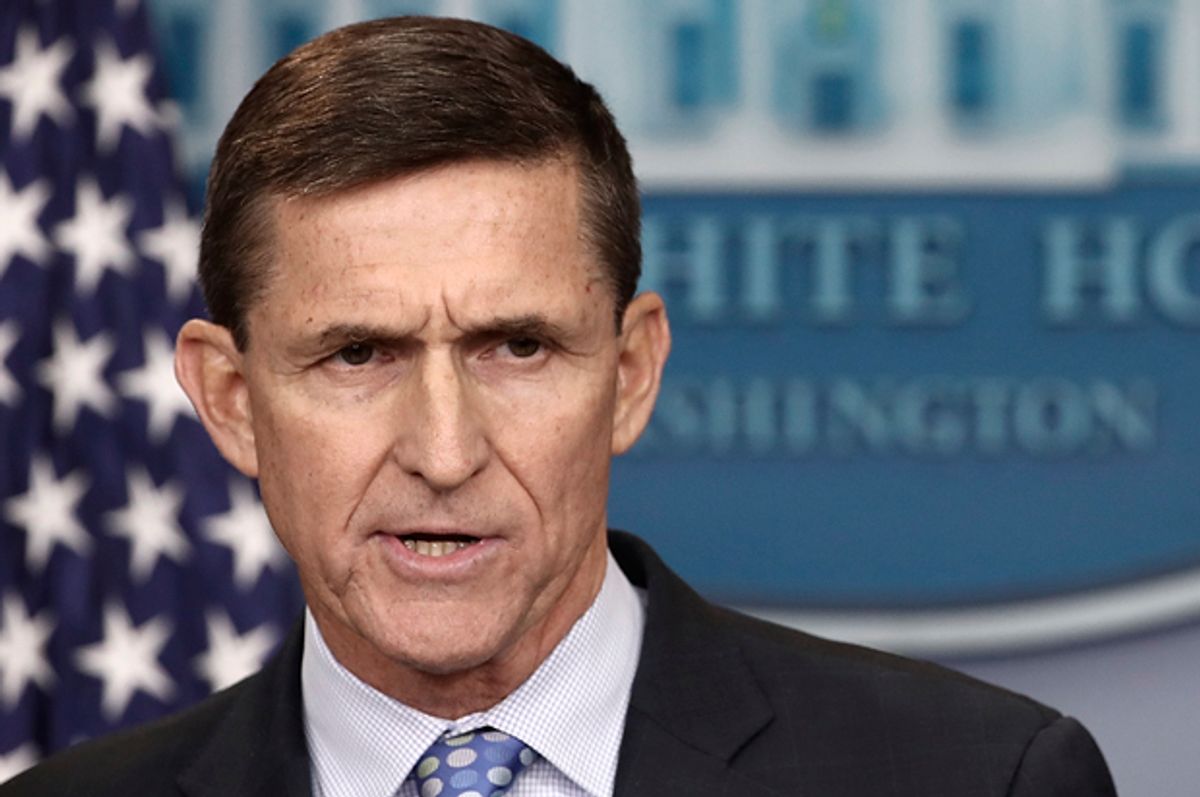

When he started investigating General Michael T. Flynn, Special Counsel Robert Mueller concentrated on his income and undisclosed contacts with Russian officials. Now, however, Mueller’s investigation has broadened to include Flynn’s business with Turkey. Flynn faces possible fraud and money-laundering charges for failing to disclose a payment of $530,000 from the Turkish government. (The Foreign Agent Registration Act, FARA, requires disclosure of work for foreign governments, including details about compensation.) Flynn could also face conspiracy and kidnapping charges for allegedly negotiating a payment of $15 million to deliver to Turkey Fethullah Gülen, an Islamic cleric and political foe of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. Gülen has lived in exile in the United States since 1999; he was granted permanent residence in 2008. The Turkish government accuses him of orchestrating the coup attempt in July 2016 and imprisoned thousands of his followers.

