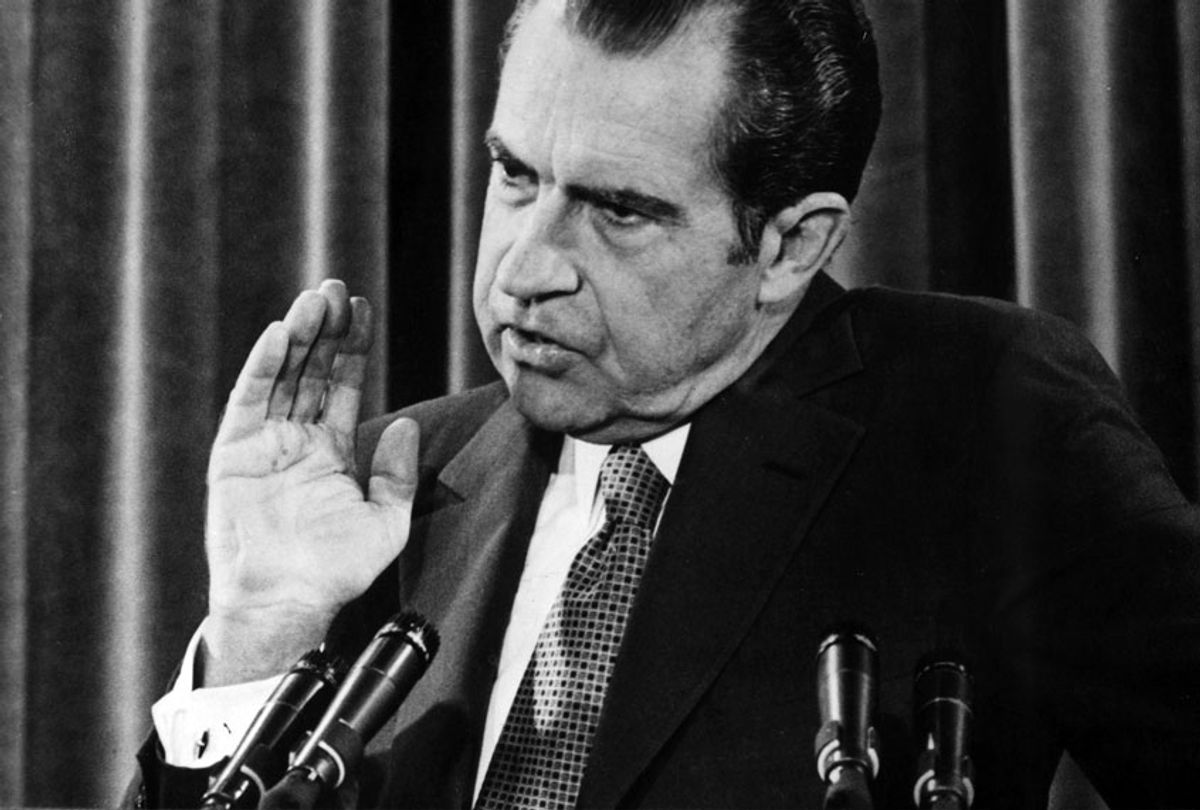

Steven Spielberg’s new movie “The Post” tells the story of the Pentagon Papers from the perspective of a single newspaper. The movie focuses on Washington Post publisher Katherine Graham’s decision to publish the Defense Department’s top secret history of the Vietnam War in defiance of the Nixon administration. The stakes are high. Nixon was the first president to claim the power to impose “prior restraint” on the press — that is, to block newspapers from publishing information he deemed injurious to national security by threatening publishers with imprisonment. Once the government convinced a federal court to grant an injunction against the newspapers, those who published the Pentagon Papers could be prosecuted for criminal contempt of court. President Richard M. Nixon remains a distant and shadowy figure in the movie, his voice heard briefly in excerpts from his (then) secret White House tapes.

A spoiler, even though this is all fairly recent history: “The Post” climaxes with the Nixon administration losing a showdown with the newspapers at the Supreme Court (and offers a brief preview of the greater newspaper drama to come for Nixon, the Post and America).

The landmark First Amendment case, while profoundly important, was only the public part of the President’s reaction to the leak. Privately, Nixon wasn’t much worried about the leak of the Pentagon Papers, since the secret history cuts off in mid-1968, months before he was even elected president. Nixon was worried about something else, something that could damage him politically — the potential leak of his own Vietnam secrets.

As the Nixon tapes record, the President quickly convinced himself that the leak of the Pentagon Papers was the work of a conspiracy that intended to leak his secrets as well.

Nixon suspected (incorrectly) that the Papers were leaked by three top officials in the branch of the Defense Department that had produced the secret history during the presidency of Lyndon B. Johnson: former Assistant Secretary of Defense for International Security Affairs (ISA) Paul C. Warnke; his deputy, Morton H. Halperin; and Leslie H. Gelb, director of policy planning and arms control for ISA. The White House soon learned the identity of the man who actually gave the Papers to the papers: Daniel Ellsberg, a defense policy analyst who had worked for the Pentagon, the State Department and the Rand Corporation. This news wasn’t enough, however, to make Nixon abandon his conspiracy theory about Warnke, Halperin, and Gelb. Acting on his conspiracy theory, the President initiated a real criminal conspiracy, the Special Investigations Unit, nicknamed “the Plumbers” because it worked on leaks. (The Plumbers came to public attention later, after two of its alumni were arrested for organizing the Watergate break-in.)

