There is growing concern that the world’s oceans are in crisis because of climate change, overfishing, pollution and other stresses. One response is creating marine protected areas, or ocean parks, to conserve sea life and key habitats that support it, such as coral reefs.

In 2000, marine protected areas covered just 0.7 percent of the world’s oceans. Today 6.4 percent of the oceans are protected – about 9 million square miles. In 2010, 196 countries set a goal of protecting 10 percent of the world’s oceans by 2020.

Ocean parks that are very large and often remote account for most recent progress toward this goal, but they also are controversial. Some ecologists view them as the most effective way to protect ecosystems, deep-sea and open ocean habitats and large, highly migratory species. Critics say they may divert attention from conservation priorities closer to more densely populated areas, and are hard to monitor and enforce. And social scientists have questioned whether protecting such large zones infringes on indigenous people’s rights.

Our research seeks to inform conservation policies that are effective, equitable and socially just. In our new study of established or proposed large marine protected areas in Bermuda, Rapa Nui (Easter Island), Palau, Kiribati and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands and Guam, we show that efforts to protect even remote sites can generate important outcomes for local residents that they may view as positive or negative. They can increase national pride and political leverage for indigenous populations, for example. They can also complicate international conservation negotiations or cause broad shifts in national economies.

Here we discuss the Palau National Marine Sanctuary, one of the world’s largest, which was created in 2015. This sanctuary illustrates how large-scale ocean conservation has the potential to produce important social benefits.

Rebecca Gruby, CC BY-ND

Palau’s strategy

Palau is a small nation spread across several hundred islands in the western Pacific. As with many Pacific Island nations, Palau’s offshore tuna fishery is dominated by foreign vessels. Most of the revenues and fish that it produces are exported overseas. Only a small portion of the lowest-graded tuna makes it to Palau’s domestic market. At the same time, demand for seafood from Palau’s growing tourist industry is stressing other fish species in nearshore reefs.

In 2016, 136,572 tourists visited Palau – almost eight times the resident population. Palau is struggling to balance increasing tourist demand for seafood with the needs of local residents, who depend on reef fish for about 90 percent of their fish intake.

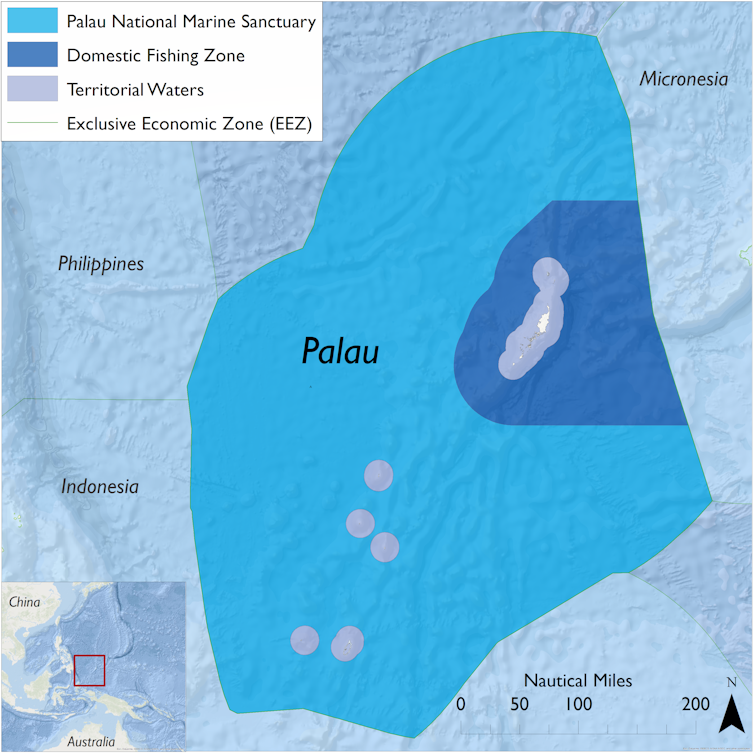

As part of a sweeping conservation and development vision, the sanctuary designates 80 percent of Palau’s exclusive economic zone (defined in international law as waters extending from 12 up to 200 miles off its coastlines) as a no-take reserve, and the rest as a domestic fishing zone. Virtually all of the fish caught in this zone must be sold in Palau. Fishing in the no-take reserve will decline incrementally and end by 2020. Palau’s territorial, or coastal, waters lie outside the sanctuary boundaries, but are protected by other policies like the Protected Areas Network.