If indicted on these charges, Flynn could end up in jail for a long time. (Lawyers for Flynn have denied the kidnapping allegations, which were first reported by The Wall Street Journal.) Alternatively, Flynn and his son, Michael Flynn Jr., who works with him at the Flynn Intel Group, a lobbying firm in Virginia, can avoid jail time by becoming cooperating witnesses in Mueller’s investigation. Flynn was an integral part of the Trump campaign and briefly served the Trump administration as national security adviser. If the Trump campaign colluded with Russians — for example, to coordinate the release of hacked emails embarrassing to Hillary Clinton and a social media campaign to influence voters — Flynn would probably know. Mueller has already brought charges against Trump’s former campaign manager, Paul Manafort, his associate Rick Gates, and a campaign foreign policy adviser, George Papadoupoulos. Flynn may be next.

Flynn has a history of cutting corners and breaking rules. Flynn failed to disclose income from three Russian companies, including a 2016 speaking fee of $45,000 from RT, an official propaganda arm of the Kremlin. He failed to disclose contact with Russia’s ambassador to the United States, Sergey Kislyak, to FBI investigators conducting a background check to renew Flynn’s security clearance. Intercepts of Flynn’s phone calls with Kislyak reportedly showed that Flynn discussed sanctions on Russia and suggested the possibility of sanctions relief once Trump became president. Flynn also failed to disclose his involvement in a $100 billion nuclear energy deal, which he explored during an undisclosed trip to Israel and Egypt in 2015.

Flynn’s work for the Turkish government is also under investigation. The Flynn Intel Group was paid $530,000 by Inovo BV, a thinly capitalized Dutch company that serves as a front for Inovo Turkije, whose principal, Ekim Alptekin, is a close associate of President Erdoğan. Public records in the Netherlands confirmed that Inovo BV is a shell company. Flynn should have known that Inovo BV was a pass-through and, given Alptekin’s close relationship with Erdoğan, that Inovo BV’s funds originated from the Turkish government. Flynn hid the origins of the money and the fact that his payment was funneled through a third party. When details of the contract surfaced in press reports, Flynn acknowledged his service for the Turkish government by belatedly registering under FARA.

The contract with Inovo BV required Flynn to lobby on appropriations bills for the departments of State and Defense. Flynn’s duties also included keeping his client informed about “the transition between President Obama and President-Elect Trump.” In effect, Flynn was also hired to conduct a smear campaign of Gülen. In an article published by Flynn in The Hill on election day, November 8, 2016, Flynn referred to Gülen as a “shady Islamic mullah residing in Pennsylvania.” He wrote: “To professionals in the intelligence community, the stamp of terror is all over Mullah Gülen’s statements . . . Washington is hoodwinked by this masked source of terror and instability nestled comfortably in our own backyard.” Flynn endorsed Turkey’s demand for extradition. “The forces of radical Islam derive their ideology from radical clerics like Gülen, who is running a scam. We should not provide him safe haven.”

Flynn was apparently willing to consider more drastic action. James Woolsey, a former director of the CIA, attended a meeting with Flynn in September 2016 during which Flynn discussed abducting Gülen and delivering him to Turkish authorities at the Imrali Island Prison off the coast of Turkey. The meeting was also attended by Berat Albayrak, Erdoğan’s son-in-law, and Turkey’s foreign minister, Mevlut Cavusoglu. Woolsey described the proposed extradition outside of the US legal system as “a covert step in the dead of night to whisk this guy away.” He and Flynn were both working for the Trump campaign at the time.

Earlier this month, The Wall Street Journal reported that Flynn and his son rejoined discussions about Gülen at a meeting in December in New York at the 21 Club, where Flynn was offered as much as $15 million to deliver Gülen. The Turkish government denies that this meeting took place; Flynn’s lawyers also called the Journal report false. If the story is true, however, Flynn and his son could be prosecuted under the RICO law (Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations).

Despite Flynn’s pattern of illegal and unethical behavior, President Trump took extraordinary steps to protect him. On February 14, 2017, Trump met with the then-FBI director, James Comey, in the Oval Office. “I hope you can let this go,” said Trump, alluding to Comey’s investigation of Flynn. Comey took it as an order, but did not comply. Trump fired Comey on May 9.

