In a great irony, the Republicans, who promised to eliminate the Affordable Care Act and roll back Medicaid expansions, are in essence about to do the reverse – at a huge cost to the U.S. Treasury. This year Obamacare will become what could be seen as an expanded version of Medicaid.

From my perspective as a finance professor and former insurer CEO, I predicted trouble when President Trump said last summer that he would let Obamacare fail. He didn’t say at the time that he’d help make sure that happens by driving up premiums – or that millions will rejoin the ranks of the uninsured while the federal government spends billions more in the process. Yet that almost certainly is in the cards now.

How could this be?

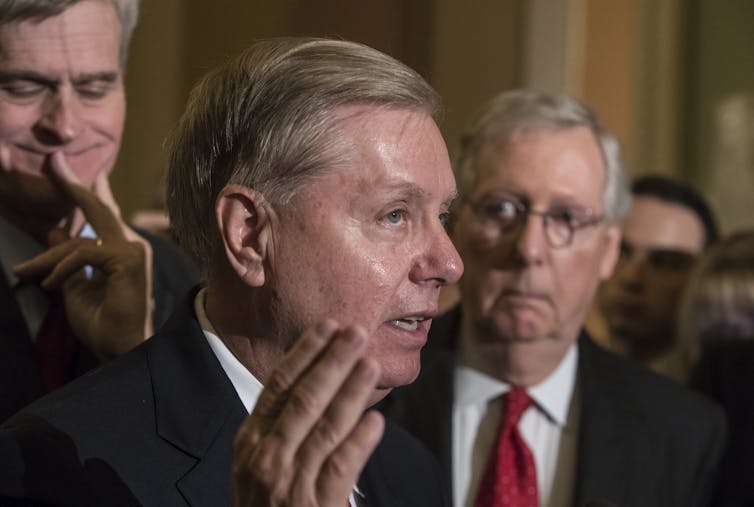

AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite

An ineffectual Congress unable to pass even minimal corrective legislation and bullying actions from the White House have produced an enormous increase in nominal premiums of at least 34 percent for 2018 plans offered on the individual exchanges. The increases came about as plans scrambled to cover the higher risk of expensive care. Meanwhile, large group premiums continue to grow at a little over 6 percent.

But not all marketplace consumers will pay for those increases – taxpayers will. The average subsidy for Obamacare consumers will grow by 45 percent, making the net premium costs even lower for many!

This anomalous result comes from the way that Obamacare subsidies are calculated. Subsidies are determined by taking the difference between stated premiums and a fixed percent of an enrollee’s income (2 percent for those just above the poverty level; up to 9.5 percent for at the top).

Premium prices rose this year not only because insurers left the marketplace. Insurers also had to incorporate losses caused by Pres. Trump’s suspension of cost-sharing subsidies into their premiums and uncertainty about who would enroll.

The president would want us to see the rising premiums as signs of the Obamacare “implosion” he predicted. But in reality, they are steps leading to a redefinition of the exchanges. Originally, sliding-scale subsidies based on income were to make access affordable for everyone. But sky-high premiums mean that only those qualifying for these subsidies are likely to purchase insurance on the exchanges, while others are priced out.

So Obamacare becomes an extended Medicaid expansion

This latest scenario looks a lot like the Republican plans for Medicaid under the waivers, as enacted by Indiana and planned widely in red states.

These Medicaid waiver programs for the poor require enrollees to pay some portion of premiums and cost of care to independent private insurers, just like the exchange plans do. But the level of eligibility for subsidized exchange plans goes far beyond Medicaid range for states that took the option to expand. These states cover enrollees up to 138 percent of the poverty level (US$16,623 for an individual) while the exchange plans subsidize coverage up to 400 percent of the poverty level ($48,240).

The typical conventional working-age Medicaid enrollee qualifies for care for less than nine months until he or she gets a job and loses coverage (kids and the elderly stay on far longer). These enrollees typically regain Medicaid coverage after a “spend down” period when they have a medical event that they can’t afford which eats up their cash or dumps them out of the job market.

Effectively, many of the same people rotate between conventional Medicaid and the Obamacare insurance exchange. Thanks to the subsidies under the ACA, these folks will not suffer the 34 percent increase in premiums and will stay with exchange plans. Since subsidies are rising, many of them may pay far less, or even zero premiums.

As over three-quarters of those on the exchange receive substantial subsidies, the enrollment on the exchanges will not drop precipitously although government outlays will jump.

Who loses?

However, the other quarter are out of luck. They will have to pay far more. Thanks to lax enforcement of the individual mandate to acquire health insurance or face tax penalties and President Trump’s executive order allowing lower-priced, stripped down, non-exchange options, these folks are almost certain to exit the exchanges.

So the bottom line is that most folks left in Obamacare will be those still receiving significant subsidies. These are the people who look a lot like conventional Medicaid enrollees – because they were enrolled before or are on the edge of eligibility now. Effectively, we have expanded the Medicaid program to them through the back door.

Unfortunately, this is a very expensive way to expand Medicaid.

There are two big losers. One is those individuals who relied on exchange plans but don’t receive subsidies. The other is the federal deficit. The former often are the near-elderly or those with preexisting conditions who couldn’t get coverage before at a reasonable rate. They are stuck with high premiums necessary to cover the extra risk induced by the chaos of repeal and replace efforts. The second are the taxpayers, who have to absorb the higher subsidies, amounting to over $7 billion.

The winners are certainly not the insurance companies, in spite of Mr. Trump’s statement that the subsidies are a “bailout” payment allowing them to “make a killing” on their ACA policies. In fact, almost all report significant losses on their exchange products, and many have left or failed financially. And even if they were to make windfall profits, the extra must be rebated to their customers under a little-reported provision of the ACA limiting the amount they can retain beyond direct medical costs.

Does anyone win?

The only winners here may be those low-income people who now have higher subsidies and a lower net cost of insurance. Virtually no one else comes out ahead – not insurers, not other individuals, not the government.

![]() If they knew this, even rock-ribbed conservatives might well join their liberal friends in opposing this incremental approach to health policy, even though the alternatives they favor would differ greatly.

If they knew this, even rock-ribbed conservatives might well join their liberal friends in opposing this incremental approach to health policy, even though the alternatives they favor would differ greatly.

J.B. Silvers, Professor of Health Finance, Weatherhead School of Management & School of Medicine, Case Western Reserve University

Shares