When he published “The Sun Also Rises” in 1926, Ernest Hemingway was well-known among the expatriate literati of Paris and to cosmopolitan literary circles in New York and Chicago. But it was “A Farewell to Arms,” published in October 1929, that made him a celebrity.

With this newfound fame, Hemingway learned, came fan mail. Lots of it. And he wasn’t really sure how to deal with the attention.

At the Hemingway Letters Project, I’ve had the privilege of working with Hemingway’s approximately 6,000 outgoing letters. The latest edition, “The Letters of Ernest Hemingway, Volume 4 (1929-1931)” – edited by Sandra Spanier and Miriam B. Mandel — brings to light 430 annotated letters, 85 percent of which will be published for the first time. They offer a glimpse at how Hemingway handled his growing celebrity, shedding new light on the author’s influences and his relationships with other writers.

Mutual admiration

The success of “A Farewell to Arms” surprised even Hemingway’s own publisher. Robert W. Trogdon, a Hemingway scholar and member of the Letters Project’s editorial team, traces the author’s relationship with Scribner’s and notes that while it ordered an initial printing of over 31,000 copies – six times as many as the first printing of “The Sun Also Rises” — the publisher still underestimated the demand for the book.

Additional print runs brought the total edition to over 101,000 copies before the year was out — and that was after the devastating 1929 stock market crash.

In response to the many fan letters he received, Hemingway was typically gracious. Sometimes he offered writerly advice, and even went so far as to send — upon request and at his own expense — several of his books to a prisoner at St. Quentin.

At the same time, writing to novelist Hugh Walpole in December 1929, Hemingway lamented the amount of effort — and postage — required to answer all those letters:

“When ‘The Sun Also Rises’ came out there were only letters from a few old ladies who wanted to make a home for me and said my disability would be no drawback and drunks who claimed we had met places. ‘Men Without Women’ brought no letters at all. What are you supposed to do when you really start to get letters?”

Among the fan mail he received was a letter from David Garnett, an English novelist from a literary family with connections to the Bloomsbury Group, a network of writers, artists and intellectuals that included Virginia Woolf.

Though we don’t have Garnett’s letter to Hemingway, Garnett appears to have predicted, rightly, that “A Farewell to Arms” would be more than a fleeting success.

“I hope to god what you say about the book will be true,” Hemingway replies, “though how we are to know whether they last I don’t know — But anyway you were fine to say it would.”

He then goes on to praise Garnett’s 1925 novel, “The Sailor’s Return”:

“…all I did was to go around wishing to god I could have written it. It is still the only book I would like to have written of all the books since our father’s and mother’s times.” (Garnett was seven years older than Hemingway; Hemingway greatly admired the translations of Dostoyevsky and Tolstoy by Constance Garnett, David’s mother.)

An overlooked influence

Hemingway’s response to Garnett — written the same day as his letter to Walpole — is notable for several reasons.

First, it complicates the popular portrait of Hemingway as an antagonist to other writers.

It’s a reputation that’s not entirely undeserved — after all, one of Hemingway’s earliest publications was a tribute to Joseph Conrad in which Hemingway expressed a desire to run T.S. Eliot through a sausage grinder. “The Torrents of Spring” (1926), his first published novel, was a parody of his own mentors, Sherwood Anderson and Gertrude Stein and “all the rest of the pretensious [sic] faking bastards,” as he put it in a 1925 letter to Ezra Pound.

But in the letter to Garnett we see another side of Hemingway: an avid reader overcome with boyish excitement.

“You have meant very much to me as a writer,” he declares, “and now that you have written me that letter I should feel very fine — But instead all that happens is I don’t believe it.”

The letter also suggests that Garnett has been overlooked as one of Hemingway’s influences.

It’s easy to see why Hemingway liked “The Sailor’s Return” (so well, it appears, that he checked it out from Sylvia Beach’s Shakespeare & Co. lending library and never returned it).

A reviewer for the New York Herald Tribune praised Garnett’s “simple but extremely lucid English” and his “power of making fiction appear to be fact,” qualities that are the hallmark of Hemingway’s own distinctive style. The book also has a certain understated wit — as do “The Sun Also Rises” and “A Farewell to Arms.”

Garnett’s book would have appealed to Hemingway on a personal level as well. Though it’s set entirely in England, the portrait of Africa that exists in the background is the same sort of exotic wilderness that captured the imagination of Hemingway the boy and that Hemingway the young man still longed explore.

Imagining Africa

But Hemingway’s praise of Garnett leads to other, unsettling questions.

From its frontispiece to its devastating conclusion, Garnett’s book relies on racial stereotypes of an exoticized, infantilized Other. Its main character, an African woman, brought to England by her white husband, is meant to command the reader’s sympathy — indeed, the choice she makes in the end, to send her mixed-race child back to his African family, hearkens to an earlier era of sentimental literature and decries the parochial prejudices of English society.