Luke Fairbanks; data from from marineregions.org, protectedplanet.net, ESRI., CC BY-ND

This design seeks to protect marine species by eliminating foreign commercial fishing in most of Palau’s waters, while developing a domestic fishing industry that supplies local markets with large open-ocean species like tuna. By shifting more consumption to these fish, it aims to reduce pressure on reef fisheries near shore. And by spotlighting these actions as part of a shift toward high-end tourism, it seeks to promote sustainable economic development.

As Palau’s President Tommy E. Remengesau Jr. summarized, “The true purpose of the Palau National Marine Sanctuary is to protect our resources for our people.”

Who benefits?

Translating these goals into action has triggered social changes within Palau. Sanctuary managers and nongovernment organizations are raising funds to provide more local fishermen with the midrange fishing vessels and capacity they need to access fish in the offshore domestic fishing zone. Many local fishermen are eager for this new livelihood source.

Palau’s government has drafted legislation and developed marketing campaigns that feature Palau’s conservation commitments. It is also increasing visitor fees and asking tourists to sign a Palau Pledge upon arrival, in which they promise to act in an environmentally and culturally responsible way during their stay.

While critics argue this strategy will do more for “rich tourists” than for conservation, we believe such assessments are premature. The goal is to limit the number of toilets flushing, divers on reefs and reef fish being eaten, while increasing revenue through higher returns from fewer visitors.

Not everyone in the tourism industry supports these changes. But models suggest that they can enable Palau to meet future seafood demand while protecting its marine resources.

Importantly, we have seen no evidence that these changes will restrict local residents’ access to the spaces and resources they currently use. The domestic fishing zone is designed to give Palauans more access to fish in their waters. And Palau’s leaders have historically protected local access to the 445 Rock Islands – the primary destination for visitors – by designating only a small number for tourist use.

Linking offshore ocean protection to tradition

The marine sanctuary is also changing the way in which many Palauans relate to offshore ocean space. Palau’s council of highest ranking traditional leaders has enacted a customary law called a “bul” to protect the sanctuary through traditional protocols. A bul is conventionally used on land or in nearshore marine areas.

A member of Palau’s Council of Chiefs, which advises the president, told us that this is the first time traditional leaders have issued a bul in an offshore ocean area. This move has been controversial, but according to many of our interviewees, it grants the sanctuary a culturally important seal of approval and embeds offshore conservation within traditional knowledge and governance systems.

Of course, not all Palauans support the sanctuary. Some think the domestic fishing zone is too small, while others question how much protection the sanctuary actually offers for highly migratory open-ocean fish. Still others worry about possible lost fishing revenue or the impact of increasing visitor fees.

Important questions remain about how Palau will effectively and ethically address illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing. This problem is a critical global challenge, and Palau has been both applauded and criticized for contesting it aggressively.

Future research should examine how these social changes unfold. So far, the evidence suggests that Palau’s sanctuary has potential to deliver both conservation and development gains.

Government of the Republic of Palau via AP

Defining a new field

Palau’s sanctuary is one example of a new global phenomenon. But the race to create large ocean parks has outpaced science. Managers, along with biophysical and social scientists, are scrambling to answer questions about how well they work and who they benefit or harm.

Decades of research on smaller marine protected areas shows that they have to meet both biological and social goals to succeed. Now, more researchers are examining human dimensions across a number of large marine protected areas. Scientists can inform these conservation efforts by weighing evidence carefully in assessing how and why large ocean parks matter for people as well as for sea life.

Rebecca Gruby, Assistant Professor, Department of Human Dimensions of Natural Resources, Colorado State University; Lisa Campbell, Professor of Marine Affairs and Policy,Duke University; Luke Fairbanks, Research Associate,Duke University, and Noella Gray, Associate Professor of Geography, University of Guelph

Shares