The consensual first misstep in the Beatles’ career occurred the day after Christmas, 1967. In England, this is what is known as Boxing Day, when the postman and others in the service industries, however broadly defined, can expect to receive a present in a box — or they once could, anyway. It’s a big shopping day, a big post-Christmas sit-around-and-bask day, and an ideal day for some light television entertainment.

It was into that market that the Beatles wished to step as their once glorious 1967 campaign drew to a close. The year had begun with their release of the finest single we have, in “Penny Lane”/”Strawberry Fields Forever,” then reached a zeitgeist-bending high water mark in the early summer with "Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band." Later in that summer, manager Brian Epstein died.

Lacking their rudder, in a sense, at least insofar as outside-of-the-studio decisions went, the band attempted to regroup by making a film on their terms. Their first two cinematic forays, "A Hard Day’s Night" (1964) and "Help!" (1965) were largely steered by others, with the former managing to meld itself into a glorious piece of top-end, artful cinema, the other being far patchier and flawed, but esoteric and esoterically watchable. Give it another try sometime — it has aged well.

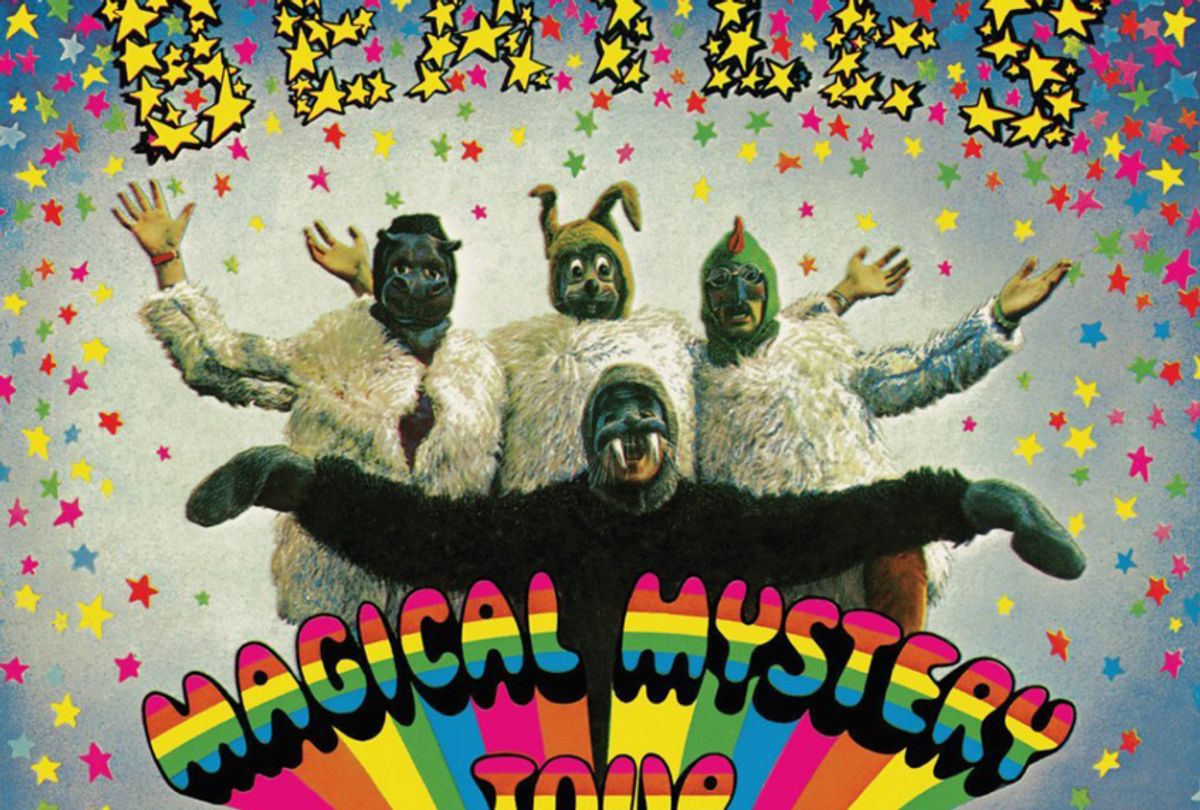

But then we have that first post-Epstein movie venture, "Magical Mystery Tour," the Boxing Day would-be treat that went way, way wrong. If you read any Beatles history that covers their entire career, you will encounter much condemnation of this film. I would venture that there are many critics who consider it the worst thing they ever did, and by a decent margin at that.

For a while, I didn’t watch it. I had some early screenings of the film, having been indoctrinated in the standard commentary about it, and that was enough for me. But seeing it again recently, and then a couple more times after that so as to make sure I hadn’t lost my own plot in terms of critical thinking, I couldn’t help but think this film is actually pretty damn ballsy -- pretty flawed, but there is real cinematic worthiness here.

One thing you can’t get around: This film starts the end of the Beatles. There is basically no script, with the Beatles deciding to, in effect, hire out a bus, put a bunch of people on it, zoom around the countryside, tape what were akin to several early music videos, and push John Lennon’s presence to the forefront of the film for some reason, even if it feels like Paul McCartney’s pet project.

