Is fake news a problem for American democracy? You bet! But is fake news the problem for American democracy? Not according to a study recently published by the Columbia Journalism Review, with the straightforward title “Don’t blame the election on fake news. Blame it on the media.”

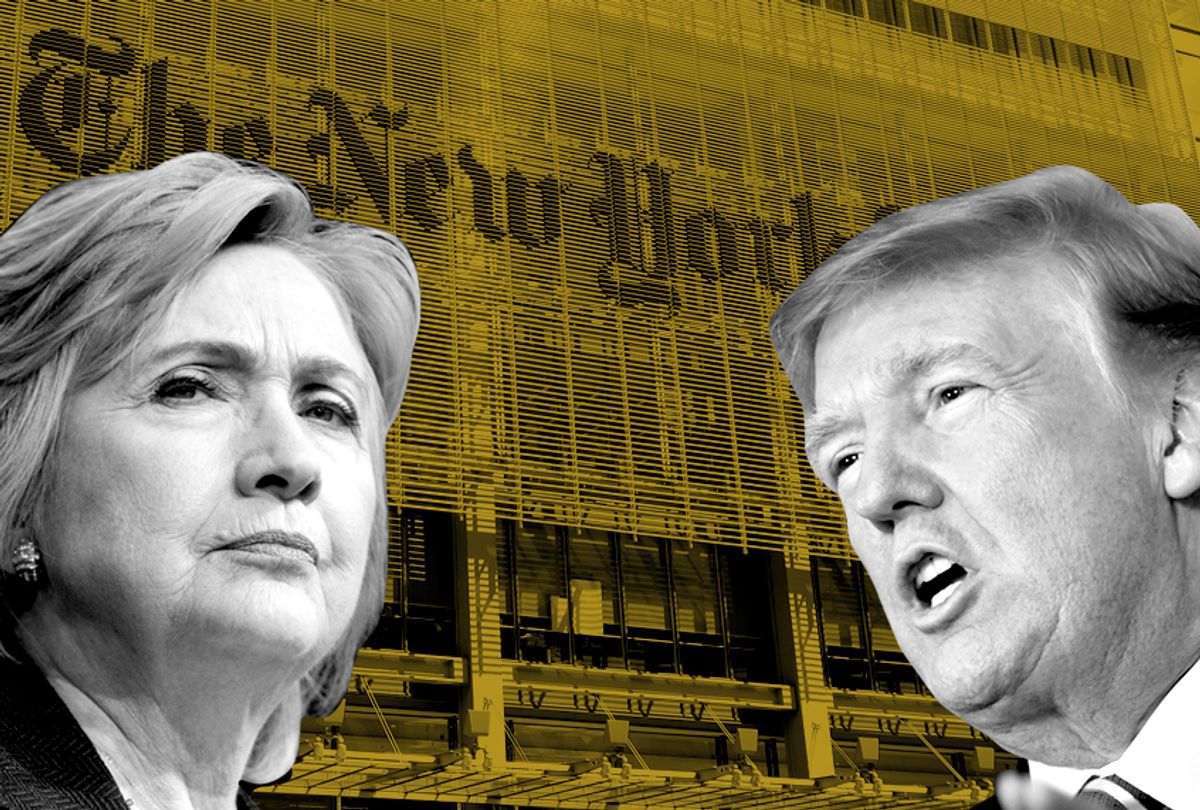

My takeaway from this study was simple: For all the unexpected impact that fake news had during the election -- which co-authors Duncan J. Watts and David M. Rothschild acknowledge -- and all the attention it’s gotten since, its overall impact was overshadowed by the sheer volume of stories coming from the established media. That was typified by the New York Times, which even in our widely dispersed media landscape still retains enormous agenda-setting clout. Everything matters in a close election, but that surely includes the media establishment itself, which has largely escaped serious self-reflection. That is desperately needed now.

“Our objective was not so much to apportion blame as it was to point out that the current blame game (fake news, Russian hackers, 'platforms,' etc.) just isn’t convincing when you look at the numbers in context,” Watts told Salon via email. “There was fake news out there, but it just wasn’t that prevalent when compared with real news.”

Take the example of the 3,000 Russian-funded Facebook ads paid for through fake accounts totaling more $100,000. That compares to daily ad revenues of $96 million in the fourth quarter of 2016 alone ($8.8 billion total) — a sum nearly a thousand times larger in just one day.