Nixon formed the unit for two illegal purposes. One was to facilitate the gathering and leaking of information about the theoretical conspiracy that was obtained through grand jury proceedings and other government investigations. The other illegal purpose was bizarre: to break into the Brookings Institution, a Washington think tank, where Nixon believed that the theoretical conspiracy had stored classified documents in a safe. The unit had legal purposes as well, such as gathering and declassifying top secret documents from Democratic administrations. “The Democratic Party will be gone without a trace if we do this correctly,” Nixon said. Even when Nixon’s means were lawful, his ends were partisan and political.

What dark secrets about Vietnam did Nixon have that he would go to such great lengths to hide? Two in particular: the Chennault Affair and the secret bombing of Cambodia.

The Chennault Affair

The Chennault Affair was Nixon’s secret effort as the 1968 Republican nominee to ensure that peace talks between North and South Vietnam did not begin before Election Day. Nixon feared, with good reason, that if peace talks got underway, they would boost the popularity of President Johnson — and of Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey, the Democratic presidential nominee.

The final month of the 1968 campaign was dominated by rumors and leaks that Johnson was on the verge of announcing the start of peace talks and a halt to American bombing of North Vietnam. Nixon saw his lead over Humphrey in the Gallup poll, 15 points at the start of the fall campaign, get cut nearly in half to eight points by mid-October and shrink all the way to two points by the final weekend of the campaign. (In the Harris poll, Humphrey actually pulled ahead.)

Throughout the campaign, Nixon had publicly promised not to interfere with the Vietnam negotiations. In his acceptance speech at the Republican convention, Nixon said, “We all hope in this room that there’s a chance that current negotiations may bring an honorable end to that war, and we will say nothing during this campaign that might destroy that chance.” Secretly, however, he urged South Vietnam to boycott the peace talks even if North Vietnam agreed to them.

President Johnson learned of Nixon’s secret efforts in the final week of the campaign, after North Vietnam agreed to all of his conditions for a bombing halt. Johnson had several sources of information: cables from the South Vietnamese embassy in Washington, D.C., intercepted by the National Security Agency, a bug planted by the Central Intelligence Agency in the office of South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van Thieu and a wiretap that Johnson ordered the Federal Bureau of Investigation to place on the embassy’s telephone. Johnson learned that Anna C. Chennault, Nixon’s top female fundraiser, was contacting South Vietnamese Ambassador Bui Diem, apparently acting as “kind of the go-between” for the Nixon campaign and the Saigon government, urging Saigon away from the peace talks. (What Johnson did not know was that Nixon had held a secret meeting with Chennault, Diem and Nixon Campaign Chairman John N. Mitchell in New York, months earlier. As Chennault later revealed in her memoirs, Nixon told the ambassador, “Anna is my good friend. She knows all about Asia. I know you also consider her a friend, so please rely on her from now on as the only contact between myself and your government. If you have any message for me, please give it to Anna and she will relay it to me and I will do the same in the future. We know Anna is a good American and a dedicated Republican. We can all rely on her loyalty.” John Farrell, author of the magisterial 2017 biography "Richard Nixon: The Life," discovered contemporaneous evidence Chennault spoke for Nixon himself: handwritten notes by Chief of Staff H.R. “Bob” Haldeman on an order Nixon gave on October 22, 1968 to “keep Anna Chennault working on SVN [South Vietnam].”)

President Johnson announced a bombing halt and the start of peace talks in which South Vietnam “was free to participate” in a nationally televised address on October 31, 1968. Two days later, on the Saturday before the election, President Thieu publicly announced that the South would not attend the peace talks. That same day, the FBI wiretap overheard Chennault telling Ambassador Diem “that she had received a message from her boss (not further identified) which her boss wanted her to give personally to the ambassador. She said the message was that the ambassador is to ‘hold on, we are gonna win.’” Johnson was understandably outraged. “This is treason,” he thundered at Sen. Minority Leader Everett M. Dirksen, R-Ill. Dirksen’s quiet reply: “I know.” Nixon, however, admitted nothing.

Nixon won the election by less than 1 percentage point and credited Thieu’s boycott with the small margin of victory he managed to eke out. Since President Johnson let him know that the government had detected the interference with the peace negotiations, but did not tell exactly what or exactly how, Nixon became understandably obsessed with getting his hands on every government document having to do with the bombing halt. In his first month in office, President Nixon ordered Haldeman to put together a complete report with “all the documents.” Haldeman assigned the project to Tom Charles Huston. During the Watergate hearings, Huston would become notorious as the author of the “Huston Plan” to expand government break-ins, wiretaps and mail-opening, all in the name of combating domestic terrorism. At the time, Huston was a little-known White House aide. He gave his bosses some bad intel. Huston said that ISA (the Pentagon division that produced the Pentagon Papers) had put together a report “on all events leading up to the bombing report.” He mentioned two of the men, who later appeared in Nixon’s conspiracy theory, saying that Paul Warnke had a copy of the alleged bombing halt report and that the responsibility for securing the file had fallen to Les Gelb, then a fellow at Brookings. There’s no evidence this bombing halt report actually existed. Huston or one of his sources may have been confused about the Pentagon Papers — which can accurately be described as a report on all the events leading up to President Johnson’s announcement of a partial bombing halt on 31 March 1968, in the same speech he announced his decision not to seek another term as president.

