Considering the history of television news a few years ago, iconic anchor Ted Koppel declared that CBS’ 1968 debut of “60 Minutes” forever altered the landscape of broadcast journalism: A news program drew enough advertising to turn a profit. As Koppel told it, “60 Minutes” showed broadcasters that news divisions could make money — which was a huge shift in how management executives thought of news, affecting both the quality and type of coverage broadcast over the publicly owned airwaves.

Until then, broadcast news in the U.S. had been a costly requirement media companies had to bear as part of getting permission to use the airwaves. “All of a sudden, making money became part of what we did,” Koppel told the audience of a “Frontline” series called “News War.”

In the decades since, news divisions have been held to the same profit-making standards as corporate media’s entertainment divisions. Corporate owners slashed foreign bureaus as coverage remained focused on emotion and celebrity rather than public affairs.

In late October 2017, the Federal Communications Commission made it even easier for media conglomerates to focus on money-making. That was when the FCC abolished a World War II-era policy that was intended to force news broadcasters to be connected to — and accountable to — the communities their programming reached. My work as a political economist suggests that local broadcast media content is about to get worse, focusing even more on stories that can turn a profit for corporate headquarters rather than serving local communities. And the big companies that operate these stations are going to withdraw even farther from the communities they cover, threatening a key foundation of American democracy.

Connecting with communities

The longstanding requirement, known as the “main studio rule,” said television and radio broadcasters had to have local studios, where viewers or listeners could interact with and communicate with the people who were putting their news on the air. This was part of fulfilling the broadcasters’ explicit obligation to use the airwaves to benefit society: As the Radio Act of 1927 put it, they had to operate in the “public interest, convenience and necessity.”

That would help keep news decisions about schools, zoning, health, environment, emergencies and local issues connected to the community. It also helped encourage broadcasters to employ people who lived in the areas their signals reached.

In the decades since, the media landscape and technology both have changed dramatically. The FCC still assumes that broadcasters are local media because it issues station licenses in specific community areas. Yet the holders of those licenses are usually large conglomerates with centralized news operations sending homogenized programming out across the nation.

Advocates for eliminating the main studio rule — including the National Association of Broadcasters — note that most audience communications with media companies are online. They say that makes having a local physical office less important than it may once have been. Among the supporters of this view is FCC Chairman Ajit Pai, who was appointed to the commission by Barack Obama in 2012 and tapped to head it by Donald Trump shortly after his inauguration.

Pai also raises another common argument against the main studio rule: its cost. In October he wrote that the policy change will reduce burdens on media companies and let them improve audience service accordingly: “eliminating this rule will enable broadcasters to focus more resources on local programming, newsgathering, community outreach, equipment upgrades, and attracting talent — all of which will better serve their communities.”

The two Democratic members of the five-member FCC, Mignon Clyburn and Jessica Rosenworcel, dissented from their Republican colleagues’ decision, objecting to the effects the ruling would have on local news. Clyburn wrote that the FCC’s change “signals that it no longer believes, those awarded a license to use the public airwaves, should have a local presence in their community.” Rosenworcel, for her part, wrote in a separate dissent: “I do not believe it will lead to more jobs. I do believe it will hollow out the unique role broadcasters play in local communities.”

History has heard this argument before.

Promises of deregulation

As the lesson of “60 Minutes” spread in the late 1970s and 1980s, news organizations and their corporate parent companies enjoyed massive windfalls, broadcasting content that was cheap to produce: It focused on thin happy banter between anchors rather than substantive hard-hitting reporting. At the same time, media conglomerates including Time Inc., NBC owner General Electric and Comcast began heavily lobbying Congress and regulatory agencies like the FCC to roll back decades of media policies meant to help foster educational and informational needs of citizens in a democracy.

They found success when President Bill Clinton signed the sweeping Telecommunications Act of 1996. Then-FCC chairman Reed Hundt declared that with the act, “We are fostering innovation and competition in radio.” He said the new law would increase diversity in both ownership of broadcast stations and the viewpoints they present. And he said it would create a space for more competition in the telecommunications marketplace that would, ultimately, benefit consumers.

But nine years later, a report from Washington, D.C.-based watchdog group Common Cause determined “the public got more media concentration, less diversity, and higher prices.” Cable and phone rates didn’t drop from competition, but skyrocketed with consolidation. Industry leaders’ promises to add 1.5 million jobs turned into layoffs of more than 500,000 people. And Hundt himself 10 years later trumpeted not the improvements of service to the public, but rather the financial rewards reaped by corporations and their shareholders.

