Just how big a spy was Klaus Fuchs? Fuchs was arrested and jailed in Britain in 1950 for passing secrets about atomic research to the Soviet Union. At the time, Fleet Street claimed that he was a traitor who had sold the secrets of the atom bomb to the Russians. But as the initial storm of hysteria passed on to other crises and other spies, hard facts about the Fuchs case seemed elusive, despite investigation by writers more serious and authoritative than journalists in the popular press. The well-known author Rebecca West wrote a lengthy exposé of Fuchs’s treachery in "The Meaning of Treason." Two years after the trial a book about the “atom spies,” "The Traitors" by Alan Moorehead, was published and it turned out that the author had been selected and provided with enormous help by the British Security Service, MI5. Then a few years later the eminent historian Margaret Gowing turned her attention to Fuchs as a small part of her exhaustive volumes on the history of Britain’s nuclear program.

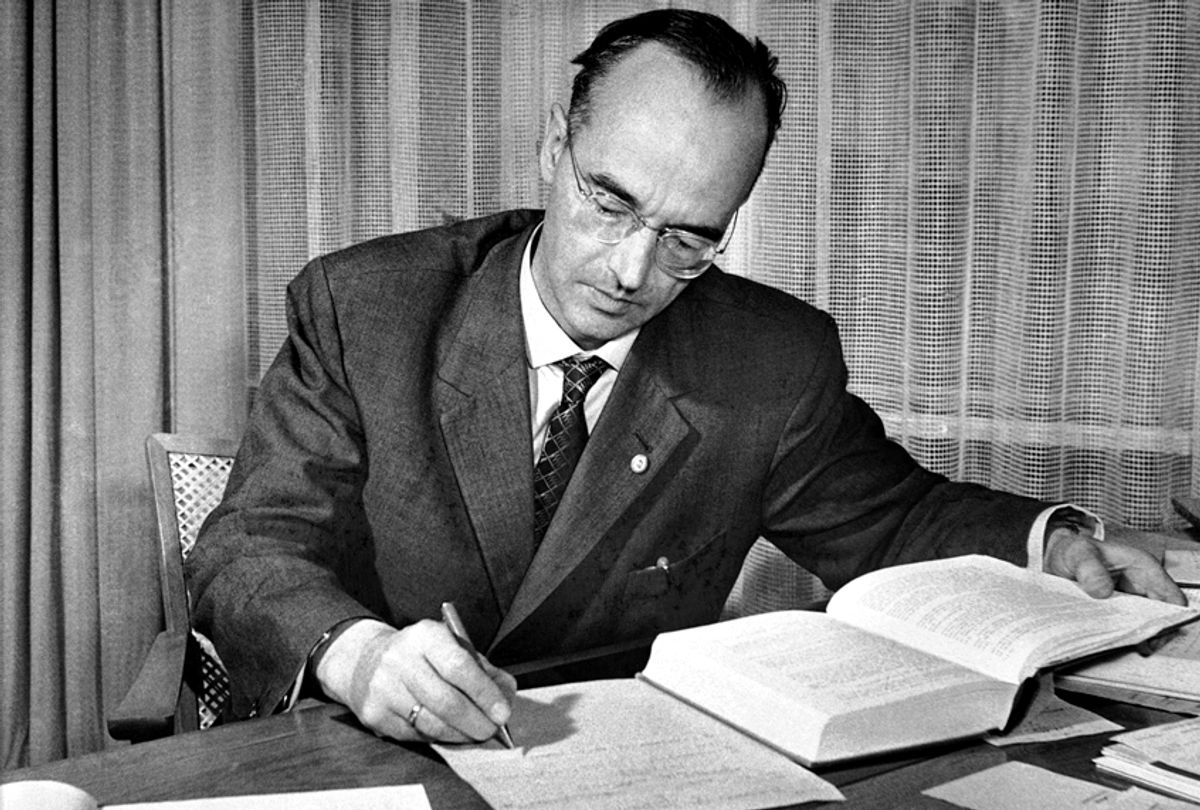

Despite all this work, facts seemed thin on the ground. True, Fuchs was a German scientist who had been a refugee from Nazi Germany, he had worked on atomic research, and his sentence of fourteen years’ imprisonment had been based on his own confession. The rest seemed contradictory. Was he, as the official history of Britain’s nuclear programme implies, a second-rate scientist merely handing over the work of others? Did he have any secrets to sell? Some academics suggested that the Russians would have built their bomb anyway, whether Fuchs had given them a few pointers or not. What sort of a person was he? Was he an evil conspirator or a slightly repressed man, naïve, divorced from reality, who gradually came to see the error of his ways? Was it true, as the MI5-sponsored book claimed, that their chief interrogator, William “Jim” Skardon, skillfully probed the psychology of Fuchs and persuaded him to confess?