The authors refer to an earlier study that provides a useful framework for viewing their work: “Partisanship, Propaganda, and Disinformation: Online Media and the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election,” by a group of Harvard researchers led by Rob Faris. That one was an August followup to an earlier study headed by Yochai Benkler, which first exposed the extent of right-wing media influence. These Harvard studies revealed an asymmetrical media structure, dominated by the far right on one side and the center-left on the other. This big-picture structure helps explain the crucial narrative-mediating role played by the New York Times, which was the central focus of the research, even as right-wing sites like Breitbart eclipsed the influence of center-right outlets like the Wall Street Journal, and sometimes even Fox News.

The study analyzed the Times' coverage over the classic election period, from Sept. 1, 2016, through Election Day, using two data sets of election-related stories: the first containing 150 front-page stories, the second, 1,433 online articles. The stories were sorted into three categories, "Campaign Miscellaneous," "Personal/Scandal" and "Policy," with the second subdivided by candidate and Policy subdivided into four subcategories: stories with no details, stories focused on one or the other major-party nominee and stories focused on both of them.

Their findings were shocking: The Times was de facto strongly biased against Hillary Clinton and in favor of Donald Trump, simply by what the paper chose to focus on. For example, over one six-day period, the Times "ran as many cover stories about Hillary Clinton’s emails [10] as they did about all policy issues combined in the 69 days leading up to the election.”

Thus, it wasn’t just James Comey’s outrageous last-minute announcement about investigating Clinton’s emails on Anthony Weiner’s laptop that hurt Clinton’s campaign. It wasn’t just the 10 front-page stories the New York Times wrote about that. It was the combination of the Times’ saturation coverage of Clinton "scandals" with an almost total lack of covering substantive issues that put Clinton at a deep disadvantage that virtually no one seemed to recognize at the time — or even now, except for the authors of this study.

More broadly, Watts and Rothschild found:

Of the 150 front-page articles that discussed the campaign in some way, we classified slightly over half (80) as Campaign Miscellaneous. Slightly over a third (54) were Personal/Scandal, with 29 focused on Trump and 25 on Clinton. Finally, just over 10 percent (16) of articles discussed Policy, of which six had no details, four provided details on Trump’s policy only, one on Clinton’s policy only, and five made some comparison between the two candidates’ policies.

So, one Clinton policy story ran on page 1, compared to four for Trump — less than 1 percent of the Times' front-page coverage. If Clinton had a hard time getting her message out, she certainly didn’t get much help from the newspaper of record. She had better cause to call it “the failing New York Times” than Trump ever did. Even though Trump got slightly more front-page scandal coverage than Clinton did, he faced nothing remotely like the six-day avalanche she endured.

As for the second database:

The results for the full corpus were similar: Of the 1,433 articles that mentioned Trump or Clinton, 291 were devoted to scandals or other personal matters while only 70 mentioned policy, and of these only 60 mentioned any details of either candidate’s positions. In other words, comparing the two datasets, the number of Personal/Scandal stories for every Policy story ranged from 3.4 (for front-page stories) to 4.2. Further restricting to Policy stories that contained some detail about at least one candidate’s positions, these ratios rise to 5.5 and 4.85, respectively.

The focus on scandal and refusal to focus on policy combined with a more intense focus on Clinton's email scandal compared to the more diffuse coverage of Trump's — exactly the opposite of Trump and his supporters' endless “whataboutism” claims. Given how the Times is portraying itself now, nearly a year into the Trump administration, this report is particularly damning. Point fingers at “fake news” all you want, but take a good hard look in the mirror.

Summarizing the researchers' findings, Watts wrote:

The real news coverage was problematic in two ways: First, it focused on scandals and other entertainment themes (e.g., horse race) at the expense of policy differences (this was true both for the NYT and the Benkler, et al., analysis); and second, when the NYT did write about policy (e.g., Obamacare) they omitted critical information. So the argument was more about the “real” news letting people down, not that in doing so they necessarily threw the election (although the Comey incident was really bad …)

I asked Rob Faris, the Harvard researcher who led the earlier study mentioned above, for his thoughts about the new findings. He responded by email:

This new paper means that we now have three studies that use substantially different methods to address the same question that all produce essentially the same answer; coverage of scandals far surpassed coverage of policy issues. That provides validation for all three studies. In our study, we looked at a much broader set of media sources and found evidence that coverage of Clinton scandals was much higher than Trump scandals. This study, looking solely at the NYT, found more coverage of Trump scandals. These two findings are not contradictory. I agree with the authors that fake news is [a] problem but is frequently exaggerated and is not the most important issue.