McCartney was the auteur for this endeavor. He watched lots of surrealist films, was up to speed with the French New Wave, so think of him as the Liverpool student film version of Godard. All the Beatles get credit for directing, along with the unbilled Bernard Knowles, but this was McCartney’s progeny. He was a leader, for better or worse, with "Magical Mystery Tour" serving to rally the troops.

The Beatles must have thought they could have done no wrong, and it is not for nothing that I hear Lennon’s line of “And so it’s true pride comes before a fall” from “I’m a Loser” when I watch this production. But it’s invigoratingly relaxing, like the movie version of a joint, I suppose, and invigoratingly meta. And it’s bonkers funny, if you sit back and allow it to be.

For instance, we have Ringo Starr’s horrible acting chops. This is odd, because he was excellent in "A Hard Day’s Night." His post-hangover scene along that dreary trench, with the truancy boy, is as affecting as anything in the movie, perhaps because he was acting naturally — ha — on account of his real hangover, not really giving a toss how the scene played, which ended up making it feel more real.

In "Magical Mystery Tour," Ringo is on the coach with his recently widowed Aunt Jessie. He has some scripted lines, but you could not convince me that some of them are not made up on the spot, like when he starts busting her chops about her recently deceased husband. WTF Ringo?!

Even Aunt Jessie wants to crack up, it’s so out of nowhere. Later, Ringo is a wizard, because apparently it was important to have a group of these beings — played by Beatles, of course — oversee this oh-so-important bus trip. We are talking low, low-rent wizards. Ringo drops his magic wand, and they don’t even bother to reshoot the scene. Eh, just pick it up then, you wanker. And he does.

There are a lot of references to "A Hard Day’s Night." They are clever. One involves a Muzak version of “All My Loving” during a courtship scene for Ringo’s aunt, enacted on a beach. It’s a funny, druggily choreographed dance sequence. The conversion of Beatles songs to Muzak was intriguingly efficacious in lending gravity to the picture, making us feel that these people, so new upon the scene, were writers of standards, for it is normally standards that get the Muzak treatment.

It’s nice to play off of that in "Magical Mystery Tour," which also reprises Lennon’s “rule Britannia” quip from the bathtub sequence in "A Hard Day’s Night." He’s strong in this film, providing, for the first portion, anyway, narrative voiceover in a singsong voice with words that could have been sourced from his 1964 book of what we’ll call inspired nonsense, "In His Own Write."

Lennon’s speaking voice was like Orson Welles’: You don’t need him to sing the phone book, he could just read the names and you’d be transfixed. As we roll along, increasingly surreal versions of everyday events happen: a road race on foot that Ringo wins in a bus; a manic segment with an army recruiter; Aunt Jessie being fed shovelfuls of pasta. The placidity comes from the sensation of hanging out with these guys, like in a post-turkey-dinner haze, as you’re drifting off in your chair.

Visually, it’s a very passive film. What is curious, then, is that it’s anything but, when the music starts up. Consider, for instance, the “I Am the Walrus” sequence. It has been said that this is the Beatles’ most nonsensical song, but I hear it as the converse of that, a quite practical musical application of identity, what it means, how shifting it can be as we try to understand what ours is.

Ringo starts the action — and it is action — of this sequence with a rapid, violent, opening fill on his drum kit in a field. Apart from the race to catch the train — and evade fans — that begins "A Hard Day’s Night," this is the most energetic of all Beatles moments on film. Lennon looks like he was born just to execute his part, which is made all the better on account of the editing. The Beatles buzz about the frame, with varying degrees of costuming, alterations in how they wear that costuming, like Lennon’s head-wrap that makes of him, of course, an eggman. The animal masks the band don in this field provide something talismanic and Druidic. It’s creepy, bold, powerful, surging, a song with a chant that all but urges one to embrace one’s inner oddness.

The editing makes you wonder why they could do this, but not rein in other aspects of the film with a firmer touch. It all just kind of pools, flowing in one direction here, another there. You can have it on in the background for days, provided you have a firm enough grasp on reality that you, too, don’t flow down the drain and into the soft, almost washed-out colors of this film.

But the British public threw a hissy fit. The Beatles, essentially, had to apologize for foisting this on everyone. McCartney blamed it on the band being new to making their own films, which was true enough. The backlash, though, was more about their temerity in thinking that, hey hey, we’re the Beatles, people love everything we do!

But I don’t think they thought that. You know how it is when you’re a teenager, and you’re figuring out who you are, and you kind of let sides of yourself show that you would not have before? That’s what the Beatles, in my view, were doing here, now that they were “grown up” — that is, on their own, sans Epstein.

This film was the dreamy, druggy, indulgent portion of their post-Pepper id. I like that it had free rein. Next would come bigger things — like the White Album — that I’m not sure they would have had the confidence to do if they hadn’t struck out on their own like this and survived, shape-shifting pornographic priestesses of the British plains and rural motorways.

Shares