I thought that I would get to the bottom of some of these questions several years ago, when I went to Moscow to inter-view someone who was intimately connected to Fuchs’s work as an atomic scientist. My appointment was with Academician Georgi Flerov, a man who had played a significant role in the first Soviet atomic bomb. It was Flerov who had written a letter to the Soviet chiefs of staff in 1942 suggesting that a nuclear weapon was possible, that it was likely that scientists in the United States, Britain and Germany were already working on this question, and that the Soviet Union should start its own programme urgently.

Flerov had later travelled to Berlin, in May 1945, shortly after the defeat of Nazi Germany, dressed in the uniform of a colonel in the NKGB,1 the Soviet State Security organization. He was hunting for German scientists who had worked 1 Soviet intelligence changed its organization and its name several times over the period covered by this book. To avoid complications and unnec-essary sets of initials, I will call them the OGPU before 1934 and the NKGB after that date. Soviet Military Intelligence, the GRU, was and remained a separate organization on the Nazi atomic programme during the war and arranging for them to go to the Soviet Union. It was not an easy invitation to refuse. Later, he had been the last scientist to leave the test tower when the first Soviet nuclear weapon was detonated.

It wasn’t easy to get to see Flerov. I had first written to the Soviet Academy of Sciences, without any response. But change was in the air of the Soviet Union: Mikhail Gorbachev was in charge and the policy of openness had been announced. Towards the end of 1988, I received a telephone call from a woman at the French Embassy in London, in the scientific attaché’s office. She told me that she had a message from Academician Flerov. He would be staying at a hotel and spa in Granville, on the Normandy coast, recuperating from a hip operation. Apart from the telephone number of the hotel, there was nothing more she would tell me.

In January 1989 I took a ferry from Portsmouth to St.-Malo. Despite the talk about reform in Moscow, the Cold War was not yet over. Leaving Portsmouth, the ferry passed close to a Russian “trawler”, moored just outside the 3-mile limit. Its upper works supported a huge array of aerials and satellite receivers, monitoring the naval base at Portsmouth. It was evening, and the ferry’s navigation lights reflected brightly off the dark sea, which was already showing signs of an expected storm. It became so rough that we could not complete the journey and docked instead at Cherbourg. At five in the morning I was on a coach that took the long coast road to St.-Malo.

Georgi Flerov was a short, bald man in his seventies, with bushy, prominent eyebrows. He had a penetrating glance, accompanied by a slightly humorous expression. We talked for about four hours, about his experiments with plutonium, his letter to the chiefs of staff and, more importantly, about arrangements to film him at the Kurchatov Institute in Moscow, which had been the first Soviet centre established for research into atomic weapons. It was named after Igor Kurchatov, the young and energetic scientist who had headed the Soviet bomb programme, and who had directed Flerov’s work leading up to the first explosion. He also mentioned that he would like us to film at his Joint Nuclear Research Institute in Dubna, where he was the emeritus professor, but he would have to negotiate separate permission for this.

I asked Flerov about the role of spies like Klaus Fuchs. He said that the information that they had supplied had saved some time, maybe one or two years at most. But everything had to be worked out, and the conventional explosives, the reactors and the plutonium had to be made in the Soviet Union by Russian scientists.

Flerov was still recuperating from his operation, and after four hours of conversation he became tired. He confirmed that he would make the arrangements for my visit to Moscow, and I left.

On the ferry back to Portsmouth I thought more about what Flerov had said. He seemed not to want to talk about the role of espionage, or the contribution of the German scientists towards the work of their Soviet counterparts. But if the information they supplied had really saved two years, then that was a long time. After all, it had taken the US only three years to build a bomb. Two years of money and labour saved was not something to be easily dismissed.

Four months later, I was on an Aeroflot flight to Moscow. The arrangements had been impossibly complicated, and permission to interview Flerov at the Kurchatov Institute had been granted only on the condition that I would use a Soviet film crew, something that I had been reluctant to accept. As it turned out, the compromise was a mistake, but that’s another story.

It was my first visit to Moscow and what I discovered came as a profound shock. A British diplomat I once interviewed told me that the Soviet Union was just Upper Volta with rockets. This was a judgement I found harsh. As a young boy I had been excited by Yuri Gagarin, the first man in space, a Russian as well, and thought the diplomat was arrogant and patronizing.