To bring things into sharper focus, let’s take a closer look at Faris' study, “Partisanship, Propaganda, and Disinformation," and add some explanatory detail. His team examined both mainstream and social media election coverage, and reached the conclusion that the "structure and composition of media on the right and left are quite different":

The leading media on the right and left are rooted in different traditions and journalistic practices. On the conservative side, more attention was paid to pro-Trump, highly partisan media outlets. On the liberal side, by contrast, the center of gravity was made up largely of long-standing media organizations steeped in the traditions and practices of objective journalism.

This asymmetry reflects the larger cultural difference in American politics, described in Matt Grossmann and David Hopkins' book "Asymmetric Politics: Ideological Republicans and Group Interest Democrats" (Salon review here.)

“There is no question that Democrats are more accepting and trusting of the mainstream (nonpartisan) media's role in arbitrating disputes,” Grossmann told Salon, “which makes them less likely to rely on explicitly leftist or liberal media compared to Republicans." The 2016 election, he added, "saw an increase in questionable partisan media sources and Republicans seemed to more readily accept these sources."

Grossmann continued, “It is also true that the mainstream media reacts to conservative media critiques, sometimes by trying to balance coverage even when it is not justified or critique Democratic candidates more in response to conservative media stories. There is also a long history, he said, of “Clinton-specific media coverage that may be unrelated to conservative media,” but that cemented the widespread perception that Bill and Hillary Clinton have engaged in dubious or perhaps criminal activities. This goes back at least as far as the ultimately nonexistent Whitewater scandal, as described by Gene Lyons in his book "Fools for Scandal: How The Media Invented Whitewater."

In short, there were two sides playing two very different games. The dominant pull of partisanship on the right helped boost more extreme sites like Breitbart over more established ones like the Wall Street Journal. Things were starkly different on the left, as the Harvard report continues:

The institutional commitment to impartiality of media sources at the core of attention on the left meant that hyperpartisan, unreliable sources on the left did not receive the same amplification that equivalent sites on the right did. ... These same standard journalistic practices were successfully manipulated by media and activists on the right to inject anti-Clinton narratives into the mainstream media narrative.

This is the light in which I see Watts and Rothschild’s devastating observation about that six-day period when the Times ran as many cover stories about Clinton's emails as it ran about all policy issues, cumulatively, during the entire general election campaign.

In other words, despite the Times' profession of objectivity, the paper was effectively hacked by pro-Trump forces and produced wildly biased reporting, even independent of the notion of pursuing journalistic "balance" within individual stories. I asked Watts to comment on this interpretation.

“That’s an interesting hypothesis,” he responded, “and reminds me of similar critiques of Democrats in Congress (i.e., that they have been dragged to the right by an ever more extreme Republican Party). It could be true, but I can also think of alternative explanations. An obvious one is the one we mentioned: that the NYT, along with basically everyone, was assuming Hillary would win and didn’t want to look as if they had helped her, so they were (either consciously or unconsciously) tougher on her than on Trump.”

I agree: That’s part of what happened. But conservatives surely perceived that as well, and used that ingrained assumption in crafting their strategy to hack the Times along with the rest of the establishment media. Watts then raised a second explanation:

Another [hypothesis] is that liberal intellectual types (which describes most journalists) are much more worried than conservatives and anti-intellectuals about appearing to be unbiased, and so overcompensate. Neither of these is “hacking” per se, but either could produce a similar effect. In the end I have no idea, but I agree that it’s worth thinking about.

That’s exactly what I mean by employing the metaphor of hacking: The right uses Enlightenment values, practices and institutions to subvert and destroy those very values, practices and institutions. They are essentially hacking our culture.

One of the masterminds of what is often called "paleo-conservatism" — which is more or less ancestral to Steve Bannon's nationalist ideology — has another word for it, and an elaborate theory to boot. It’s an example of "fourth-generation warfare” or 4GW, a term coined by William Lind, a longtime associate of leading New Right strategist Paul Weyrich. Researcher Bruce Wilson discussed the idea with me last year. Lind introduced the concept in 1989 in predominantly military terms, as an explanation of how warfare had changed from the time of Napoleon to now. In our 2016 interview, Wilson explained it this way:

Lind anticipated the coming of an age of "non-trinitarian" warfare. In Clausewitz's famous construction on war, there's the government, the army and the population. Each have distinctly different functions, and there's little to no overlap. The army does the fighting, the government and population do not. In 4G warfare those categories you mention — war/peace, combatant/non-combatant — disappear.

