In 1967, Robert McNamara, then President Lyndon Johnson’s secretary of defense, created a secret unit in the Pentagon to collect as many internal government documents as possible relating to the Vietnam War. McNamara hoped that the collection would give officials a clearer view of the decisions that put the United States on an increasingly crisis-ridden path. It is not clear what, if anything, McNamara learned from the project. But it is clear that he could not, and did not, anticipate the journalistic bombshell he ultimately got.

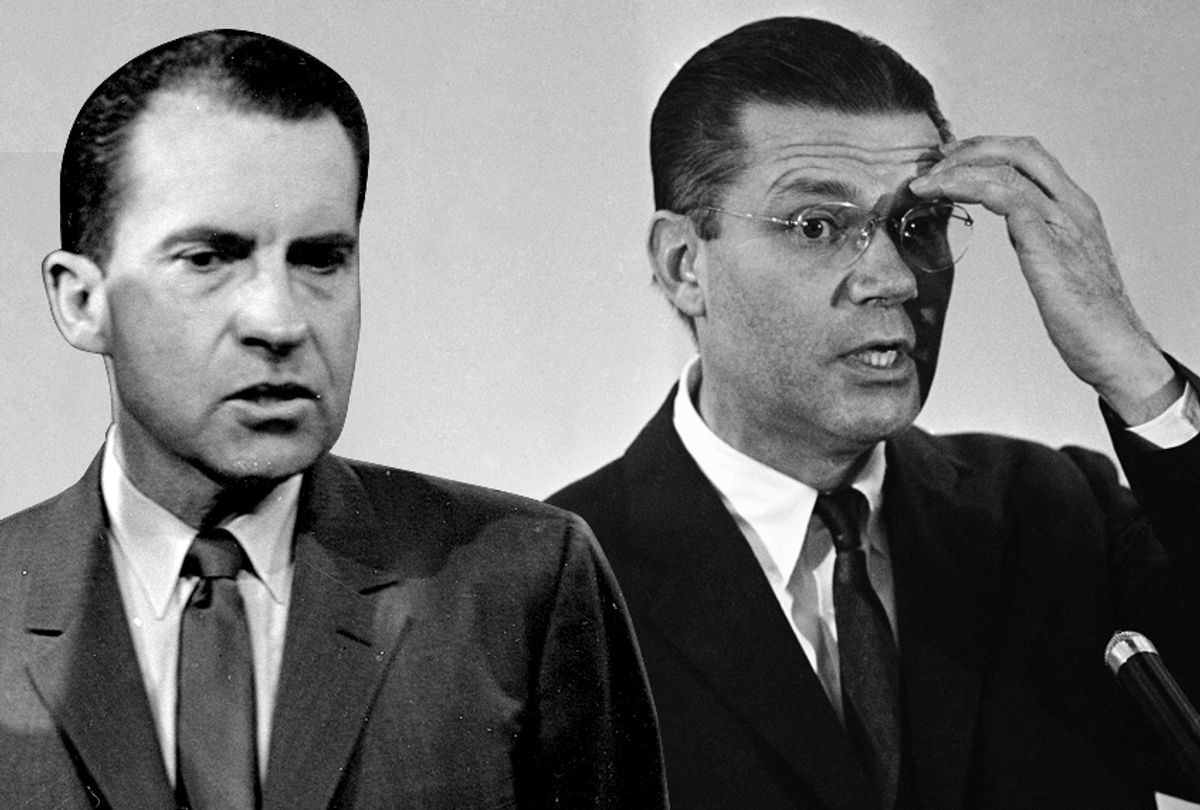

In 1971, by which time President Richard Nixon had managed to involve the United States even more deeply in the war, The New York Times published a blockbuster series of articles based on McNamara’s study. They came to be known as the Pentagon Papers, and now hold an essential place in the legacy of twentieth-century American journalism. The articles revealed, in detail and in the government’s own words, how officials had stumbled, often haphazardly, into a disastrous war that had already taken thousands of American lives.

The documents included every cable, bureaucratic memo, and note of conversation from within the government that mentioned Vietnam. They were culled not only from the White House, Pentagon, and State Department, but also from such peripheral bureaucracies as the Agriculture Department. In all, they totaled more than seven thousand documents. Their classification ranged from top secret to just plain secret.