Nixon, nevertheless, was convinced. On his tapes, he can be heard ordering a break-in at Brookings to obtain the alleged bombing halt report. The reason Nixon gave his aides for wanting the report so badly was that he needed proof that Johnson had called the bombing halt for political reasons, to elect Humphrey. As motives go, this makes little sense. The diplomatic record shows that Johnson set three conditions for the North Vietnamese: in return for a bombing halt, they had to (1) respect the demilitarized zone (DMZ) dividing North and South Vietnam, (2) sit down with the South Vietnamese for peace talks and (3) stop shelling civilian centers in South Vietnamese cities. For most of 1968, Hanoi refused to accept any of Johnson’s conditions, but in October of that year, they accepted all three. The bombing halt took place before the election because that’s when Hanoi agreed to Johnson’s demands. Even Huston, who did his own bombing halt report for Nixon, concluded that Johnson was not guilty of playing politics with war in the manner Nixon alleged. Besides, Nixon had no need for blackmail-style leverage over Johnson, since there was little Johnson could do for him. Above all, breaking into Brookings posed an enormous risk. It was a crime that, if traced back to Nixon, could get him not only impeached but imprisoned as well. Why take such an enormous personal and political risk just to have something to hold over the head of retired president? The only compelling reason Nixon had to steal the alleged bombing halt report would be to cover his tracks regarding the Chennault Affair.

Sabotaging the peace talks to win an election was a violation of the Logan Act and a scandal waiting to happen, since the facts of the affair demonstrated Nixon’s willingness to put politics above the lives of American soldiers. In all likelihood, Nixon was afraid of leaving evidence of the Chennault Affair in the hands of men who had worked for one Democratic president and were likely to serve as advisers to his 1972 Democratic opponent.

The secret bombing of Cambodia

One of the first major decisions Nixon made as president was to send American B-52s to bomb the Ho Chi Minh Trail in Cambodia. North Vietnam used the Cambodian border area to infiltrate soldiers and supplies into South Vietnam, and the bombing was meant to disrupt that flow. It did much more, commencing a spiral of violent unintended consequences that quickly descended into disaster.

The first disaster was that the bombing drove the North Vietnamese deeper into Cambodia. They had no other direction to run to avoid the destructive power of B-52 bombs. If they moved north or south on the Trail, they’d still be bombing targets. The same would hold true if they fled into South Vietnam, since the U.S. had deployed B-52s on the South Vietnamese side of the border for years. The only way to avoid the B-52s was to head west, further into Cambodia. So they did.

That led to the next disaster. Rural Cambodians did not take kindly to the appearance of North Vietnamese soldiers near their villages. Some took up arms against the invaders. While Prince Norodom Sihanouk had kept Cambodia officially neutral regarding the Vietnam War, it was difficult to maintain neutrality when the country’s citizens and North Vietnamese soldiers were engaged in armed clashes.

Cue the next disaster: A right-wing coup that replaced Prince Sihanouk with a government that took a hard line against North Vietnamese infiltration. At first, this seemed like a pretty good thing for America. But Hanoi responded by sending troops toward the Cambodian capital of Phnom Penh, with the intention of installing a pro-Hanoi government headed by Prince Sihanouk, who was willing to abandon neutrality if it meant he could return to power. By April of 1970, Hanoi was close to achieving its goal. Nixon saw that as a looming disaster. If Hanoi got an ally on South Vietnam’s western border, its infiltration would increase and enjoy the protection of the Cambodian government. Nixon ordered American troops into Cambodia to avoid a great military setback, an action that did help keep the North Vietnamese from toppling the Cambodian government.

But the invasion of Cambodia spread the disaster into America, by touching off the largest antiwar demonstrations to date. The Kent State massacre occurred less than a week after Nixon announced the invasion, but the shooting of four students by National Guardsman was only one of many incidents of violence and unrest that erupted in the wake of the military action the White House minimized as an “incursion.” It drew greater public opposition than any previous escalation of the war.

And that was when Americans did not yet know that Nixon had, unintentionally, sent the snowball rolling downhill by secretly bombing Cambodia. More than a year after the invasion, he remained determined to keep Americans in the dark about the bombing.

Which brings us to the third man in Nixon’s supposed conspiracy, Morton Halperin. National Security Adviser Henry A. Kissinger had hired Halperin to work in the Nixon White House in 1969. Nixon hated having a veteran of the Johnson administration on his National Security Council staff. When some details of the secret bombing appeared in the Times in May of that year, Nixon had the FBI place a wiretap on Halperin’s home telephone. Although the tap produced no evidence that Halperin had disclosed classified information to any journalist, Nixon continued it after Halperin left the NSC staff in August 1969 — and even after Halperin started serving as an adviser to Sen. Edmund S. Muskie, D–Maine, then the front-runner for the Democratic presidential nomination.

The leak of the Pentagon Papers revived Nixon’s fears about Halperin and the possibility that the secret bombing of Cambodia would leak as well.

What follows is a timeline of Nixon’s reactions, from the day the New York Times printed its first Pentagon Papers story (June 13, 1971) to the day after the Supreme Court ruled that newspapers could continue to publish the classified study (July 1, 1971). It traces Nixon’s swift descent into paranoia and lawlessness, the beginning of his end.

Sunday, June 13, 1971

The New York Times publishes part one of a series headlined, “Vietnam Archive: Pentagon Study Traces 3 Decades of Growing US Involvement.” The series is based on a 3,000-page classified study of “United States-Vietnam Relations, 1945-1967,” produced by the Defense Department’s International Security Affairs (ISA) branch in the final years of the Johnson administration. The study includes an additional 4,000 pages of complete government documents. It is, in the words of the Times, “the most complete and informative central archive available thus far on the Vietnam era.” The Times refers to the 7,000-page archive as “the Pentagon papers.”

Government deception emerges as a theme. The archive confirms that the Johnson administration had deceived Congress in August 1964 as it sought the passage of the Tonkin Gulf Resolution authorizing the president to “take all necessary measures to repeal any armed attack against the forces of the United States.” The administration had claimed that North Vietnamese PT boats had attacked American destroyers in the gulf without any provocation. “The Pentagon papers disclose that . . . the United States had been mounting clandestine military attacks against North Vietnam and planning to obtain a congressional resolution that the administration regarded as the equivalent of a declaration of war,” the Times reports.

