What can those armed with facts – like scientists, professionals and knowledgeable citizens – do to shape policy?

In April, scientists and their supporters took to the streets. The March for Science was a public defense of science as an invaluable part of society and policy. We, as academic scientists, were among them. When everyone returned to their labs and offices, we saw our fellow marchers search for ways to build on the momentum.

One of the most accessible options to do so is the federal public comment process.

What is public comment?

Public comment subjects federal policies to peer review. Scientists and other professionals can use public comment to ensure that policy is based on the best available evidence, vetting the science behind regulations.

When Congress passes a law, it provides a framework for federal agencies on how to implement it. Figuring out the details of implementation is usually up to the agency by making rules and regulations. Since 1946, the Administrative Procedures Act has required that each new rule be subject to public comment, giving citizens the chance to comment on and change the proposed rule before it becomes legally enforceable. Proposed and final rules are all published in the Federal Register, a publicly accessible online government database.

The act also ensures that agencies cannot ignore these comments by requiring the agency to respond to all “material” comments. This qualifier is critical. For an agency to respond to the comment, it must be unique and fact-based, such that it could “require a change in [the] proposed rule.”

Public Comments Project

You may have already encountered a public comment if anyone has asked you to submit a prewritten letter regarding a proposed rule. These “form letters” are written by organizations – often nonprofits – and then a copy is signed and submitted by a large number of people. While agencies may note the impressive response a proposed regulation triggers, these form letters are legally considered a single material comment.

Yet form letters often make up a large percentage of comments received. For example, in 2004, the EPA was in the process of making a rule that would reduce emissions of mercury from coal-fired utility units. The majority of comments on this proposed rule submitted through MoveOn.org were duplicates of the same two-sentence form letter or slight variants of a broad claim about the inadequacy of the proposed rule. This meant that the EPA received little real information to which it had to respond.

Form letters are popular because they are easier than writing a unique, fact-based comment. But scientists and other professionals often have the knowledge required to do so. They are trained to read and summarize evidence from a variety of sources. They are also familiar with the general principles of subject fields like ecology, economics or nutrition, which are recurring themes across many regulations.

Federal agencies need the expert information that scientists and professionals can provide. An analysis by the U.S. Forest Service found that the majority of public input was value-based. While these comments provided agency employees with critical information on public opinion, value-based comments were not as helpful to the planning staff as detailed comments that provided technical feedback. Only 9 percent of the comments sampled were classified as having a high level of detail.

Why should scientists engage?

Public comment allows for flexibility. With an online submission portal, it doesn’t require participants to be in a certain place to have input. Its consistency across federal agencies avoids the need to reacquaint oneself with agency-specific processes. Perhaps most importantly, it allows for public participation, opening the process to scientists and professionals across sectors and career stages without a personal contact or advisory position at the agency.

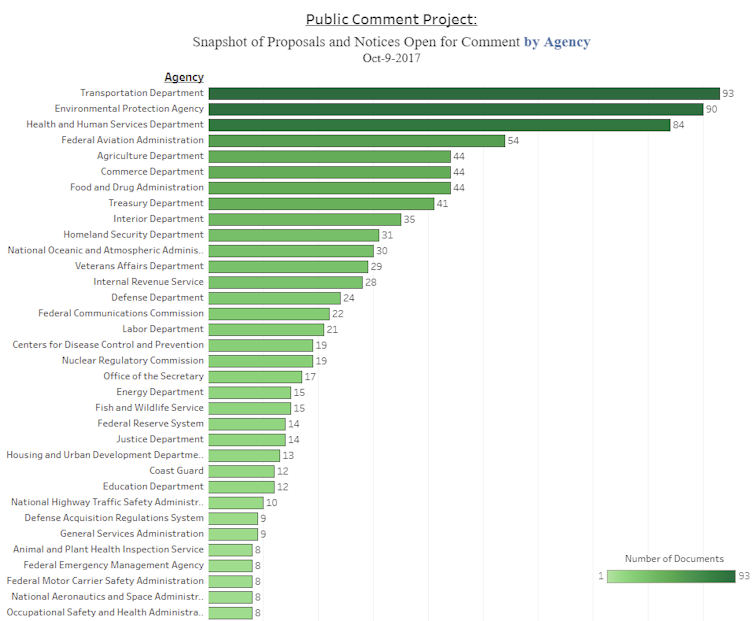

This isn’t to say that there are no barriers. For example, proposed regulations are often filled with jargon and organized in unclear ways. But there are sources designed to coach you through the process, including Regulations.gov. Material specifically oriented toward helping scientists and other professionals is available through the Public Comment Project, a website that we created with other colleagues and maintain. It includes how-to guides and helps you find rules of interest that are open for comment.

Has it made a difference?

Changes to rules as a result of public comment happen often. For example, in a 2016 proposed rule by the Centers for Medicare Medicaid Services, the agencies expanded the definition of “patient” in the final rule. The expansion was in response to comments by the Midwest Health Initiative and the American Hospital Association, among others. This effectively changed the scope of data that could be extracted for providers, suppliers, hospital associations and medical societies.

Or, take a National Marine Fisheries Service proposed rule to designate critical habitat for a marine snail, the black abalone. A comment written by one of us expanded the critical habitat designation so that all life stages of the species would be covered.

A formal analysis on a 1992 Environmental Protection Agency proposed rule on certain cancer-causing pesticides found that the agency was was more likely to bar the use of a particular cancer-causing pesticide when faced with evidence of high risk to human health or the environment. Public comment by environmental advocacy groups increased the probability of cancellation.

Why comment now?

Experts, from scientists to professionals, have an increasingly important role to quality-check the research that makes its way into policy – see, for example, this statement by the American Association for the Advancement of Science, one of the world’s largest scientific societies. Although the devaluation of science in public policy is a long-term issue, it has recently escalated rapidly. A few of the most recent examples include the removal of climate change-related data and research from government websites, proposed reduction in federal budgets for science including the complete removal of certain programs like NOAA’s Sea Grant, and the request of agencies for scientists to censor their language.

![]() Responding to a call for public comment is one way to check the facts that make up public policy. We call all scientists, professionals and knowledgeable members of the public to apply their specific expertise to this process.

Responding to a call for public comment is one way to check the facts that make up public policy. We call all scientists, professionals and knowledgeable members of the public to apply their specific expertise to this process.

Mary Fisher, M.S. Student, Aquatic and Fishery Sciences, University of Washington; Natalie Lowell, Ph.D. Candidate in Fisheries Science, University of Washington; Ryan Kelly, Assistant Professor, Marine and Environmental Affairs, University of Washington, and Samuel May, Graduate Student in Fisheries Science, University of Washington

Shares