I’m in Tennessee visiting my family for the holidays. I lived here until a few years ago, on a chicken farm only a mile or so from where I sit writing this. The farm is gone now; the family has moved closer to town, but my memory of the years we spent there is strong.

In fact, that’s me in the photograph, feeding the chickens one afternoon. And yes, that’s a smile of pride brightening my aging visage. The truth is, I loved those chickens. We averaged about 200 of them every year, eight or ten different breeds who laid eggs in about seven different colors: white, brown, blue, green, olive, pink and a deep mahogany the color of a CEO’s desk. We sold them to a local organic food place in Nashville called the Turnip Truck. Our eggs flew off the shelves. One reason: Parents snapped them up because kids loved to pick out their own special eggs in the morning. Plus, they were actually good for you.

The chickens lived in two chicken houses I built, one of them on an old steel trailer I traded for a .22 Luger pistol over in Murfreesboro. Our two flocks had the run of about three acres around the house. They would gallop down the ramps out of the chicken houses in the morning just after dawn, when the ground was still wet with dew, and immediately start pecking at worms that had emerged overnight. Then it was off to the races, eating-wise. Caterpillars, seeds, ticks, mosquitoes, the occasional butterfly and even a nice fat lizard every once in a while. Then at dusk both flocks would make their way back to their chicken houses and we would lock them up for the night against predators. Same thing all over again the next morning, and the next and the next and the next.

It was a farm, and they weren’t pets; they were livestock. But we loved those chickens, and it hurt when a hawk or a fox or a coyote would take one of them, leaving a pile of feathers where once a proud hen had strode the land. We would replenish the flocks once a year with a shipment of new chicks from a supplier out in Iowa, and raise them up and introduce them into the flocks, and our lives and their lives would go on. Legions of words have been marched across the page over the years describing life on the farm . . . the seasons . . . the animals . . . the backbreaking labor . . . the thrill of new life and the heartbreak when lives are lost. I can attest that every single word ever written about farming is true. You love it and hate it in equal measure, but one thing is for sure. A farm replenishes you every single day like almost nothing else on the earth.

We took an oath right from the beginning that we would follow the law of the farm and not get too close to our chickens, because we knew we would lose some of them and moving on would be necessary. For a long time, we followed that rule absolutely.

Then, late one afternoon on a cold February day, I was standing at the kitchen sink slicing vegetables for dinner when something caught my eye. There were three windows in the kitchen: one above the sink, one in the back door and one in the kitchen breakfast nook. I leaned over the sink and took a good look out the window. There were always chickens in the side yard, and I didn’t want to be day-dreaming if a hawk or coyote were menacing the flock. But there were no signs of a predator. The chickens were pecking away; the roosters weren’t sounding off; the peacocks were sashaying around showing off and not announcing a threat with their incredible fog-horn voices. I went back to slicing.

There it was again! A flash of something caught my eye. I looked out the window. Didn’t see a thing. Again! I saw it again! OK, I thought. I’m not imagining things. I stood there at the sink and turned my head so I could see it plainly, whatever it was. And then I saw her. A chicken was sitting on the top fence rail just to the right of the kitchen door and she was jumping up, flapping her wings wildly, then landing atop the fence. She did it again! And this time I saw that she had her head turned and she was looking in the window. She did it again! I tried to force the thought from my mind . . . she was a chicken after all . . . but it was obvious she was trying to get my attention.