Trump had already fired, in March, Preet Bharara, the US Attorney for the Southern District of New York. Among the cases Bharara was pursuing was the prosecution of Reza Zarrab, a gold trader and Erdoğan crony charged with violating US sanctions on Iran. According to the indictment published shortly after Bharara was fired, Zarrab’s economic crimes involve illicit gold sales on behalf of the Iranian government, which were deposited into Turkey’s HalkBank; the proceeds helped support Iran’s nuclear program and business enterprises linked to the Iranian Revolutionary Guards Corps. Mehmet Hakan Attila, a Halkbank executive, was also arrested, on charges of conspiring with Zarrab to evade US sanctions against Iran.

It is not unusual for an incoming president to replace US attorneys. But the manner and timing of Bharara’s dismissal raised red flags. Trump acted improperly toward Bharara, initiating direct contact by calling Bharara three times. Bharara, who had jurisdiction to investigate suspected criminal conduct in business in New York, rightly refused to take the calls. Bharara believes that Trump would have asked him “to do something inappropriate,” had they spoken. Trump removed Bharara after having assured him in November 2016 that he would retain his job. Turkey has invested heavily in efforts to influence the US government, spending millions of dollars annually to hire former members of Congress as lobbyists, sponsoring junkets for members of Congress in the Turkey Caucus, and making large contributions to think-tanks such as the Atlantic Council. Was Turkey’s influence a factor in Trump’s decision to fire Bharara?

Erdoğan appears intensely interested in the Zarrab case, repeatedly asking US officials to drop the charges against him. An FBI source told me that the allegations against Zarrab include selling a ton of gold each week and taking a 15 percent commission. A superseding indictment filed by prosecutors in September charges that Zarrab conspired with senior Turkish government officials, including Erdoğan’s then-minister of the economy, in a scheme to dodge US sanctions on Iran that involved “laundering funds in connection with those illegal transactions, including millions of dollars in bribe payments.”

Zarrab hired Michael Mukasey, an attorney general in the George W. Bush administration, and Rudy Giuliani, a former Republican mayor of New York City and a notorious hard-liner on Iran, in March. According to Zarrab’s attorney, Benjamin Brafman, Giuliani and Mukasey were not hired to participate in Zarrab’s legal defense team; they were paid instead “to explore a potential disposition of the criminal charges”—in other words, to get the case closed down by influencing senior US government officials. That means, in effect, going over the head of prosecutors and bypassing the normal plea bargain channels—thereby undermining the administration of justice. Greenberg Traurig, Giuliani’s firm, is a registered agent for the Turkish government. Both Giuliani and Mukasey, who acted as advisers to the Trump campaign, appear to be cashing in on their connections to the White House.

The Zarrab case is a further example of Turkish efforts to circumvent the US legal system, but lobbying to get the charges dropped in the case has become a fool’s errand. Reports suggest that Zarrab recently agreed to act as a cooperating witness. Judicial interference, however, is part of an established pattern of conduct by Turkey, which has also become adept at buying influence in Washington. Turkey has many reasons for its largesse: it wants to deflect attention from its support to Syrian jihadis, official corruption, the killing of Kurds, and the systematic arrest of opponents under the guise of fighting terrorism.

The United States needs leadership that is steely-eyed toward Turkey as well as toward Russia. Yet Turkey’s influence-buying efforts are paying off. The Trump administration ignores Erdoğan’s human rights abuses and election irregularities. The White House turned a blind eye when Erdoğan’s security guards beat up US citizens outside the Turkish ambassador’s D.C. residence in May. The Trump administration was virtually silent when Turkey bought S-400 anti-aircraft missiles from Russia for $2.6 billion. Trump calls Erdoğan “a friend of mine” and praises his job performance, saying: “He’s getting very high marks.” Trump has his own interests to think about — stakes in major real-estate developments in Istanbul, as well as in a luxury furniture company in Turkey.

Trump’s disparaging of the US justice system undermines judicial independence. He has already issued a controversial pardon for Sheriff Joe Arpaio, who was convicted of disobeying a federal judge’s order. Knowing there is a potential presidential pardon in the works could dissuade Flynn from telling the truth as a cooperating witness. Efforts to subvert our democracy — by enemies foreign and domestic — may succeed unless the rule of law is fully and effectively applied in the case of Michael Flynn.

David Phillips is director of the program on peace-building and rights at Columbia University’s Institute for the Study of Human Rights. He served as a senior adviser to the State Department during the Clinton, Bush and Obama administrations.

Shares