These days renowned poet and cultural critic Kevin Young is one of the most reviled and dismissed of figures: He’s a learned expert on fakery. The author of “Bunk: The Rise of Hoaxes, Humbug, Plagiarists, Phonies, Post-Facts, and Fake News” began the book six years ago, long before “fake news” became a depressingly common pejorative. But at the time, Donald Trump was well into his insistent perpetuation of the “birther” lie questioning the legitimacy of then-President Barack Obama’s birth certificate — a story concocted out of thin air that attracted millions of believers.

“I do think there's a certain savviness to be able to recognize the way people want a good story, and I think that we underestimate that,” Young told Salon in a recent interview. “And what I call the narrative crisis of the past few decades is something that politicians have really capitalized on. You see it now all the time.

“For me, the focus is not measured by what someone intends, but by its harm and by the way that it affects us,” he added. “However you feel politically, the kind of discourse is such that it is filled with these divisions.”

To say “Bunk” feels more necessary and relevant this week would be to completely disregard the events of the week prior, and the week before that. Any given week, really, stretching back to Nov. 9, 2016. This interview was conducted within days of the Washington Post's catching an operative from James O’Keefe’s Project Veritas attempting to insert a false story into the publication. The foiled con was intended to discredit the extensive reporting the Post has published about women coming forward to accuse Alabama Senate candidate Roy Moore of child molestation.

Days before that, Trump asked Americans to doubt their own eyes and ears by trying to deny his appearance in the famous “Access Hollywood” recording that appeared in October 2016, in which he uttered the words “grab ‘em by the pussy.”

Young had a mountain of material to work with from before all of that, evidenced in the fact that the annotations for “Bunk” required nearly 100 pages of the book. But our current battle for reality and truth strikes him as more troubling than the sideshow hoaxes of the past.

“If we think of how fake news is used, just as a term, it kind of has this double meaning,” Young said. “On the one hand, fake news is actually something that's happened. There are stories being pushed out, whether it's ‘Pizzagate’ or the ‘bots who infiltrated the last election and pushed out fake, targeted information. That's a real thing that happened, and a troubling one. At the same time fake news becomes, and Trump employs it this way, an epithet used against news one doesn't like. Both are troubling in their own way.”