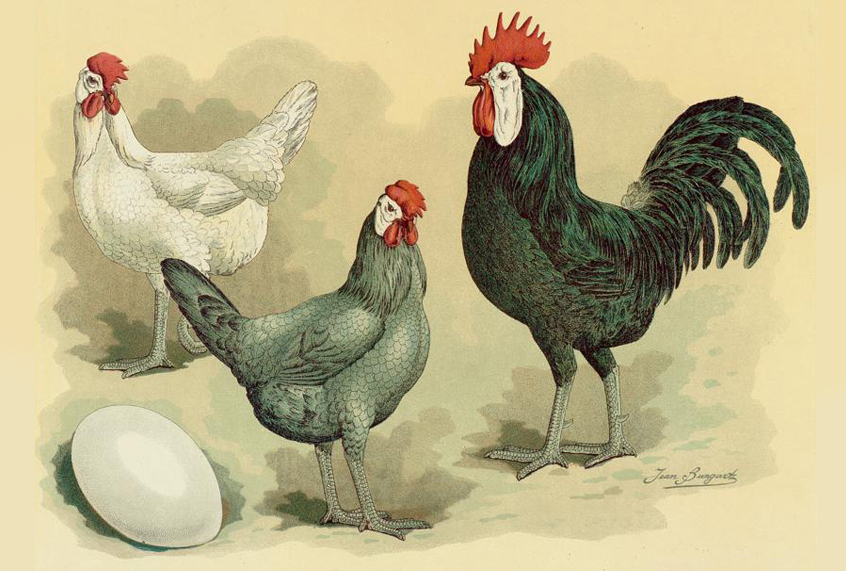

So I walked around the counter and opened the back door. It was a White-Faced Black Spanish, quite a regal black bird with a flash of white on either side of her head. When she spied me at the open door, she immediately flew down off the fence and marched straight over and hopped up the back steps and walked right past me into the kitchen, clucking softly to herself. She walked a few feet into the kitchen and spread her wings and fluffed her feathers and looked straight up at me, clucking. I walked over and picked her up and held her under my left arm and stroked the back of her neck.

“What are you doing in here, big chicken?” I asked stupidly.

She clucked and I could feel her muscles relax under my arm. I grabbed a kitchen towel and walked into the living room where the news was purring on the TV. Sitting down on the couch, I spread the towel across my lap (chickens have a habit of depositing poop wherever they are, including your lap, so it’s necessary to protect yourself). She didn’t hesitate for a second. She thrust her legs straight out behind her and lay herself out, extending her neck across my right thigh, and she went right to sleep.

I don’t know how long I sat there like that, stroking the back of her neck. I was astounded, struggling to wrap my head around the behavior of this gorgeous black chicken. It was as if she knew exactly what she was doing . . . as if she had a plan or something . . . and now she was where she wanted to be. Not outside in frigid February weather, but inside, on my lap, comfortably warm and sound asleep.

After a while the kids came downstairs and saw me sitting there with her. No chicken had ever behaved like that before. It was charming and wonderful in a way that’s hard to express. And it definitely wasn’t farming. Then the kids got hungry, and I had to pick her up and carry her outside and put her back down among the flock and get back to cooking supper.

You can no doubt guess what happened the next afternoon. Same thing. Big Chicken — yes, our whole farm-rules thing fell apart and we named her — jumping up from the fence, looking in the window. Me opening the door, she marching in, clucking and fluffing. Me picking her up and carrying her into the living room. She going to sleep on my lap.

This went on for a couple of days, and then one afternoon I went out to get in the car and drive down to the end of our private road to pick up the kids from the school bus. Big Chicken was waiting for me and jumped into the front seat of the car and quickly took a spot in the passenger foot well. She rode down to the corner with me, I parked and picked her up, and together we waited for the bus. When the kids got in, she happily took her place on the floor and we drove back to the house, parked, and we all got out. Big Chicken included.

Our little journey to the corner together continued for I don’t recall how long — maybe a couple of weeks. So did our sojourn on the sofa every evening: Big Chicken happily snoozing on my lap, me watching talking heads babbling on MSNBC. Then one afternoon, Big Chicken wasn’t outside the window jumping up and down. I went outside and looked around for her but couldn’t find her anywhere. Maybe she was just hungry, still pecking away for food. Next day, same thing: no Big Chicken.

We knew what happened. Big Chicken was among the breeds who like to sleep up in trees at night. Rare breed chickens are way smaller and lighter than conventional American chickens, the kind you see pictured on egg cartons. They can fly for short distances and they can reach the lower branches of trees where they perch for the night. Only one problem: owls. We had lost tree-perching chickens to owls before, and so it was that we lost Big Chicken. I have to tell you, it was heartbreaking. That chicken was something to behold, and her behavior was so out there, you couldn’t help but love her. We never found her body or even a pile of feathers, which wasn’t uncommon with owls. They would often carry off their prey and have their meal somewhere else. But we never forgot Big Chicken, the hen who caused us to break our farmers’ pledge and drop our guards and take her as a pet.

I don’t think about Big Chicken all the time, but the memory of her came to me recently as I was contemplating our behavior as boys and girls, men and women — even those of us who are older men and older women. Isn’t that a bit like what we do? Jump up in the air and fluff our feathers, trying to get each other’s attention? Isn’t that what we were doing, really, when we walked down a school hallway gazing longingly at the gorgeous girl standing at her locker or the cute guy hanging out on the steps of the A Building? Didn’t we look down the bar on a winter night and see each other and long to be in each other’s arms on a nice comfortable sofa? Isn’t what we’re doing online, jumping up and down and trying to get a look through each other’s windows? Laptop screen, smartphone, tablet — it’s all glass, all windows into worlds we would rather be in than the one we’re stuck in.

Isn’t that what we all want? To be Big Chicken? To be taken inside where it’s warm and cozy and to lean our heads on another’s shoulder? Could it be true that we haven’t evolved much beyond a White-Faced Black Spanish hen on a Tennessee chicken farm? And really, isn’t that quite wonderful?

I’m a retired chicken farmer, and that’s what I think.