However, that message is drowned out by the narrator’s assumptions about inherent differences between the races. Garnett’s biographer Sarah Knights suggests that Garnett was “neither susceptible to casual racism nor prone to imperialist arrogance,” yet Garnett’s 1933 introduction to the Cape edition of Hemingway’s “The Torrents of Spring” claims “it is the privilege of civilized town-dwellers to sentimentalize primitive peoples.” In “The Torrents of Spring,” Hemingway mocked the primitivism of Sherwood Anderson (cringe-worthy even by 1925 standards), but as Garnett’s comment indicates, Hemingway imitated Anderson’s reliance on racial stereotypes as much as he criticized it.

What, then, can we glean about Hemingway’s views on race from his exuberant praise of “The Sailor’s Return”? Hemingway had a lifelong fascination with Africa, and his letters show that in 1929 he was already making plans for an African safari. He would take the trip in 1933 and publish his nonfiction memoir, “Green Hills of Africa,” in 1935. The work is experimental and modernistic, but the local people are secondary to Hemingway’s descriptions of “country.”

Late in life, however, Hemingway’s views on Africa would shift, and his second safari, in 1953-4, brought what scholar of American literature and African diaspora studies Nghana tamu Lewis describes as “a crisis of consciousness” that “engendered a new commitment to understanding African peoples’ struggles against oppression as part, rather than in isolation, of changing ecological conditions.”

But back in 1929, when Hemingway was wondering what to do with an ever-growing pile of mail, that trip — along with another world war, a Nobel Prize and the debilitating effects of his strenuous life — were part of an unknowable future.

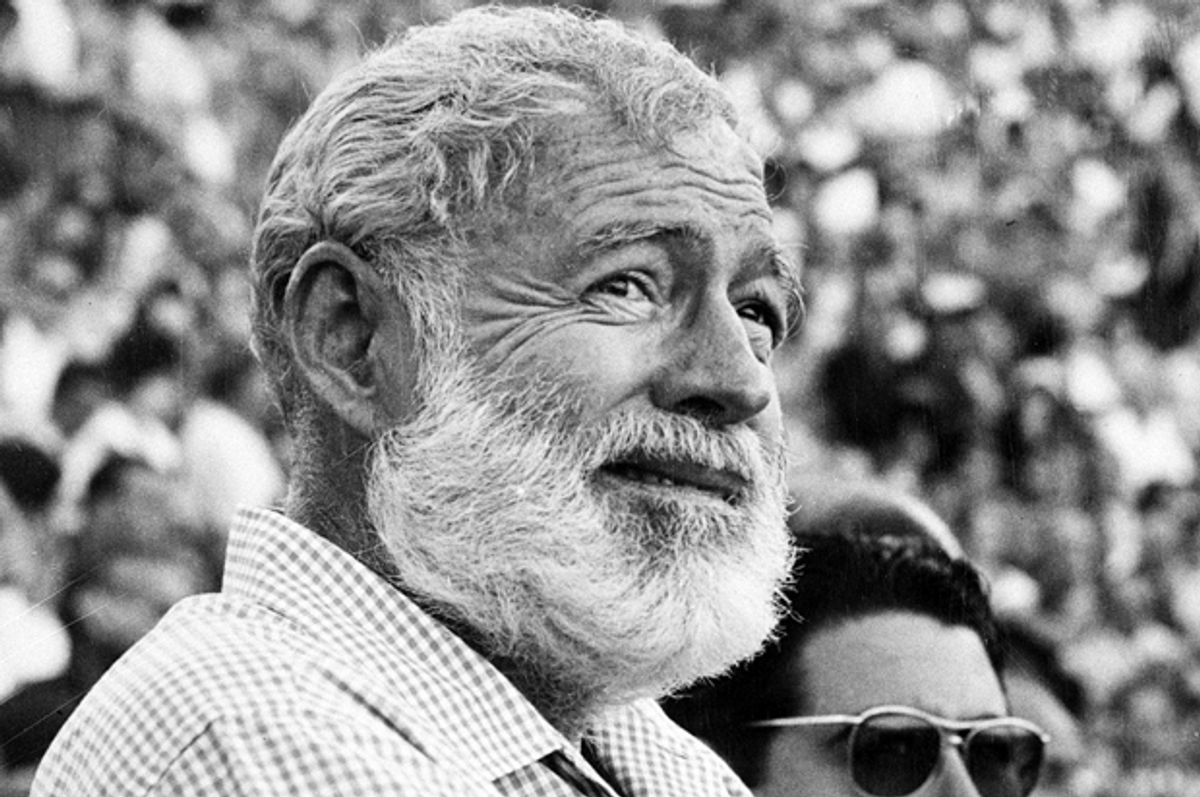

![]() In “The Letters 1929-1931” we see a younger Hemingway, his social conscience yet to mature, trying to figure out his new role as professional author and celebrity.

In “The Letters 1929-1931” we see a younger Hemingway, his social conscience yet to mature, trying to figure out his new role as professional author and celebrity.

Verna Kale, Associate Editor, The Letters of Ernest Hemingway and Assistant Research Professor of English, Pennsylvania State University

Shares