President Richard M. Nixon’s initial reaction to the Pentagon papers is indifference: “I didn’t read the story.”

Deputy National Security Adviser Alexander M. Haig speculates that the Papers were leaked by four former Johnson administration officials who oversaw the study: Defense Secretary Clark M. Clifford, Assistant Secretary for ISA Paul C. Warnke, Deputy Assistant Secretary for ISA Morton H. Halperin, and Director of Policy Planning and Arms Control Leslie H. Gelb. Haig’s suspicions will turn out to be unfounded, but Nixon soon forms a conspiracy theory about Warnke, Halperin and Gelb, fearing that they were leaking the Pentagon Papers as a prelude to leaking some of Nixon’s most potentially damaging secrets.

National Security Adviser Henry A. Kissinger says the leak will not harm the administration at home but will hurt its negotiating position vis-a-vis North Vietnam: “Basically, it doesn’t hurt us domestically. I think, I’m no expert on that, but no one reading this can then say that this president got us into trouble. I mean, this is an indictment of the previous administration. It hurts us with Hanoi because it just shows how far our demoralization has gone.”

Nixon and Kissinger privately denounce the leak as “treasonable.”

Monday, June 14, 1971

The Times publishes part two of the Pentagon Papers series: “Vietnam Archive: A Consensus to Bomb Developed Before ’64 Election, Study Says.”

At his first meeting of the day, President Nixon expresses concern about leaks occurring during the 1972 campaign.

Nixon worries that Morton Halperin, one of Haig’s suspects, will reveal the secret bombing of Cambodia, code-named Operation Menu. “How much does Halperin know? Does he know about the Menu series?” Nixon asks Haldeman.

Nixon directs Haldeman to have a U.S. senator make a speech leveling the baseless accusation that the Pentagon Papers leak was the work of Leslie Gelb, another Haig suspect. Since there is no evidence to support this charge, Nixon suggests that the speech be made on the floor of the U.S. Senate, where senators enjoy the constitutional privilege of making any statement, true or not, without fear of legal action. “They can’t be sued,” says Nixon.

White House Chief of Staff H.R. “Bob” Haldeman says, “To the ordinary guy, all this is a bunch of gobbledygook. But out of the gobbledygook comes a very clear thing, which is: you can’t trust the government, you can’t believe what they say, and you can’t rely on their judgment. And that the implicit infallibility of presidents, which has been an accepted thing in America, is badly hurt by this, because it shows that people do things the President wants to do, even though it’s wrong. And the President can be wrong.”

Nixon rails against the Brookings Institution, the Washington think tank where Halperin and Gelb have both become senior fellows. “Those people—that’s the Democratic National Committee!” says Nixon. “We don’t have one man at Brookings, Bob.” He directs Haldeman to have Brookings falsely implicated in the Pentagon Papers leak as well. “Charge Brookings. Let’s get Brookings involved in this. Get Brookings involved,” says Nixon. “It has to be done. Let’s smoke Brookings out. Smoke them out. And the way to do it is through a [congressional] speech probably better than an art—than a column.”

Haig tells Nixon that former President Johnson and former National Security Adviser Walt W. Rostow think they know who was behind the leak. Haig says he spoke to Rostow “late last night and he said, ‘Now, I don’t want to cast any aspersions about who might have done this, but our strong suspicion is it’s Dan Ellsberg.’” Rostow does not believe Halperin or Gelb took part, says Haig.

“Ellsberg. I’ve never heard his name before,” says Nixon.

At 7:13 p.m., Chief Domestic Policy Adviser John D. Ehrlichman calls Nixon to say, “Mr. President, the Attorney General [John N. Mitchell] has called a couple times about these New York Times stories, and he’s advised by his people that unless he puts the Times on notice, he’s probably going to waive any right of prosecution against the newspaper. And he is calling now to see if you would approve his putting them on notice before their first edition for tomorrow comes out.”

Nixon is reluctant. “Hell, I wouldn’t prosecute the Times. My view is to prosecute the goddamn pricks that gave it to them,” Nixon says. Nixon asks if they can wait one more day, since the Times plans to publish part three of the Pentagon Papers series the next day.

Ehrlichman says Mitchell feels that the Justice Department must give the Times “some sort of advance notice.”

Nixon asks Attorney General Mitchell, “Has the government ever done this to a paper before?”

“Oh, yes,” says Mitchell.

“Have we? All right,” says Nixon. “How do you go about it, you do it sort of low key?”

“Low key. You call them and then send a telegram to confirm it,” says Mitchell. The Attorney General doesn’t mention that the Justice Department will threaten to seek an injunction blocking the Times from further publication of the Pentagon Papers.

“Well, look, look, as far as the Times is concerned, hell, they’re our enemies. I think we just ought to do it,” Nixon says. The President’s entire decision-making process for launching an unprecedented First Amendment case takes less than 10 minutes.

At 7:30 p.m., Assistant Attorney General for Internal Security Robert C. Mardian calls Harding F. Bancroft, executive vice president of the Times. Mardian requests that the Times cease publication of the Pentagon Papers voluntarily. If it does not, Mardian says the Justice Department will seek an injunction forcing it to do so.

An hour later, the Times received a telegram from Mitchell saying that publication of the Pentagon Papers is a violation of the Espionage Act. “Moreover, further publication of information of this character will cause irreparable injury to the defense interests of the United States,” the telegram says. Mitchell requests that the Times cease publication of the series and turn over the documents to the Defense Department.

