So, I just watched “The Lost Tapes: Patty Hearst,” a new documentary which debuted last night on the Smithsonian Channel as part of the network’s Lost Tapes franchise. In its promotional material, the producers promised to air images and audio recordings that had not been seen or heard by the general public since the 1970s. Presumably, this is to shed new light into the dramatic story behind the Hearst kidnapping.

Does it succeed in doing this? Yes, to such a degree that it sets the standard by which all future attempts to depict the ’70s era irresponsible super-rich must be judged.

It makes sense that this particular topic continues to fascinate us. The 1970s was a decade of tremendous political upheaval — you had the Vietnam War, Watergate, the energy crisis, economic stagflation — and, like our own time, it was one in which the rich seemed to get away with everything. Within the past decade or so, we’ve seen Wall Street bankers torpedo the economy and leave taxpayers holding the bag, a con artist like Donald Trump get caught lying over and over again (including most recently denying that he boasted about committing sexual assault) while still being elected president and powerful men from all walks of life successfully cover up their sex crimes.

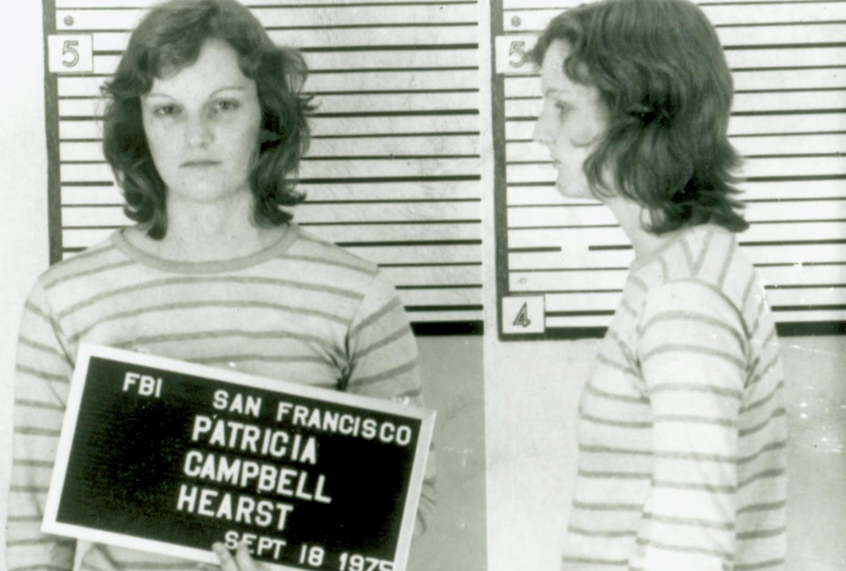

By these standards, the offenses of heiress Patricia Hearst seem almost tame by comparison. After being kidnapped by a radical left-wing terrorist group called the Symbionese Liberation Army, Hearst soon became a passionate member of the group, sharing in their cause and denouncing her family, fiance and former way of life. In a streamlined and efficient way, the new Smithsonian documentary lays out the chain of events from Hearst’s kidnapping through her trial, conviction, commutation and eventual pardon. The documentary devotes particular detail to showcasing the tapes she left for authorities that demonstrated the extent of her indoctrination.

Of course, unlike the vast majority of individuals in the Rich People Who Get Away With Awful Things canon, Hearst does have a plausible argument for her own victimhood. Because she started out as a kidnapping victim, it is entirely possible that her conversion to far left-wing politics was as much the result of Stockholm Syndrome as a genuine shift in her belief system — indeed, perhaps even more so. Wisely, the Smithsonian documentary touches on these possibilities without trying to definitely answer these questions on its own.

To be fair, I don’t think the Patty Hearst case is being revisited because of new information. If I had to guess, I would say that Americans are regaining an interest in a number of 1970s-era crimes because so many of them played out the class and racial tensions that have risen to the fore in our own decade.

This was the case even before Charles Manson’s death, although the timing there was eerily apropos, considering the current zeitgeist. It explains why there are not one but two projects in the works about the kidnapping of John Paul Getty III — the upcoming Ridley Scott film “All the Money in the World” and the Danny Boyle television series “Trust.” On that occasion, the kidnapping had much less idealistic motives; Getty’s kidnappers straight up demanded ransom money for the heir’s safe return.

Nevertheless, there was still an intrinsic fascination in seeing the super-rich dragged down to everyone else’s level. The same, no doubt, inspired the fascination with Manson, which was revived earlier this year when initial reports came out that he was having medical issues. Based on the man’s infamy, you would think that his notorious Manson Family had killed hundreds. Yet Manson himself was only found guilty of either murdering or conspiring to murder seven people — but seven rich and famous people, most notably the rising star Sharon Tate. Had Manson committed his heinous crimes against ordinary civilians, it is highly questionable whether he would have become a cult figure today.

Which brings us back to the latest Hearst documentary. It’s a story that hinges around understanding the mind of an heiress who, ultimately, feels more like a pawn in other people’s games than an active player of her own. Without Hearst’s wealth — which, it must be emphasized, she did not earn on her own — her tale would have been long ago forgotten, with Hearst herself rotting away in a jail cell for crimes that she indisputably committed and for which she was rightfully convicted.

The mere fact that we’re still following her story, and treating her experience as if it’s something special, reveals that the super-rich managed to “win” here, even if one of their own did experience a harrowing ordeal for more than a year. Even then, the fame that came with her name gave her a cushion when her dramatic tale was over — yes, she served several months in prison, but her sentence was soon commuted by President Jimmy Carter, and eventually she was outright pardoned by President Bill Clinton.

If “The Lost Tapes: Patty Hearst” had made the extra effort to shed light into the mind of the kidnapped heiress, it could have informed what is otherwise a lame, if hardwired, obsession with the rich and famous in American culture. As it is, this narrative is just one more in a series of sensational stories that criticizes our class system but which, by virtue of their very existence, also celebrates it.