In this insane post-truth world of ours, it's become increasingly hard to separate fact from fiction. As a result, we’ve got presidents who comfortably refute scientific thought, and legitimate media sources categorized as "fake news." The problem boils down to profit, and the old clichéd formula "money equals power." Need another example? Look no further than the current legal war being waged against environmental activists.

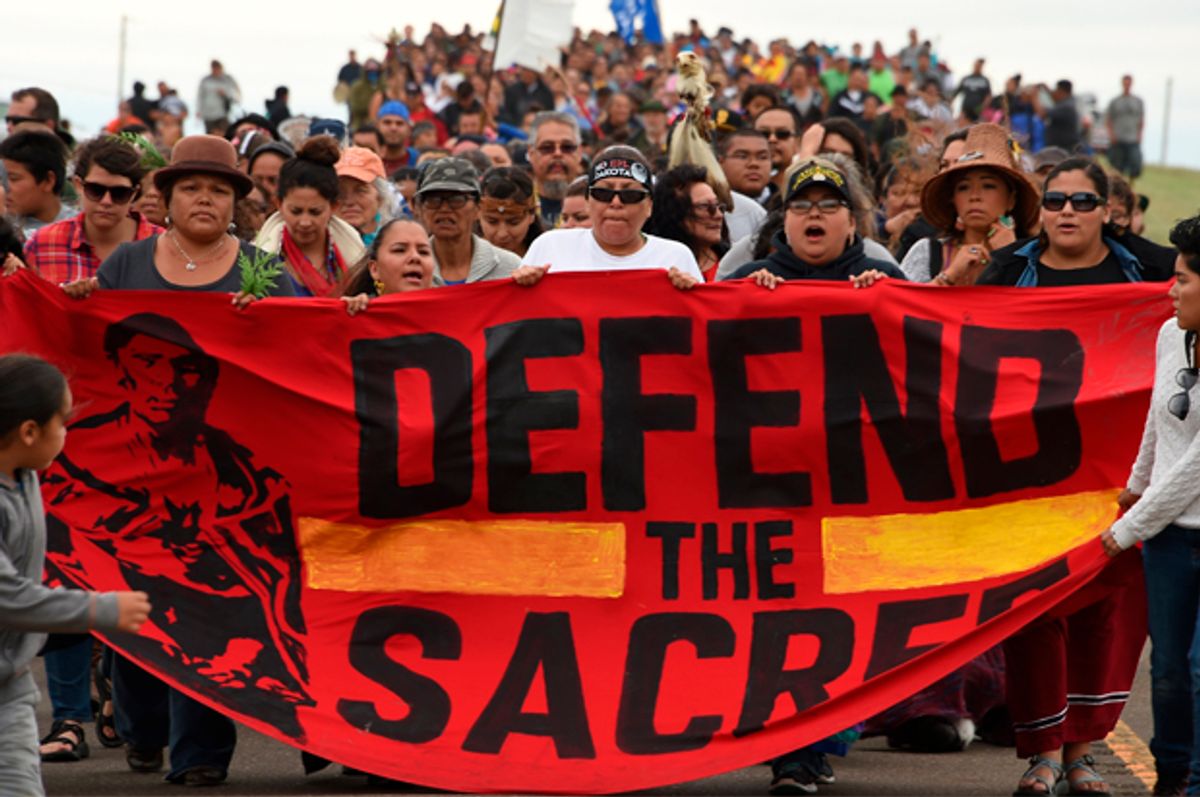

The standoff over the controversial Dakota Access Pipeline made national headlines earlier this year. In large part, this was thanks to grassroots organizations working together with larger environmental advocacy groups. Because of these efforts, millions of people were made aware of the potential hazards of this project, which helped bring construction of the pipeline to a temporary standstill. In other words, these actions had an impact. The protests proved so effective in fact, oil companies have started to pursue their own strategy for countering this sort of activism: litigation.

This past August, Energy Transfer Partners, the company responsible for the Dakota pipeline, filed a suit against Greenpeace, Banktrack and Earth First!. Under the auspices of RICO—a federal conspiracy law geared toward clamping down on racketeering—the suit alleges that these groups were involved in an illegal "enterprise" aimed at furthering their interests at the expense of the company. Adding further insult to injury, the suit also claims that Greenpeace and the others violated the terms of the Patriot Act by supporting acts of eco-terrorism and drug trafficking.