Ironically, I had been given a room in the Hotel Cosmos, on the outskirts of Moscow, past the outer ring road near to the Science Park and Kosmonaut Museum that celebrates the successes of the Russian space programme. The hotel is a massive building in the shape of a huge curved wall, with a broad spread of steps leading down to the road and, incongruously, a statue of Charles de Gaulle looking towards the heroic arch at the entrance to the park. The Cosmos was built to house foreign visitors to the 1980 Moscow Olympics and had 1,700 rooms. It was now being used by Intourist to corral visiting Western businessmen, invited to Moscow by various government departments in the first flush of Gorbachev’s effort at liberalization. The lobby and bars were full of Russian women and their pimps; they seemed to have no trouble getting past the security men at the doors, who were there to stop ordinary Russians from entering. Our Russian coordinator, who met me at the airport, explained that this was because the hotel was a hard-currency area, and that ordinary Russians would not be able to buy anything anyway. She seemed oblivious to the transactions going on at the tables around us in the bar, although it was true that the Russians were selling, not buying.

Reports in the British press about the moribund Soviet economy had not prepared me for the truth. Outside the hotel, boys of ten or eleven would rush up to any foreigner, offering Red Army cap badges or a variety of Party lapel pins in return for dollars or cigarettes. I took the metro to Red Square and went to the famous GUM store, which everybody referred to as the Soviet Harrods. There was nothing on the shelves. I found one or two bakers, which were crowded with aggressive shoppers who seemed resentful at my presence. Returning to the hotel, I stopped at a small corner shop. It was grimy, the bare floorboards caked in dirt, and all that was on display was a crate of shriveled potatoes. The hotel restaurant seemed to be as short of food as the Moscow shops. Breakfasts were a chaotic affair, with crowds of suited foreigners chasing trays of bread rolls, or hardboiled eggs, with never enough to go round. At night the only meal available was pickled fish and deep-fried chicken Kiev.

One businessman I met was the director of an English company producing heavy-duty laptop computers. He’d been invited to Moscow by the Ministry of Heavy Industry, a euphemism for the state-owned arms manufacturers, lured by a teaching deal and an offer to purchase five thousand of his expensive laptops. This would have netted his company £1 million, a decent sum in 1989. His first day had been as he expected. His driver picked him up promptly and took him to an office to address a classroom of middle-ranking bureaucrats on networks and the values of mobile computing. After three days, his driver was picking him up at eleven o’clock and half the members of his seminar didn’t turn up. At the start of the second week, he had stopped going altogether because his driver had vanished. One day he was driven instead to a government office where he was asked if he would consider a barter deal: his five thousand laptops for several million pairs of shoes. He had taken this offer seriously, but his company in the UK had told him no one was prepared to buy Russian shoes at any price. He remained in the Cosmos, in limbo.

What, I wondered, would Fuchs have made of this society? Was this what he had spied for?

On my second day, Flerov arranged to pay me a visit. In my naïvety, I did not think that he would be able to negotiate the strict security and the hordes of touts in the lobby. But I saw him walking with a slight limp down the corridor towards me. He was calm and unruffled. He had arrived in a huge black ZiL, a limousine used by high-ranking officials and Party leaders, and he had walked unobstructed into the hotel. He stayed with me for an hour, and said that he was sorry that the visit to Dubna had not been authorized; however, he would be able to tell us everything we wanted to know when we came to the Kurchatov Institute the next day.

What he went on to say revealed more about his motives for talking to me. He knew that the US work on the atomic bomb, the Manhattan Project, had been the subject of any number of books and documentaries, and he felt that it was time for his own comrades’ efforts to be recognized. In particular, too much attention was being given to the spies. Here I detected a real passion. Flerov thought that the NKGB were now claiming far too much credit for the success of the bomb project. The scientists were now fighting back to rescue their reputation.

The next day both the Soviet camera crew and the driver of the crew bus seemed reluctant to go to the Kurchatov Institute. They spoke of it as something that was secret, and they didn’t know anything about it. When we finally arrived I couldn’t understand their attitude. The ochre-walled entrance was at the end of a street called Akademik Kurchatov and there was an enormous black marble bust of the scientist, at least 20 feet high, in front of its main gate, which had a large, two-storey building as a gatehouse. At the start of the work on the Soviet atomic bomb, at the height of the war against Nazi Germany, Kurchatov had vowed never to shave his beard until the project had succeeded. The black statue reproduced the long beard that developed, but it didn’t show the sharp brain and quick-witted humour that he was reputed to possess. We drove in and were guided through extensive forested grounds to an old wooden dacha.

Entering, I was greeted warmly by Flerov, and was surprised to see that there were about twenty people assem-bled in a large room. Several tables were laid out with an enormous spread of bread, caviar, cold meat, pickles and salads. As I started to talk to some of the people in the room I realized there were several present who had also worked with Kurchatov, and they too expected to be interviewed. One woman, Zinaida Ershova, had travelled to Paris in 1937 to study under Irène Curie, Marie Curie’s daughter. Ms. Ershova had worked with Kurchatov in Moscow from the very beginning.