The newspaper quickly responds: “The Times must respectfully decline the request of the Attorney General, believing that it is in the interest of the people of this country to be informed of the material contained in this series of articles.” The Times announces its intention to fight the threatened injunction. “We will of course abide by the final decision of the court,” the Times says.

Tuesday, June 15, 1971

The Times publishes part three of the series: “Vietnam Archive: Study Tells How Johnson Secretly Opened Way to Ground Combat.”

The Times previews part four: “Tomorrow: The Kennedy Administration increases the stakes.”

Nixon orders White House staff to cut off the Times. “Until further notice under no circumstances is anyone connected with the White House to give any interview to a member of the staff of the New York Times without my express permission,” Nixon writes in a memo to Haldeman. “I want you to enforce this without, of course, showing them this memorandum.”

In the Oval Office, Nixon pounds the desk as he tells Haldeman, “Now incidentally let me tell you, it’s very, very important to get to Henry [Kissinger] right away on that. [Unclear.] He must never return a call to the Times. Never. Not [Times reporter] Max Frankel. No Jew. No nothing.” Kissinger is the one member of Nixon’s inner circle who is Jewish.

The president pounds the desk some more as he calls for the leaker to be prosecuted as a criminal: “Now goddamn it, somebody’s got to go to jail on that. Somebody’s got to go to jail for it. That’s all there is to it.”

Later, Kissinger says, “The reason you have to be so tough, also, Mr. President, is because if this thing flies on the New York Times, they’re going to do the same to you next year. They’re just going to move file cabinets out during the campaign.”

“Yeah, they’ll have the whole story of the Menu series,” Nixon says, referring to the secret bombing of Cambodia.

Nixon rejects the Times’ argument that publishing the Pentagon Papers serves the public good: “There is no cause that justifies breaking the law of this land. Period.”

Nixon privately denounces the Times, who obtained the Pentagon Papers: “Neil Sheehan of the New York Times is a left-wing Communist son of a bitch. He has been for at least 20 years to my knowledge.”

U.S. District Judge Murray I. Gurfein issues a temporary restraining order blocking further publication of the Pentagon Papers by the Times. It is Gurfein’s first day on the bench. He is a Nixon appointee.

Alexander M. Bickel, a Yale law professor and the Times’ lawyer, says this is the first time the federal government has tried to impose “prior restraint” — that is, to get a court order to suppress the publication of newspaper articles, so that any further publication would be punishable as contempt of court. “It has never happened in the history of the republic,” Bickel says. In 1931, the Supreme Court struck down a state attempt to exercise prior restraint. “It is of the essence of censorship,” Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes wrote.

The Justice Department files suit to make the court order permanent. The government argues that “serious injuries are being inflicted on our foreign relations.”

When Nixon realizes that the temporary restraining order means the Times cannot run its planned stories on the Kennedy administration, he says, “It’s the wrong time to restrain them.”

Attorney General Mitchell says, “Well, with the facilities we have in this government, if we want it out, we can leak it, and they’ll put it in the New York Times.” The president’s men laugh.

Kissinger tells Nixon that Olof Palme, prime minister of Sweden, said the Pentagon Papers prove that America paved the path to war with deceit.

Nixon says Palme’s statement is “part of the conspiracy, in my opinion.”

“Oh, yeah,” Kissinger says.

“He wouldn’t otherwise pay any attention to it. Somebody got to him. Henry, there is a conspiracy,” Nixon says. “You understand?

“I believe it now,” Kissinger says. “I didn’t believe it formerly, but I believe it now.”

Wednesday, June 16, 1971

The New York Times suspends publication of the Pentagon Papers in compliance with the temporary restraining order, delaying publication of articles on the Kennedy administration.

In the Oval Office, President Nixon tells Haldeman, “Let me say that I think the Kennedy stuff should get out. I’d like to have somebody analyze if I could do that. Maybe, maybe [have] Haig do that. What does it tell about the Kennedy thing? Now the way it would be getting out is not to put out any documents, just to put out the . . . see, the injunction runs only to the Times, Bob. Right?”

“Yeah,” Haldeman says.

“So let somebody else — just get it out to somebody else,” Nixon says.

“Well, if you release all of it to the Hill, then you can get a Hill guy to start talking about that. And if you declassify, you can declassify that,” Haldeman says.

Nixon tells White House Press Secretary Ronald L. Ziegler to tell reporters that “this administration is not trying to hide anything.” Information about ongoing negotiations over nuclear arms, Berlin, and Vietnam must remain classified, Nixon says. “The obligation of whoever is president of the United States is to protect the integrity of government,” Nixon says. “We’re not trying to hide anything, because we have nothing to hide.”

Ziegler tells Nixon that Newsweek is about to identify Ellsberg as the newspapers’ source. “He’s got to go to jail,” the President says.

“The stuff on Kennedy I’m going to get leaked,” Nixon says. “Only the New York Times is enjoined. Nobody else is enjoined. So now that it’s being leaked, we’ll leak out the parts we want.” [Conversation 523‑006, 16 June 1971, 5:16–6:05 p.m.]

The Canadian government objects to the account in the Pentagon Papers of its role as an intermediary between the United States and North Vietnamese governments.

Thursday, June 17, 1971

To deflect criticism, the White House seeks to persuade Johnson to hold a press conference condemning the leak. “The press would bait him, and he’d overreact, and it would become the battle between Lyndon Johnson and the New York Times,” Haldeman says.

Nixon tells aides to accuse the Times of “giving aid and comfort to the enemy,” the constitutional language defining treason. “They did this for purposes of hurting us, of course, and hurting the nation. Now they’re going to pay,” Nixon says.

