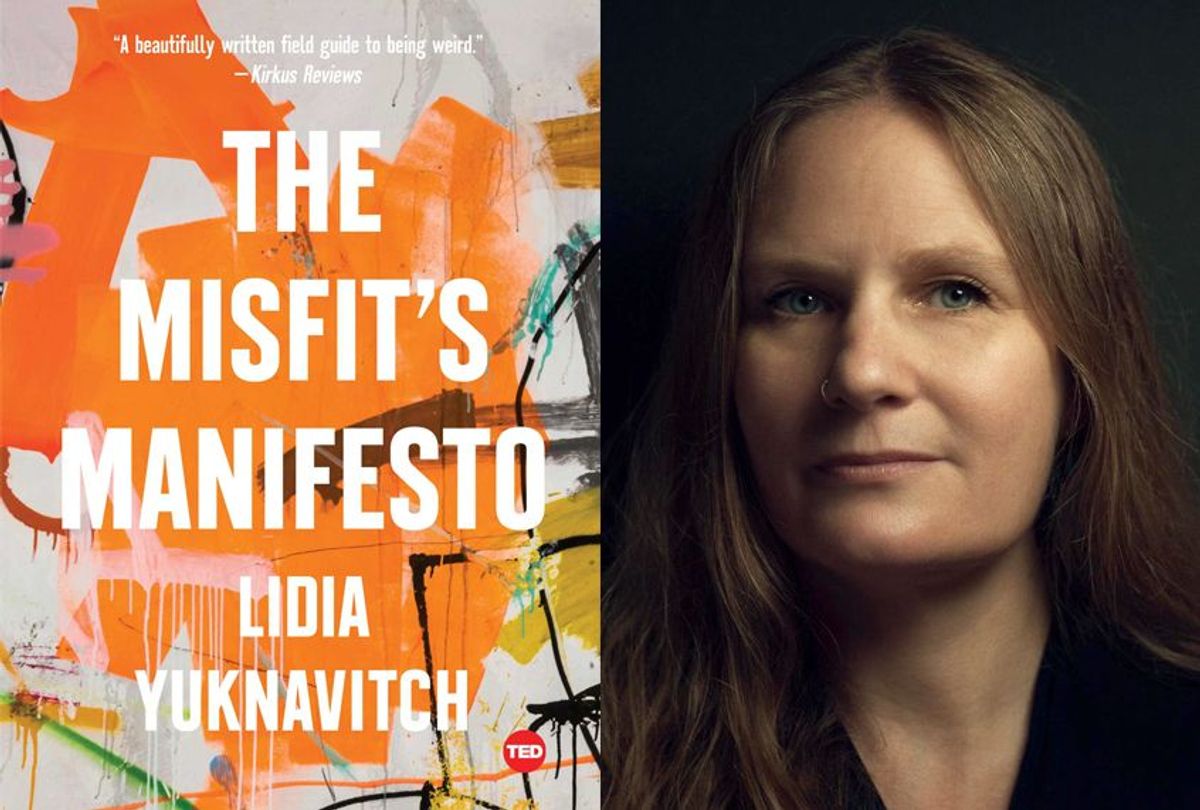

Lidia Yuknavitch is an unlikely motivational icon. As she's chronicled in her viral TED Talk and her previous works like "The Chronology of Water," she's spent much of her life on the outer edges. As she says in her newest book, "So yeah. I'm the kid who got hit in the face during dodgeball," the one who's faced grief and depression and not always in the most tidy, seemingly heroic ways. All of which makes her a world class expert on how and why outsiders can thrive, the person to write a book called "The Misfit's Manifesto." Part memoir, part guidebook, part testimony from fellow misfits, Yuknavitch's book is a beacon of hope for all who don't color within the lines.

Salon spoke to the author recently about the rewards of not fitting in.

For those who are less familiar with your work, why don’t you tell me what a misfit is?

In some ways, I think everyone on the planet has a little piece of misfit in them, because we don’t always feel like we belong. Everybody has hard days or hard years or whatever. The people I’m talking about have usually had some set of fracturing experiences in their life, either dramatic ones or grief ones, or they're veterans who have been to war or refugees or domestic violence victims. People who slipped out from figuring out how to find the path or an identity that felt stable. The more I talked to people after I did that TED Talk, I realized, “The thing is to get these stories out into the air in the hopes that we can find each other and feel less lonely and freakish."

How did the book evolve and change as you were writing it and witnessing what has been going on in our country?

There are a few sentences in the book where I couldn’t restrain myself from making an irate comment about different attitudes floating around just now in the era of Trump. While we were putting the stories together, it really was a collaborative effort. The focus changed a little bit too; we need to be finding ways to talk to each other rather than against each other. Collecting people who are ordinarily viewed as having issues or problems or some brokenness, and shining light on what we have to give to culture and how we can help other people talk to each other — that shifted the focus altogether.