The film crew had set up the camera and lights in an alcove separated by some folding doors from the main room where the buffet was laid out. I noticed that the old atomic veterans had arranged their chairs in a circle so that they could observe the interview. I thought that this wouldn’t help if Flerov wanted to say anything indiscreet, but I was running out of time.

As we started filming, Flerov began to describe his impressions of Kurchatov and to tell his by now fairly well-worn story of his own letter to the High Command. His account changed little from what he had said in the spa in Granville several months before. He was not going to give away any secrets.

Then Flerov started to describe how Lavrenty Beria, head of the NKGB, had taken control of the project. This was the reason that he himself had gone to Berlin in 1945 in the uniform of an NKGB colonel. Surprisingly, he was extremely outspoken about Beria, describing him as uneducated and a thug, who understood nothing of the project. He talked about one incident when Beria asked a scientist, menacingly, if he was familiar with the inside of the Lubyanka, the NKGB’s headquarters and prison. As they got closer to the first test explosion, Beria became more and more anxious about the outcome, and all the scientists knew that their lives would be forfeit if it was a failure. I had not expected Flerov to talk about this, and during a pause to begin a new roll of film I turned around to see the reaction of the other members of the institute. We were alone. The folding doors had been quietly closed behind me and the old scientists, who had been keenly observing until then, had been hidden, safely distanced from Flerov’s attack on the head of the NKGB.

Flerov repeated his remarks that perhaps eighteen months or two years might have been saved by espionage, but how, and with what information exactly, he could not say. He personally had never seen any information from the NKGB; everything he did and worked on had been the result of discussions with other Soviet scientists. Kurchatov might have seen material from the spies, but it was a deep secret, a deadly secret, as anything to do with Beria was. And Kurchatov never talked about it.

Academician Flerov decided that the interview was over. He indicated politely that he had nothing more to say and rose from his chair. Ms. Ershova took his place. She was short and slim and must have been in her eighties. She started, with remarkable composure and apparent eloquence, an unbroken narrative that I found impossible to interrupt. She described the work that she did on the crucial problem of refining uranium, which she had begun in 1942. She talked about various accidents and explosions in the Moscow facility, and the scientists’ complete lack of understanding about the dangers of radiation. It was astounding that she was still alive. She spoke of the changes in direction and facilities when the NKGB started to fund the research in 1943, and outlined the things that the German scientists helped with, as well as the things that they knew nothing about. She too had almost nothing to say about espionage, or any other material help from the NKGB. These things, she said, had never been talked about, nobody ever knew anything about them. The German scientists, on the other hand, had been in Moscow, and later in Sukhumi on the Black Sea; they were known, and anyway their knowledge was limited to specific things.

I left the Kurchatov Institute, and Moscow, knowing nothing more about Klaus Fuchs. A few months later the Berlin Wall collapsed and the Soviet bloc went into its final economic and political meltdown. Former officers in the NKGB—or the KGB as it became after the war—started writing their biographies, or gave highly coloured interviews to Western journalists. Some of the Soviet archives were also suddenly made available to journalists and researchers, but their files were hard to decipher and the secrets of the catalogues remained in the heads of elderly ladies who seemed to be their sole guardians.

Gradually, over the years, more and more information surfaced, in the United States and in Britain. In addition, shortly before he died in 1988, Fuchs had given an interview to an East German film crew—the first time in his life that he had talked about his work as a scientist, and as a spy. This also became available with the reunification of Germany. Some MI5 files were finally released to the National Archives, although they remain heavily censored. All this means that it is now possible to piece together more fragments of the hidden history, to put some meat on the previously skeletal story of hackneyed anecdote and disinformation that passed for so many years as the account of Klaus Fuchs and his espionage. What does this new information now reveal?

For over forty years, the world was in the grip of the Cold War, and at times Armageddon seemed frighteningly close. In 1940 nuclear warfare was science fiction. Five years later it was reality. Five years after that a nuclear arms race was under way, and five years after that, by 1955, giant thermonuclear explosions were poisoning the world’s atmosphere and there seemed no limit to the destructive power that scientists could conjure out of the atom. Klaus Fuchs was connected to all of this. He played a key role in the creation of atomic weapons for each of the three wartime allies who later became the chief enemies in the Cold War, and he assisted them all in their creation of even more powerful H-bombs.

It wasn’t only his own work as a mathematician and physicist that contributed to the nuclear standoff. It was his politics and his belief in the need for political action that became a catalyst for the birth of the nuclear age. An age which, of course, has not ended, merely changed its form. Klaus Fuchs was the most important spy of the twentieth century—a spy who changed the world.

Shares