Pulitzer Prize-winning Times journalist “Arthur Krock used to always say, ‘Never strike a king unless you kill him.’ They struck and did not kill. And now we’re going to kill them. That is what I will do, if it’s the last thing I do in this office. I don’t care what it costs. They’re going to be killed. If I can kill ’em,” Nixon says.

The President contemplates arguing the case before the Supreme Court. “[Justice Hugo] Black and the rest of them would take out after me like gangbusters, and I’d knock their goddamn brains out,” he says.

Nixon tells Kissinger to have one of his staff leak the section of the Pentagon Papers on President John F. Kennedy’s role in the overthrow of South Vietnamese President Ngo Dinh Diem. “Now goddamn it, Henry, I want to get out the stuff on the murder of Diem. Get one of the little boys over in your office to get it out,” Nixon says.

“My guy shouldn’t put out classified documents,” Kissinger says.

“Get it out. I’m going to put it out. I want to see the material,” Nixon says.

“Mr. President, it’s in these volumes, and they’re going to come out one way or the other in the next few weeks,” Kissinger says.

“They aren’t going to use that,” Nixon says. “They won’t use the Diem part. Never.”

Haldeman suggests that Nixon try “blackmail” to get Johnson to hold a press conference. “Huston swears to God there’s a file on [the bombing halt] at Brookings,” Haldeman says.

The bombing halt file would show that Johnson had ordered the bombing halt for political purposes, Nixon says. “Bob, now you remember Huston’s plan? Implement it,” Nixon says. “I mean, I want it implemented on a thievery basis. Goddamn it, get in and get those files. Blow the safe and get it.”

Friday, June 18, 1971

The Washington Post, having obtained a copy of the Pentagon Papers from Ellsberg, publishes the first article in a series: “Documents Reveal US Effort in ’54 to Delay Viet Election.”

Sen. Edward M. “Ted” Kennedy, D-Mass., calls on the Nixon administration to declassify the parts of the Pentagon Papers on President John F. Kennedy, the senator’s brother.

Twenty Democratic members of the House of Representatives announce plans to file an amicus curiae (“friend of the court”) brief with Judge Gurfein in support of the Times’ right to publish.

Two House committees announce plans to hold hearing on the Pentagon papers.

Members of both parties call on the executive branch to furnish a copy of the secret history to Congress.

President Nixon visits Rochester, New York, then flies to Key Biscayne, Florida, for a long weekend.

The government seeks an injunction against the Post.

U.S. District Court Judge Gerhard Gissell denies the injunction, finding no evidence that publication would harm national security. “What is presented is a raw question of preserving the freedom of the press as it confronts the efforts of the government to impose a prior restraint on publication of essentially historical data,” Gissell says in the decision.

The Justice Department asks the Federal Court of Appeals to reverse Gissell ruling.

Saturday, June 19, 1971

At 1:20 a.m., after three hours of argument, a three-judge panel of the Federal Court of Appeals votes 2-to-1 to grant the government a temporary restraining order against the Washington Post.

The court allows the Post to continue printing its Saturday edition, complete with the second part of its Pentagon Papers series: “Johnson Administration strategists had almost no expectation that the many pauses in the bombing of North Vietnam between 1965 and 1968 would produce peace talks, but believed they would help placate domestic and world opinion, according to the Defense Department’s study of those war years.”

In New York, Judge Gurfein denies the government a permanent injunction against the New York Times. “This court does not doubt the right of the government to injunctive relief against a newspaper that is about to publish information or documents absolutely vital to current national security. But it does not find that to be the case here,” Gurfein says in his decision.

The judge does, however, extend the temporary restraining order to give the government time to appeal.

Judge Irving Kaufman of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit upholds the temporary order against the Times.

Sunday, June 20, 1971

The New York Times and the Washington Post obey the temporary restraining orders barring publication of the Pentagon Papers.

The Times devotes a front-page story to a White House statement arguing that legal action against the newspapers is necessary because the government “cannot operate its foreign policy in the best interests of the American people if it cannot deal with foreign powers in a confidential way.”

Time magazine reports that former President Johnson says the leak comes “close to treason” and the secret history itself is biased and dishonest. The magazine names no sources for the story.

Monday, June 21, 1971

The Boston Globe starts publishing the Pentagon Papers. The Globe reports that in October 1961, Gen. Maxwell D. Taylor advised President Kennedy to send an 8,000-soldier combat task force to Vietnam. JFK declined, but increased the number of American advisers in South Vietnam to 16,000 over the next two years and increased covert actions against North Vietnam.

The government obtains a temporary restraining order against the Globe.

Judge Gesell refuses to extend the temporary restraining order against the Washington Post for a second day. “There is no proof that there will be a definite break in diplomatic relations, that there will be an armed attack on the United States, that there will be a war, that there will be a compromise of military or defense plans, a compromise of intelligence operations, or a compromise of scientific and technological materials,” Gesell says in his decision.

Minutes later, the Federal Court of Appeals stays Gesell’s decision and extends the restraining order another day.

Tuesday, June 22, 1971

The Boston Globe and Chicago Sun-Times begin publishing the Pentagon Papers.

The Globe reports that President Johnson’s decision to reduce American troops in Vietnam shortly before he announced a halt to American bombing of most of Vietnam, as well as his decision not to seek another term as president, on 31 March 1968.

The Sun-Times reports that the Kennedy administration had advance knowledge of the November 1963 coup d’état that overthrew President Ngo Dinh Diem of South Vietnam.

Sen. Paul N. “Pete” McCloskey, R-Calif., says the Pentagon Papers in his possession show that the U.S. government “encourage and authorized” the Diem coup.

