Since allegations of former Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein’s abhorrent treatment of women have come to public light, we once again have an opportunity to talk about sexual harassment. These negative experiences are prevalent, pervasive and problematic for women in the workplace. And such ill treatment not only has a toxic impact on the female recipient, but has reverberating dysfunctional effects for employment settings as well.

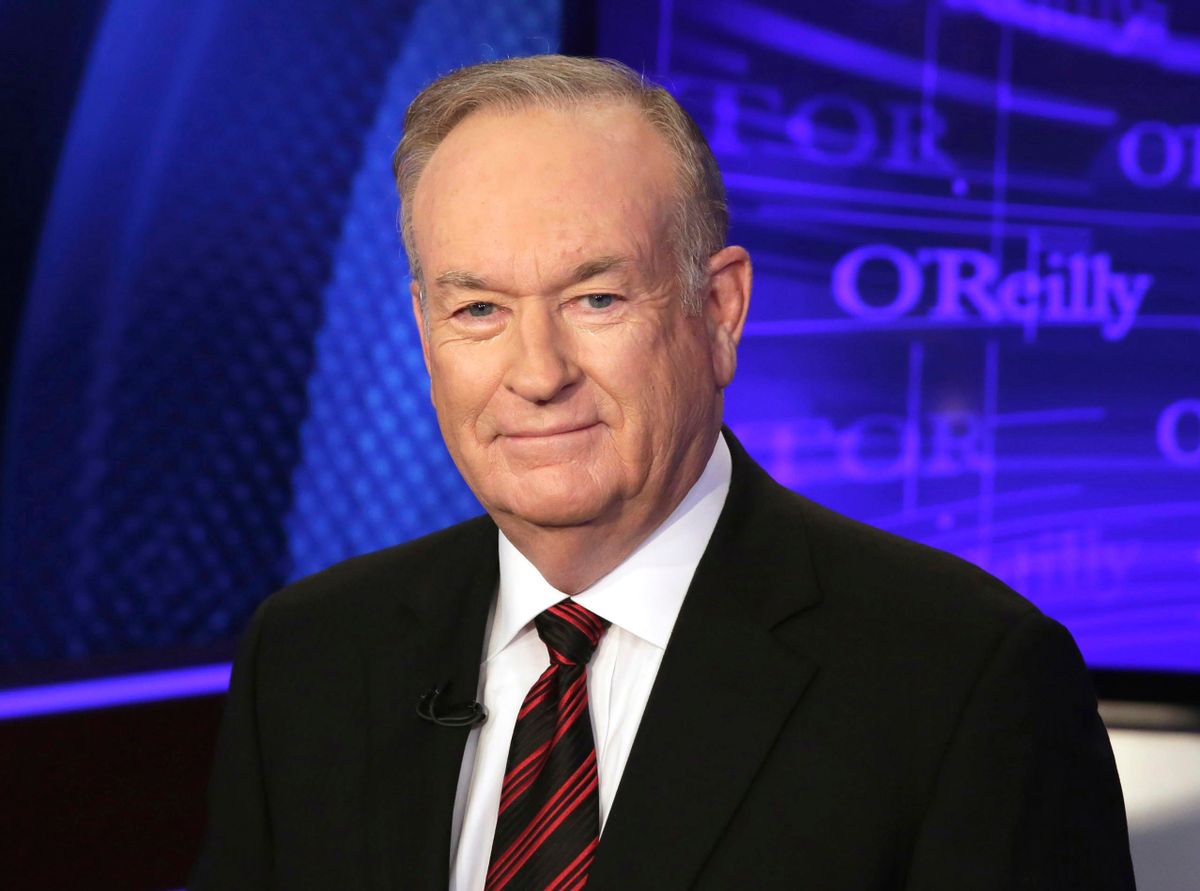

The past year we’ve also seen an increase in prominent women, including Gretchen Carlson and Megyn Kelly, coming forward to publicly speak about their experiences of harassment in the workplace. We’ve witnessed the fall from grace of big names, including Roger Ailes, Bill O’Reilly and Bill Cosby, and companies, including Uber. Rather than showing isolated incidents, these examples reflect workplace abuses that affect the everyday woman.

In a summary of workplace bullying, using 66 independent samples totaling together nearly 80,000 male and female employees, the effects were extensive and potentially long-lasting and included depression, anxiety and substance misuse. But workplace mistreatment of women is not just a woman problem. It’s an institutional and societal one.

As a trauma psychologist and a working woman, I’ve been deeply impacted by all of this news. But I’d also like to encourage us to broaden the conversation to include incivility, bullying and general harassment of women in the workplace as well as what we can do to prevent the behavior and the results of it.

