Nevada has temporarily called off its first inmate execution in 11 years. Scott Dozier, sentenced for the 2002 murder of his 22-year-old drug associate, Jeremiah Miller, was to be put to death on Nov. 14. Dozier instructed his lawyer in August not to file any more appeals.

On Thursday, Nov. 9, however, Judge Jennifer Togliatti temporarily postponed the execution. Judge Togliatti said she was “loath to stop” Dozier’s execution, but she did so because she was concerned about the untested and controversial drug protocol that would be used to put him to death. She wanted to give the state Supreme Court a chance to evaluate.

From my perspective as a scholar of capital punishment, Nevada’s new drug protocol sheds a glaring light on the troubled state of lethal injections in the United States. It also raises some serious ethical questions.

Lethal injection’s crisis

The first lethal injection protocol was developed by Oklahoma’s medical examiner, Jay Chapman, in the late 1970s. Back then, Oklahoma was looking for an alternative to electrocution, which was considered inhuman and brutal.

The protocol Chapman developed called for the use of three drugs: The first, sodium thiopental, would anesthetize inmates and put them to sleep before the lethal drugs were administered. The second drug, pancuronium bromide, a muscle relaxant, was meant to render the inmate unable to show pain. The third drug, potassium chloride, led to a cardiac arrest and eventual death. This protocol soon became the standard and was adopted by all death penalty states — now numbering at 31.

However, by the start of this decade, pharmaceutical companies, “citing either moral or business reasons,” refused to allow their products to be used in executions.

The difficulty of securing the drugs that had been part of the standard protocol led death penalty states to experiment with many different drugs in many different combinations.

States likes Alabama and Arkansas, for example, maintained the three-drug protocol but replaced sodium thiopental in the standard drug cocktail with midazolam or pentobarbital, which doctors normally use as sedatives or for anesthesia. Other states, including Arizona and Ohio, started using a two-drug protocol, while a few, such as Georgia, Missouri and South Dakota, adopted a single drug.

Nevada’s new protocol involves a three-drug combination — the sedative diazepam (better known as Valium), the muscle relaxant and paralytic cisatracurium and the opioid fentanyl.

My research on methods of execution reveals that this combination of drugs has never been used in an execution.

What is the problem with this?

Execution by a lethal injection, even when it follows the standard protocol, is a surprisingly complicated procedure. Finding usable veins and getting the drug dosages right has proved to be particularly difficult. As I found out, it has often been an unreliable method of execution. Since its introduction, 7 percent of all lethal injections have been botched.

Those complications and difficulties increase when states try out new, untested drugs or drug combinations. Convicts have taken a leading role in opposing such experimentation. In February 2017, a death row inmate in Alabama appealed to the United States Supreme Court saying that he preferred death by firing squad to an injection of midazolam. While it recognized lethal injection’s history of problems, the majority held that since Alabama did not offer the firing squad as an execution method, his preference could not be honored. In a dissenting view, however, Justice Sonya Sotomayor called the use of new drugs in lethal injection the “most cruel experiment yet.”

Nevada’s Dozier too has said that he is opposed to “the state’s plan to kill him using a drug protocol that has never been used in an execution.”

There are other troubling issues as well. Using fentanyl, a drug that is killing thousands of Americans annually during the current opioid crisis, is horrifying, to say the least.

In addition, figuring out the right dosage of diazepam and fentanyl in Nevada’s new protocol will not be easy. And if this is not done correctly, Dozier could even wake up in the middle of the execution, as Susi Vassallo, a New York University professor of emergency medicine, has written on lethal injection notes. In the words of Judge Togliatti, he could be “aware of pain” and struggle to breathe.

Employing the powerful paralytic cisatracurium in this new drug protocol raises other ethical concerns.

If the combination of diazepam and fentanyl fails to work, cisatracurium will prevent Dozier from signaling to his executioners that they are botching the execution even as it happens. As David Waisel, an anesthesiologist at Boston Children’s Hospital, claimed, “Cisatracurium can hide signs of inadequate anesthesia.” That is its only purpose.