U.S. District Court Judge Anthony Julian issues a temporary restraining order against the Boston Globe.

Two U.S. Courts of Appeals extend the temporary restraining orders against The New York Times and the Washington Post.

President Nixon returns to the White House from Key Biscayne.

The President is briefed on opinion polls. Some results suggest great public opposition to the publication of the Pentagon Papers, others great support.

- Q: Do you think freedom of the press includes the freedom of a paper to print stolen, top secret government documents? A: Yes–15 percent. No–74 percent.

- Q: Do you feel the government is trying to suppress information the public should have? A: Yes–62 percent. No–28 percent.

- Q: Did the Times break the law when it published this secret material or was the publication legal? A: Broke the Law–26 percent. Legal–48 percent.

- Q: Even if it was illegal for the Times to publish the secret study, do you think they did or did not do the right thing in bringing these facts about Vietnam to the American people? A: Did the Right Thing–61 percent. Did Not–28 percent.

President Nixon reacts to the court rulings against him by privately railing against Jews and the Establishment: “I think of all those damn New York Jews are doing it. It’s the circuit court up there. And here in Washington it’s the Washington types.” [See Conversation 527‑012, 22 June 1971, 5:09‑6:46 P.M., Oval Office.]

Informed that Ellsberg’s ex-wife is testifying against him in grand jury proceedings, the President says, “You’ve got to get it out.” (Leaking grand jury testimony would be a violation of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure.)

“Now, wait a minute, wait a minute, I don’t want to go to jail,” Attorney General Mitchell says, provoking laughter in the Oval Office.

“Of course, if I’m going to jail, I want to go in a hurry, so I might get a pardon,” Mitchell says.

“Ha. You bet,” the President says.

“Don’t count on it,” Chief Domestic Policy Adviser Ehrlichman says, to more laughter.

Wednesday, June 23, 1971

The Los Angeles Times and the Knight newspaper chain begin publishing the Pentagon Papers.

The Los Angeles Times reports that in August 1963, one State Department official doubted that the Diem regime would last another six months.

The Knight newspapers report that in December of 1967, a group of outside scientists determined that American bombing had been so ineffective that the North had become a stronger military power than it was before the bombing began.

President Nixon announces that Congress would be allowed to read all 47 volumes of the Pentagon Papers. He insists that they remain classified.

“The Kennedy myth is going to be tarnished by this,” President Nixon says privately.

White House Special Counsel Charles W. “Chuck” Colson says the Boston Globe story caused “great writhing in pain in the streets of Boston yesterday.”

Nixon wants the administration to declassify documents from foreign policy crises that occurred during Democratic administrations: World War II, the Korean War, the Bay of Pigs and the Cuban Missile Crisis.

“The beauty is we can do this selectively. We can look at it and put out what we want when we want,” Haldeman says.

Nixon sets the administration’s public line: “The president is doing the only thing he can. He has to carry out the law.”

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit rules 5-to-3 that the Times can resume publishing the Pentagon Papers after Friday, June 25, 1971. The ruling, however, prohibits the Times from publishing specific material that the government says would endanger national security.

Times publisher Arthur Ochs Sulzberger says the newspaper will appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Nixon tells Colson, “Get [Rep.] Jack Kemp, [R–N.Y.], to demagogue. Tell him to get out and make, you know, irresponsible charges. That’s what they have to do in order to get attention. They say this is treasonable—treasonable—and, you know, don’t worry about it.”

Warnke tells reporters that the leak of the Pentagon Papers on diplomacy could cause problems. (Ellsberg did not leak the diplomacy volumes.)

CBS News airs an interview with Ellsberg.

Thursday, June 24, 1971

The Federal Court of Appeals rules that the government has not shown grounds to block publication of the Pentagon Papers by the Washington Post.

The government appeals to the Supreme Court.

The Baltimore Sun reports that after the 1964 election, President Johnson doubted that the air war against North Vietnam would be effective.

The government announces it is not seeking injunctions against the Los Angeles Times or the Knight newspapers “at this time.”

Friday, June 25, 1971

The Supreme Court agrees to hear arguments on the Pentagon Papers case during a rare Saturday session. Chief Justice Warren E. Burger signs an order extending the temporary restraints on the New York Times and Washington Post. Four Justices dissent, saying both newspapers should be free to publish.

The Justice Department announces it has a warrant for the arrest of Ellsberg on charges of “unauthorized possession of top-secret documents and fail[ure] to return them.”

The St. Louis Post-Dispatch starts publishing the Pentagon Papers with a story saying that in 1966 former Defense Secretary McNamara called the pacification program “a bad disappointment.”

The Los Angeles Times reports that President Johnson’s March 1965 decision to send 3,500 marines to protect the air base at Da Nang paved the way for the later introduction of American combat troops on a much larger scale.

Publishers, editors and journalists testify before a House Government Operations subcommittee that the government’s suppression of the Pentagon Papers amounts to censorship.

Saturday, June 26, 1971

Before the Supreme Court, Solicitor General Erwin N. Griswold says publication of some of the Pentagon Papers would jeopardize American foreign policy. “It will affect lives. It will affect the process of the termination of the war. It will affect the process of recovering prisoners of war,” Griswold says.

Lawyers for the New York Times and Washington Post say the government is making “broad claims with narrow proof.”

“Conjecture piled upon surmise does not justify suspending the First Amendment,” says William R. Glendon, lawyer for the Post.

After hearing two hours of arguments, the Supreme Court adjourns without announcing a decision.

Ellsberg announces plans to surrender voluntarily to the U.S. attorney in Boston on Monday. His lawyers say he has not committed any crime.