So now, more than 20 years after the act’s passage, fewer corporations than before control a larger share of radio, broadcast and cable television in the United States. Many of those corporations have financial stakes in online media, too, meaning their reach and ideologies extend far beyond just television and the AM/FM dial.

The FCC’s decision to roll back the main studio rule is yet another in a long line of policymaking and regulatory decisions that will further boost corporate media, not citizens.

A pathway into the future

By eliminating the main studio rule, the FCC has severed one of the last remaining ties between broadcasters and local communities. (Others, including rules about media companies’ consolidation, are on the chopping block.) The body charged with ensuring media companies serve the public interest has opened the door even wider to treating news as a profit-motivated medium operated to benefit shareholders, rather than as a key element of American civic life.

Even before the FCC undid the main studio rule, the effects of the Telecommunications Act made local news more homogeneous and less diverse. This is particularly harmful for rural America, where just two-thirds of residents have regular broadband access at home — and only limited data services on their mobile smartphones. That means millions of Americans without regular internet access are relying on broadcast television as their sole form of entertainment and information about their communities.

The real question for citizens is simple: Did deregulation work? Is the quality of broadcast news better today than it was 20 years ago? Will it improve if companies’ legal and regulatory requirements are loosened?

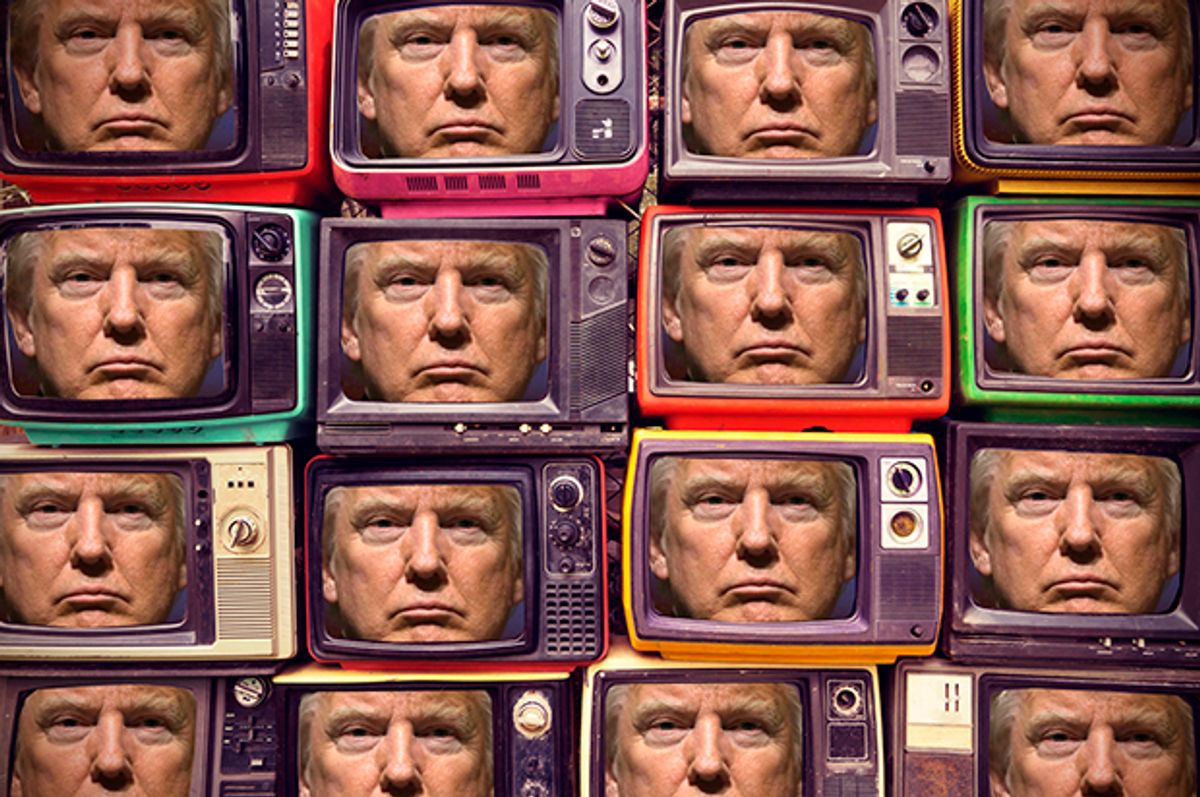

![]() All Americans know the answer. And so does the FCC.

All Americans know the answer. And so does the FCC.

Margot Susca, Professorial Lecturer, American University School of Communication

Shares