Somewhat overwhelmed by the sheer number of classified documents, Arthur (Punch) Sulzberger, the Times publisher, asked A.M. Rosenthal, the paper’s executive editor, and me, as the appointed project editor, to brief the Times’ outside law firm, Lord Day & Lord.

“How many of the documents were classified,” the attorneys asked.

“All seven thousand,” we responded.

Shocked, the firm counseled against publishing them. When that recommendation was brushed off, Lord Day declined to represent the paper in the matter—after reportedly debating but rejecting a proposal within the firm to report the project to the Justice Department. (Years later, when asked his reaction to first hearing about the papers, Punch Sulzberger replied wryly, “Ten years to life.”)

The documents did not, as some later claimed, simply fall into the hands of The New York Times. Neil Sheehan, a Washington-based correspondent and celebrated Vietnam reporter, got a whiff of their existence, and then pursued a set of them from a senior member of the government-funded Rand Corporation, Daniel Ellsberg.

In multiple meetings between the two, Sheehan argued that Americans had a right to know how the government, especially the president, had made crucial decisions involving the war. Persuaded, Ellsberg began passing copies of the papers to Sheehan.

The copies arrived in New York in several mailbags and were eventually stashed in my Manhattan apartment, under the bed, for safe-keeping. They were then moved, suitcase by suitcase, to a makeshift editorial office set up in a suite in the Hilton Hotel. This was an essential first step. A crowded newsroom was no place for thousands of secret documents, and a leak was inevitable. Besides, our hotel hideaway allowed the editing staff to work all day and sleep in adjoining rooms at night.

From the start, our team agreed it was up to us to prove the papers’ legitimacy beyond doubt. It took weeks to spot-check hundreds of the documents against hundreds of stories already published. More than twenty books written by former government officials and laden with Vietnam references were checked against the documents to see if they matched. In every case they did.

It quickly became apparent that no one writer—even one as skilled as Neil Sheehan—could write the series alone. So Hedrick Smith, E. W. (Ned) Kenworthy, and Fox Butterfield—all veteran Vietnam reporters—were brought in. Two of the paper’s best editors—Gerald Gold and Allan Siegel, plus the Times chief librarian, Linda Amster, were recruited. Together they made sure that every sentence written corresponded to a reference in one of the documents. Adding one’s own reporting was unacceptable.

The first installment of the Pentagon Papers was published in the Times on June 13, 1971, a Sunday. The article was displayed in the center of the front page. Inside were several pages of the actual documents reproduced verbatim.

The next day, after the second installment was published, an angry Attorney General John Mitchell sent a telegram to the paper, demanding that publication be stopped. It was, Mitchell contended, a threat to national security. The next day the Times ran an article under the headline: “Mitchell Seeks to Halt Series on Vietnam But Times Refuses.” On Tuesday, after the paper had published three articles, Federal Judge Murray Gurfein slapped a restraining order on further publication.

It was immediately clear that this issue would end up in the country’s highest court. And so it did, swiftly. Left without an outside law firm, James Goodale, the head of the Times legal department, recruited Alexander Bickel, a Yale professor and one of the country’s top constitutional experts, to represent the paper. Floyd Abrams, an up-and-coming First Amendment lawyer, was added to the team.

On June 25 and 26, 1971, the Supreme Court heard the government’s argument that further publication of the papers “would cause an irreparable harm to United States national interests.”

On June 30, by a vote of six to three, the Court disagreed and upheld the Times’s right to publish. And so the paper did, until the final installment on July 5, 1971.

The articles revealed a mounting list of problems that the government faced—and often fumbled—as the Vietnam War nearly careened out of control. Decisions were clouded by Washington politics,

President Johnson’s own confused strategy, mixed signals from the battlefield, bad advice, and overconfidence, especially in evaluating an enemy’s ability to absorb punishment and continue to fight with great ferocity.

The war in Vietnam continued until April 30, 1975. By then, fifty-eight thousand Americans had been killed, more than 60 percent of them under the age of twenty-one, and three hundred thousand wounded, fighting in the jungles and hamlets and paddy fields of that Southeast Asian country.

James L. Greenfield

Project Editor, The Pentagon Papers, Former U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for Public Affairs

September 20, 2017

Shares