Using the trauma lens to see effects

Six months ago, I decided I’d use my expertise in trauma psychology to try to write a book for a public audience on incivility, bullying and harassment of women in the workplace. I wanted to tell people about the psychological research on trauma, share in-depth interviews with real-world women, and weave in my own broad clinical and personal experiences in the workplace.

I wanted to take readers on a journey through the world of women’s exposure to a range of negative interpersonal experiences on the job, from instances of rude or discourteous acts to physical and sexual assault. I wanted to document the potentially harmful physical and psychological health effects of these experiences, and the impacts on day-to-day functioning as well as career advancement. I thought this might help move the dialogue forward and present tangible solutions to more effective coping with these issues.

When I told a handful of friends I was writing this book, they told a few friends. And women started coming out of the shadows. One woman I interviewed sent an email to her scientific colleagues, and geologists, oceanographers and meteorologists from all over the U.S. began emailing me and pouring out their experiences over the phone. One woman sent me a bunch of her documents for a Title IX sexual harassment complaint, and I almost openly wept with her over the phone.

More than 15 years after the event, she was still deeply rattled. She was heartbroken, not for herself, but because she was unable to come forward until now. She sobbed as she expressed her regret in not being able to “save others.” Straight from the heart and using a split-second clinical judgment, I told her she was a hero, and that regardless of the outcome of her legal complaint, she took the hardest path with honor, dignity, and tremendous courage.

So far, I’ve interviewed over 50 women from various socioeconomic backgrounds and races and ethnicities. These include women from white-collar occupations, such as a former Wall Street lawyer, orthopedic and breast cancer surgeons, primary care physicians, pediatricians, university professors, geologists, oceanographers, mechanical engineers and financial analysts as well as women from blue-collar occupations, such as secretaries, housekeepers, construction workers, firefighters and emergency medical technicians.

Quite a number of these women were ethnic or racial minorities, and I’m trying to faithfully show how they often experience a double or triple whammy piece of the misogyny pie.

These women shared their experiences of being condescended to, patronized, badgered, intimidated, not listened to, judged prematurely and harshly, treated rudely or propositioned. I’ve been documenting how these women struggled to make sense of these events, what they did to cope, and what they wished they had done differently.

Many told me of decreased morale and job satisfaction, of their stomach churning as they prepared to enter their place of employment. Many liked their jobs and didn’t want to lose them. They were afraid if they came forward, they might be labeled a troublemaker or fired. And why wouldn’t they be afraid when women are routinely disbelieved and commonly blamed? We generally do not complain or report offenses. We receive whatever incivility, bullying or harassment comes along. We ask ourselves: “What are my choices? Do I comply or resist? Do I report or be silent? Do I submit or risk being ostracized, demoted, fired or worse?”

And then too often we tell ourselves, “It is what it is.”

More stories pouring in

The stories continue to come in. Women I interviewed gave me the names of friends and family members who also had stories and had suffered consequences. One woman contacted her cousin, who had experienced bullying and obstruction in the whitewater rafting industry and since started her own company, teaching women to enjoy and master rafting. Even the medical transcriptionist from the company I hired to turn the audio files from my phone interviews into text contacted me. She said, “I hope it’s not inappropriate for me to reach out, but have I got stories for you!”

Women have few to no places to go to talk about these experiences. And they want reality checks and validation that they are not imagining these experiences. They need to know that they are not being overly sensitive, and that anyone with an ounce of integrity and a warm heart would be equally bothered by what they have gone through.

If now is not the time to have this conversation, I don’t know when is. Many women are rising up, whether through the Women’s March or other venues, to say, “This is so not OK.” And women are recently posting messages on social media with the hashtag #Metoo.

Moving forward

How I wish women could see themselves in the stories of other women, and experience an increase in empathy for themselves and others. I wish I could tell women to trust their instincts and accurately recognize, label and recover from workplace misogyny.

We must put in place workplace policies and procedures to lessen the occurrence of such treatment for women. The organizational or legislative actions taken thus far have been far from sufficient and will take years and a tremendous amount of effort and resources to achieve.

![]() So what can we do today? If we want to address incivility, bullying and harassment of women in the workplace, we must join together to prevent it from happening, call it out when it occurs and create a safe environment in which to heal. Workplace mistreatment of women is not only a great wrong; it makes us sick and is a waste of our valuable individual and collective talent.

So what can we do today? If we want to address incivility, bullying and harassment of women in the workplace, we must join together to prevent it from happening, call it out when it occurs and create a safe environment in which to heal. Workplace mistreatment of women is not only a great wrong; it makes us sick and is a waste of our valuable individual and collective talent.

Joan Cook, Associate Professor of Psychiatry, Yale University

Shares