One of the first things is you bust that myth of the nobility of suffering. It seems really important.

It is to me. I do understand the underpinnings of that idea, and I get that we all unconsciously believe that. When I started thinking about it, the actual suffering part is terrible.

We have this image about the suffering body, and you being closer to grace when you’re suffering. Anyone who’s suffering knows what you feel close to is dead. You don’t feel grace. The grace that comes later is the story we place over it. Even though I don’t have some magical answer about what suffering is or isn’t, I do know that there’s more than one story, and that if we multiply the stories, we can maybe feel less like we’re failing in our own suffering.

That also speaks to this idea of forced heroism.

Yes. I make a crappy hero. I’ve never achieved it. I’m often identifying with the villain character, or sometimes with the side characters who don’t really get to carry the sword or anything and feed the horses. That myth of the hero — I’m not trying to kill it or say it doesn’t exist. I’m just saying there are a variety of other storylines and other bodies out there that have never fit the hero’s journey. What if we sometimes tell those stories?

It does feel like a lot of the time we impose this idea that you go through a hard time and that’s where something wonderful actually happens. As opposed to, “Sometimes things just suck.”

It sucks for a long time. Some of us never achieved any kind of transcendent moment. Maybe no one does. Maybe everybody is just telling a fiction that it even exists.

Maybe I just want to interrupt the suffering story and put a little area in there for those of us who just aren’t buying that trajectory.

You’re also very clear that it doesn’t mean that you don’t find meaning in suffering.

I’m a lifelong swimmer, and so it’s been useful to think about sitting on the bottom of the ocean when the bad thing has taken your agency away. Once you’re down there, maybe there’s something useful you could bring back to the surface for those of us who are able to survive it at all. That’s a cool story. That’s helped me in my life. The stories other people tell in the book have helped them.

Tell me why it was important for you to talk about the creativity-misfit connection and the way that we find ourselves through the art that we create and through the art that we experience?

That’s a big deal for me. Pain or loss or grief or anger or suffering, they are what they are. There are also doors or windows or portals or opportunities that allow for self-expression. The main narratives we're given culturally ask you to take your pain and privatize it and then fit into the mono-story. What I’m finding, working with people all over, is that they're also the threshold where pure imagination can get born. It’s like creation is the other side of distraction. That’s the place I want to open up.

If you were going to advise someone who maybe feels really lost and is looking for that anchoring in creative expression, how would you tell them to start? I think many times when we’re most lost in life, we don’t even know how to begin.

I try not to advise anyone because the impression is you must follow my lead. I do think a couple of things occurred to me, like finding others like you. Hunting for tribe members or people who smell like you or do things like you so that you’re in a room with others and mercifully not alone all the time. But also trying to figure out how to help others. I know we always feel like we’re in a space of depletion when something too hard is happening. Weirdly, the opposite can be true if you’re helping another person. I don’t mean to sound Mother Teresa, because I also threw some shade at her.

But I do believe just the basic idea — not to save someone else, but just to help someone else even a tiny bit — can take you one step away from the ego of your suffering. That can be useful.

Then, the last thing I’d say is one of my darkest times [was] when I didn’t have a place to live, this wizened old woman friend of mine just gave me a painting canvas. It was a size of a wall of a bedroom, and she didn’t say anything about it. She just put it on her porch and put some paints up there. I had no idea that that would draw me or that I would find an actual space to play out what I was doing on the inside. What I ended up doing was painting this sort of raging crazy looking abstract. It was so big. It was bigger than me. I was putting an expression out that was bigger than me and didn’t have to look like anything. I’m going to remember that day the rest of my life, because someone put the opportunity for self-expression in front of me, which is why I think we need more art in the schools, not less art in the schools.

Where do we go from here? Lidia, I think 80 percent of the time I just feel incredible despair and fear. Then the other 20 percent of the time, I look at my kids, as I’m sure you look at your son, and I feel hopeful. I can see movement in the direction of visibility, of diversity, of accepting diversity as the norm in a lot of places and accepting different kinds of people. It feels like the loudest people are the most terrible. That doesn’t mean that they’re the most people.

That’s right. I feel all those things you’re talking about. Every day, I feel them hourly. I feel them. You wake up and you look at the news; you’re like, “Goddamn it!”

I guess I’m more and more convinced that — not that it’s the answer but it’s a piece of some things that will help — is for us to be always sharing stories and never let what’s happening culturally silence us. We really do know how to be a part of each other and understand each other more together than apart. We really do know how to understand difference. The only way through is together and with each other. My little tiny piece is sharing stories and sharing art as a language for how to stay connected.

This interview has been condensed and lightly edited for clarity.

Shares