The Justice Department rejects the offer, saying the hunt for Ellsberg will continue.

The Knight newspapers report that the U.S. military pressured President Johnson to expand the Vietnam War into the bordering nations of Laos and Cambodia in 1966 and 1967. The papers also report that in 1966, the Central Intelligence Agency informed Johnson that 80 percent of the casualties of American bombing of North Vietnam were civilians.

A U.S. District Court issues a temporary restraining order against the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

Monday, June 28, 1971

The government indicts Ellsberg on charges of unauthorized possession of secret documents and of converting government property to personal use.

Before appearing in court, Ellsberg says, “Obviously, I didn’t a think that a single page out of the 7,000 pages in the study would cause a grave danger to the country or I would not have released the papers, and from what I’ve read in the paper, the government has not made a showing that the papers contain such a danger.”

The Defense Department delivers a copy of the Pentagon Papers to Congress. Defense Secretary Melvin R. Laird says disclosure would risk “grave and immediate dangers to national security.”

Tuesday, June 29, 1971

Meeting with his Cabinet, President Nixon threatens to fire the head of the agency from which the next leak comes. Chief of Staff Haldeman will be “the Lord High Executioner.” The President says 96 percent of the bureaucracy is against the administration. He says these employees are “a bunch of vipers that are ready to strike” and “left-wing bastards that are here to screw us. Now, this is a fact.”

“I want you to take the hard line that we cannot govern this country, you really can’t govern this country, if a man is not prosecuted for stealing documents,” Nixon tells Haldeman when they are alone. “It is tough, Bob. It is tough to live in this town. We’re going to fight. And we’ll have more on our side than you think. You know, we’ve got more on our side than you think. People don’t trust these Eastern Establishment people. He’s Harvard. He’s a Jew. You know, and he’s an arrogant intellectual.”

Wednesday, June 30, 1971

In the morning, the Christian Science Monitor reports that the United States “ignored eight direct appeals for aid from North Vietnamese Communist leader Ho Chi Minh in the first five winter months following the end of World War II,” citing the Pentagon Papers as the source.

The Supreme Court rules 6-to-3 against the government. Noting earlier rulings that “any system of prior restraints of expression comes to this court bearing a heavy presumption against its constitutional validity,” and that the government “thus carries a heavy burden of showing justification for the enforcement of such a restraint,” the Supreme Court says that the government’s case left that heavy burden unmet. The ruling frees newspapers to resume publishing.

The Supreme Court issues nine separate opinions, one by each justice, none of them commanding the support of a court majority. This leaves unsettled for the time being questions of whether, and under what conditions, the government may exercise prior restraint on a free press.

The 6-to-3 decision “shows what these superannuated fools like [Justice Hugo L.] Black and [Justice William O.] Douglas, what they do to the court,” Kissinger says. “Because with two more appointments—”

“Yeah, we’d’ve had it,” President Nixon says.

Kissinger informs Nixon that Ellsberg has given Sen. Charles M. “Mac” Mathias, R-Md., some Nixon administration documents from 1969, “a bundle of documents of [Secretary of State William P.] Rogers’ memos to us, and our replies.”

The President responds with alarm. “They have some NSC documents?” Nixon asks. “Now, we don’t have any on Cambodia in there, in the NSC, do we?”

Kissinger doesn’t know what the memos cover. “If they drive us too far, I think you ought to go on national television with a charge of treason, and say this is what they’ve brought us to, and now you’re going to fight your campaign to stamp this out. I really think you ought to get on the attack,” Kissinger says. “The government cannot run if this keeps up.”

President Nixon once again tells Attorney General Mitchell to disclose information gathered in the Justice Department’s investigation of the leak: “Don’t worry about [Ellsberg’s] trial, just get everything out. Try him in the press. Try him in the press. Everything, John, that there is on the investigation, get it out. Leak it out. I want to destroy him in the press. Is that clear? It just has to be done.”

“We’ve got to do this. Otherwise he’ll become a peacenik martyr,” Mitchell says

Chief of Staff Haldeman asks Defense Secretary Melvin R. Laird to send a colonel to Brookings to retrieve any classified material that might be in the think tank’s possession.

President Nixon demands a different approach. “I want them just to break in,” Nixon says. “Break in and take it out. You understand?”

“I don’t have any problems with breaking in,” Haldeman says. “It’s just in a Defense Department-approved security—”

“Just go in and take it. Go in. Go in around eight or nine o’clock,” Nixon says.

“And make an inspection of the safe,” Haldeman says.

“That’s right. You go in to inspect it, and I mean clean it out,” Nixon says.

Thursday, July 1, 1971

The New York Times, Washington Post, Boston Globe and St. Louis Post-Dispatch publish Pentagon Papers stories.

“The Pentagon’s secret study of the Vietnam war discloses that President Kennedy knew and approved of plans for the military coup d’état that overthrew President Ngo Dinh Diem in 1963,” the Times reports.

“The Times, to my great surprise, gave a hell of a wallop to the Kennedy thing,” President Nixon says.

The President moves forward with plans to fight potential leaks with leaks of his own. “We have to develop now a program, a program for leaking out information. For destroying these people in the papers,” Nixon says. “Let’s have a little fun.”

To fight the conspiracy he believes is out to get him, the president demands that his men take part in a real criminal conspiracy. “We’re up against an enemy. A conspiracy. They’re using any means. We are going to use any means. Is that clear? Did they get the Brookings Institute raided last night? No. Get it done. I want it done. I want the Brookings Institute safe cleaned out,” the president says. “Get on the Brookings thing right away. I’ve got to get that safe cracked over there.”

Shares