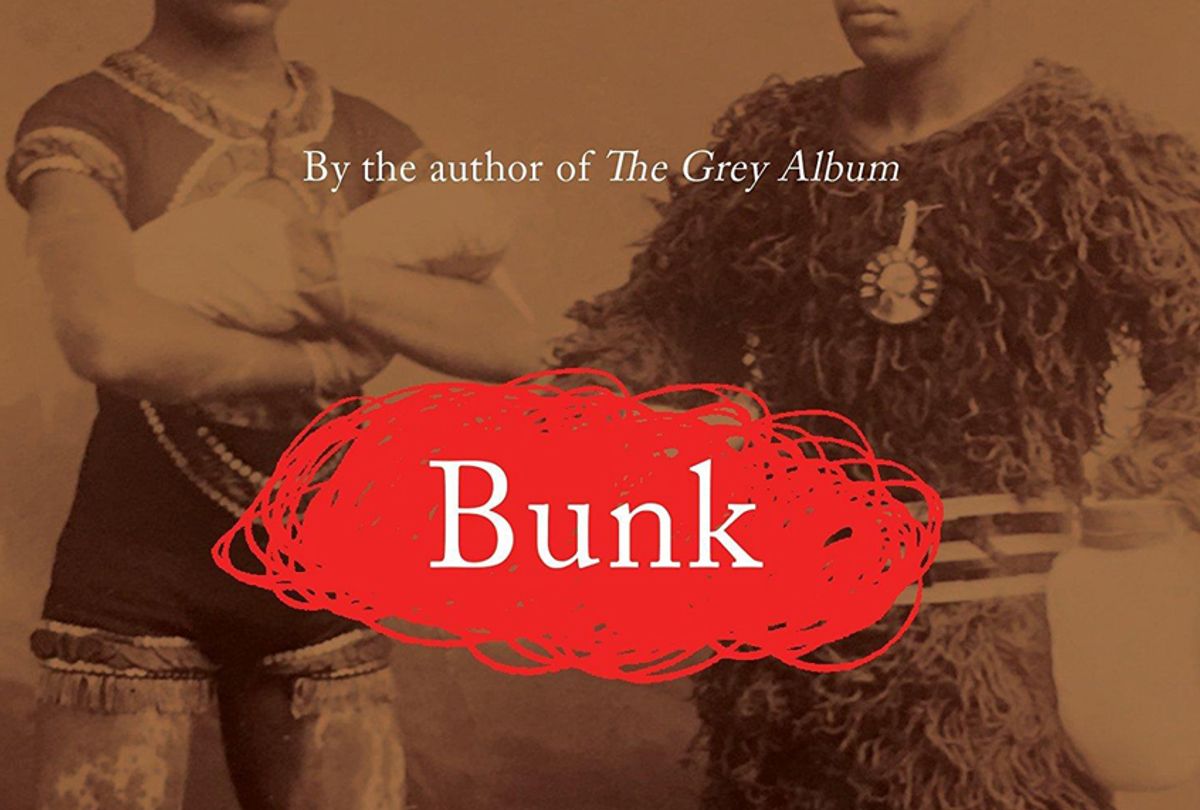

The fact that “Bunk” consists of 576 pages, including 20 photographs from traveling sideshow exhibits, illustrations of supposed societies living on the moon and other assorted fraudulent hokum, should tell you just how much fakery is part of our shared history.

But if not for the accelerated rate of information dispersal in the modern age, the book would have been shorter by around 70 pages. “I thought I’d nearly finished this book — filled with hoaxers and impostors, plagiarists and phonies,” he writes near the opening of chapter 19, “but as soon as I had sent a draft to my publisher, elated and relieved, Rachel Dolezal raised up her faux-nappy head. Now I have to take time to write about her too?”

Young is primarily known as a poet and his first major work of nonfiction prose, 2012’s “The Grey Album: On the Blackness of Blackness,” joined a body of work that includes 10 books of poetry. In addition to his role as poetry editor of the New Yorker, he’s also the director of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

“Bunk” represents the culmination of Young’s fascination with story, history and culture, and it is without question a poetic take on a difficult, fraught topic. The book’s density is in its language as well as its breadth, as Young engages with the mind-reeling nature of the subject matter by lyrically connecting irrefutable fact to astounding fictions, illustrating many times over the power hoaxing has to defy logic and reason.

“Poets often are dealing with history and are thinking about the way history moves across us, and we move in it,” Young explained. “Certainly the poets I love do that in different ways. Even the idea of an epic, Ezra Pound's definition of an epic is a poem containing history.

“I'm not a historian,” Young continued. “I know historians. I've worked with them. They have a really powerful way of looking at the world, and I think so do poets. And we have a way, I think, of making connections and thinking about them. I think it is a poet's book. I hate to say that, but I do think it has those kinds of leaps and connections that I think, I find in good poetry.

Dolezal, unfortunately for Young, is a stanza that snugly fit into the epic he’d already built; she’s a tremendous example of what Young describes as the hoax’s ability to “plagiarize pain.”

In “Bunk,” Young traces the current bamboozlement effectuated by the flimflam artists on Capitol Hill and in the White House back to P.T. Barnum and one of his earliest greatest shows, an act starring a black woman named Joice Heth. In 1835, Barnum claimed Heth, who may have been his slave, was George Washington’s nursemaid. This would have made Heth more than 161 years old.

The act was as wildly popular as the penny press’s perpetuation of a hoax that convinced the public that a scientist (who wasn’t actually a scientist and, indeed, did not truly exist) had viewed fantastic creatures living on the surface of the moon.

All of this is captured in the first chapter of “Bunk,” titled “The Age of Imposture.” Through the many pages following, Young traces our culture’s embrace of hoaxing from the past through the present, from sideshows through spiritualism, from the earliest works of science fiction through fabricated tales masquerading as journalistic pieces and memoirs revealed to be pure fiction.

“When I started, I thought these things would be true six years ago, and then they came more and more true in our current era, in a sense,” he said. “And the more I've gone around and thought about it, the more the analogies between what was happening in 1835 with Barnum, and the Moon Hoax or blackface, which was invented then, and I've never heard anyone try to connect blackface to this hoax tradition. And pseudoscience, too. All those things were happening almost literally to the year in the mid-1830s.”

Not only does he name many of the fakers who made headlines for making up stories — Lance Armstrong, Ruth Shalit, Jayson Blair, James Frey, the gang’s all here! — he calls back to a depressing refrain about the basis for fakeouts past, present and likely future. All of them are based in our country’s obsession and fear about race and racial stratification. Indeed, Young also explores the way that the very concept of race and the categorizations that are with us to this day are completely made up.

“It's not an accident that the [social media] bots from the last election were racialized or fake radicals, fake black groups,” he said. “All this kind of stuff, I’m sad to say, is very much in the tradition of the hoax.”

Barnum’s presence hovers throughout the book like a specter until “Bunk” arrives at its conclusion — “The Age of Euphemism,” the post-fact world we’re living in now. Days before Trump’s inauguration, he points out in “Bunk,” the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey circus shut down forever.

“The elephant in the room,” he writes, “is that what people say they want, and what they are willing to pay for, are often at odds.”

Now there's some cold hard truth in a post-truth age.

Shares