Lind is also largely responsible for the notion of “political correctness” as a vast conspiratorial enterprise — a view Donald Trump appears to share — and he introduced both concepts in the same paper, arguing that "political correctness" and "multiculturalism" was a fourth-generation warfare attack on Western culture:

Starting in the mid-1960s, we have thrown away the values, morals, and standards that define traditional Western culture. In part, this has been driven by cultural radicals, people who hate our Judeo-Christian culture.

As is often typical of the conspiracy-obsessed, Lind takes his own inner demons and projects them outward onto others. The pro-Trump legions who railed against “political correctness” in the 2016 election were perhaps the most ambitious fourth-generation warriors in recent political history. The "hacking" of the New York Times, as described above, is a case in point.

I asked Wilson to comment. "I'd certainly agree," he replied, "that the architects of the 4GW plot have turned 'the values and institutions of liberal democracy against itself.'"

Gary North, the Christian Reconstructionist who has been another key architect of the 4GW plot (whether or not he has used that term), explicitly called for his revolutionary cadres to exploit the relative openness of democratic society in order to open a pathway toward Biblical theocracy:

We must use the doctrine of religious liberty to gain independence for Christian schools until we train up a generation of people who know that there is no religious neutrality, no neutral law, no neutral education, and no neutral civil government. Then they will get busy in constructing a Bible-based social, political and religious order which finally denies the religious liberty of the enemies of God.

The openness of liberal, pluralist democracy can be a fatal weakness, as the Weimar Republic of the 1930s discovered, because it protects the civil liberties of determined revolutionary minorities willing to use any and all tactics to undermine and overthrow democracy.

Such is the profound peril we face today. The media’s problems are inextricably connected with the broader crisis of democracy. Part of what’s needed to hold the line against authoritarianism is for journalists to understand that, and change their practices accordingly. Which means, in part, to confront and question a great deal of what they now take for granted — not just about how they do journalism individually and story-by-story, but also institutionally, at the enterprise level.

One avenue would be to refocus on journalists as citizens first, rather than professionals. It’s not that they should abandon professional standards, but rather that they should approach journalism as a civic duty, which requires a more engaged approach to getting the news that helps other citizens do the same.

This echoes a point Watts made about journalistic responsibility. “A point we make in the paper is that journalists have a tendency to see themselves as passive observers of events," he said, "whereas in reality they are active participants, at least inasmuch as the public perception of events is what matters. This misperception is understandable, and maybe doesn’t matter much at the level of individual stories, but it starts to add up over the course of many such stories. For example, the narrative of Clinton as untrustworthy was less about what any one article said than it was about the sheer volume and prominence of the whole series.”

Rob Faris was more cautious, saying that “media organizations that are committed to accurate and objective reporting should not waver from that core mission." The big question, he added, is "whether they can also mitigate the asymmetries in the current media landscape.”

One way to do that is to become more conscious about how stories are framed, and what the supposed facts they present actually mean. “If I could suggest one thing for journalists and citizens alike to always be asking," Watts said, it would be this:

When presented with a numerical fact (e.g., Russians bought $100,000 of fake ads on Facebook, the top 20 fake news stories got 8,700,000 shares, etc.), don’t just accept the argument that is being made (e.g., that this is a big number and you should be really worried about it). You should instead ask: Is this a big number? How does it compare with other relevant numbers? Should I be worried (or impressed or happy), or is this a big nothing-burger?

Numerical literacy, while crucial, is only one part of a much bigger picture. The media’s knee-jerk tendency to treat politics with “balance,” for example, assumes a symmetry that simply does not exist. It ignores clear and current evidence that Republicans in Congress are much more extreme than Democrats and historical evidence showing that Republicans have grown dramatically more conservative since 1980, while Northern Democrats have remained basically unchanged. It's only the total evaporation of white Southern Democrats (Doug Jones to the contrary!) that has made the party more liberal overall.

In short, I would argue that reality-based journalism is an idea whose time has come. Either that, or democracy itself may be an idea whose time has gone. If that happens, we can't blame fake news or the Russians. We will have no one to blame but ourselves.

Shares