In other lethal injection protocols, the muscle relaxant was also designed to stop the heart. Thus, those who conduct the execution and those who witness it will not be able to see the visible signs of Dozier’s suffering if it occurs.

Do citizens have a duty?

In my view, if Nevada and other death penalty states insist on experimenting with new drugs to keep the machinery of death running, citizens and government officials alike need to take responsibility to prevent any cruelty.

Writing about the use of the guillotine in France more than half a century ago, Albert Camus, philosopher, author and journalist, said,

“Society must display the executioner’s hands on each occasion, and require the most squeamish citizens to look at them, as well as those who, directly or remotely, have supported the work of those hands from the first.”

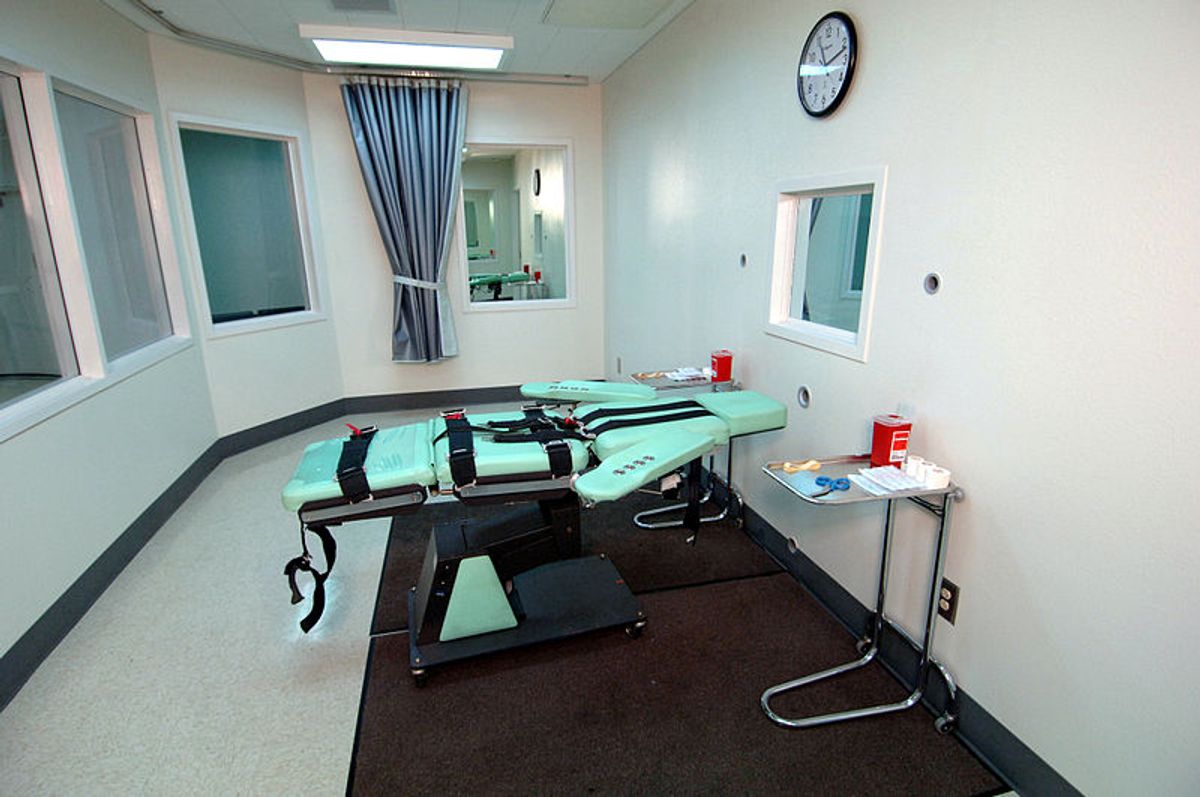

![]() While lethal injection is different from the guillotine, in modern times the imperative remains the same.

While lethal injection is different from the guillotine, in modern times the imperative remains the same.

Austin Sarat, Professor of Jurisprudence and Political Science, Amherst College

Shares