Michael Gerrard, a faculty director of climate change law at Columbia University, recently told InsideClimate News reporter Nicholas Kusnetz that "the Energy Transfer Partners lawsuit against Greenpeace is perhaps the most aggressive SLAPP-type suit” he had ever seen. Referring here to a legal acronym for lawsuits that attempt to silence political advocacy ("strategic lawsuit against public participation"), Gerrard added that the "the paper practically bursts into flames in your hands."

What is even more concerning about Gerrard's assessment is that this isn't the first RICO suit recently filed against Greenpeace. Last May it happened courtesy of Resolute Forest Products, a Canadian logging and paper company. Issued against Greenpeace and another group named Stand, the lawsuit alleged that these organizations—which have opposed Resolute's logging activities in Canada’s boreal forest for years—were conspiring to extort the company's customers and defraud its donors.

"Maximizing donations, not saving the environment, is Greenpeace's true objective," read the official complaint issued by the same legal team who represent the current litigator-in-chief, Donald Trump. The complaint goes on to note that the environmental awareness campaigns aimed at groups such as Resolute are based on "sensational misinformation untethered to facts or science" with the sole intention of inducing emotion and prompting donations to the NGO. Using this reasoning, the suit claims that the group's campaign emails and tweets constitute wire fraud.

As for "sensational misinformation," in 2012 Greenpeace Canada released a report claiming that the logging company was operating in a protected section of the boreal forest. This claim turned out to be false and Greenpeace issued an apology and retracted its material on the matter.

Does this instance actually constitute a damning claim of racketeering? As Carroll Muffett, president of the Center for International Environmental Law explained to Kusnetz, that may not even matter. "As an NGO, that is a deeply chilling argument," said Muffett, whose organization together with eight other groups filed a counter civil action in support of dismissing Resolute’s case.

For Muffett, the fact that RICO has been used more than once against Greenpeace means a dangerous precedent has been set. "This was precisely what we were concerned we would see," she added, referring to the Dakota lawsuit that lumps dozens more organizations in with Greenpeace. By referring to anyone involved in the protests as co-conspirators, Muffett explained, this suit could serve as a major deterrent for similar actions in the future. "Those groups will be looking at this and trying to decide on how to respond and what it means for their campaigns going forward," she said, "not only on Dakota Access but other campaigns as well. And that is, in all likelihood, a core strategy of a case like this."

Beyond Greenpeace, a number of other lawsuits have been filed in the past year against vocal critics. Both the New York Times and John Oliver’s “Last Week Tonight," for instance, got slammed with libel claims by Murray Energy Corp. after reporting on the Ohio-based coal company’s business practices. Another lawsuit was filed in August by Pennsylvania's Cabot Oil & Gas Corp. against a resident who accused the company of polluting residential water wells.

Joshua Galperin, head of Yale law school's environmental protection clinic, explained to Kusnetz the highly political nature of this disturbing trend. "They can change the tenor of the debate," Galperin said, referring specifically to the lawsuits against Greenpeace that equate activism with racketeering. Pointing to the stance of the current administration, Galperin added, "now wouldn't be a bad time to try these aggressive tactics, unfortunately."

Another damaging aspect of these lawsuits is the effect they could potentially have on the protest strategies used by groups such as Greenpeace. Central to the success of Greenpeace has been their “high-profile antics” writes Kusnetz, who lists as examples the time the group “sent protesters dressed as chickens to McDonald's franchises in London to protest logging in the Amazon, deftly mimicked a Dove soap public service announcement in Canada to link its parent company, Unilever, to deforestation in Indonesia, and dropped banners across the front of Procter & Gamble's corporate headquarters for its sourcing of palm oil."

The Energy Transfer Partners lawsuit explicitly refers to these tactics as the "Greenpeace Model." By creating a legal grounding for how this model equates to a form of racketeering, these suits could greatly undermine the efficacy of this strategy in the future.

"I don't think it's really about the money," Tom Wetterer, Greenpeace’s general counsel, told Kusnetz. "I think they have to realize that their claims are not strong, that it's the process that they're really focused on, regardless of the end. It's really a means to drag us through the legal process."

Shares