consciously hammered away at these walls, at these attitudes. It' not deals journalists and bloggers alike made didn't mean shit to Nick Denton, they were something worthy of attacking themselves. Sometimes it went too far — in a bid for complete disregard of celebrity friendliness, Denton would create a live-updated map of their comings and goings. Overall, though, the Gawker Effect, which would play out across many publications, was a needed rebuke to establishment celebrity journalism.

Being out in front of this effect had a price, of course. Gawker would itself disappear into bankruptcy after being sued for publishing a sex tape of Hulk Hogan who was backed in his civil complaint by site nemesis Peter Thiel.

So, why didn't the media pipe up about the worst of Toback earlier? Here's Gawker's Richard Lawson doing it in 2010. Here's his colleague Adrian Chen doing it the same day. Here's Rich Juzwiak doing it some more a couple of years later. Those aren't the only revealing stories Gawker published about Toback, and Gawker wasn't the only one publishing them. It was all there. And, still, it never managed to stick.

Here, Toback is indicted, tried and convicted in absentia as a "creep." Most women know what a "creep" is, what that really means. Most men, more than half of the readership, does not. The takeaway is that Toback is someone to be avoided, not a distinctly criminal, dangerous character.

Even as Gawker tried to tear Toback down, it didn't quite grasp the gravity of the situation, it never had the right words or the right approach. Why exactly were Lawson, Chen, Juzwiak and other similarly dedicated, gifted writers doing it then? A yawp at the establishment? An attempt at rough street justice for indistinct, not fully understood moral trespasses? Social justice? Clicks? Yes.

We were almost there yet, but not quite. It was Bill Cosby that put us over the line.

In 2015, New York magazine published a long, harrowing account of the dozens of women allegedly raped by the America’s Dad. Complete with their own words and, just as striking and unusual, their photographs, it was an application of the still-fresh "oral history" article format to a very serious legacy of very serious crimes. Other equally disturbing personal accusations of rape had surfaced online before, to be sure. But never had so many concerning one person been collected in one story delivered in a prestige format. It was front-page news told through an article that itself became front-page news.

With the massive moral and, yes, traffic success of that exposé, all other abusers would soon be on borrowed time. Stretching out beyond just criminality to include generalized stories of harassment, the format of the Cosby story has been applied to Bill O'Reilly, Harvey Weinstein, Amazon’s Roy Price and now Toback. We have the tools now.

More than that, we have the interest, the motivation and the license. Editors want these stories and, thanks to the lessons of Gawker's downfall, know better than ever how to publish them without getting sued into oblivion. Engaged writers see the tide is turning on the issue of sexual harassment as well. Lawyers, publicists, PR reps and more no longer have complete control of the firehose of information. Victims are emboldened by a media that is now more willing than ever to listen to, believe and print their stories. Perhaps more than anything else, everyone is just fucking tired of playing a game that helped see someone who himself may be a serial abuser become president.

Things are far, far from perfect now. But the ball has just begun slowly rolling in the right direction as statements and stories from every part of the culture are starting to show. As the process starts, more exposés will come and, eventually, the media will get this often right more than it gets it wrong (though that comes as only little recompense to actual victims).

Yes, the media has been talking about James Toback and, in a lesser way Harvey Weinstein this whole time. It was just never saying the right things.

Shares