It was a sunny afternoon in 1995, a week after the Oklahoma City bombing, during the brief period that Dad knew Timothy McVeigh only as America’s most hated man, and nothing more.

A baby had been found buried in the rubble of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building after seven days, the media reported. Her last name was Coyne, like mine, and she was soiled in blood and soot and shit. She was 14 months old, five months my junior. Our mothers, who never met, both worked at courthouses in downtown Oklahoma City. I attended day care in Norman, the nearby college town where Dad taught at the law school. She was in the Murrah building’s nursery across the street from her mom’s office when McVeigh’s bomb went off. Any connection I shared with the dead little girl was, by all accounts, an unremarkable coincidence.

When Dad realized why the reporter simpering lukewarm condolences had called our house, he yanked our answering machine straight from the wall. The bastard had probably found our number in the white pages and mistaken our family for the little girl’s, Dad guessed. Or perhaps he’d simply called every Coyne in the book, for good measure. How callous, how cruel, turning tragedy into pity porn. Dad considered, for a moment, giving the reporter the sound bite he deserved, but as he thought of his own daughter, safe in the next room, a sick sadness overcame him. It didn’t matter anyway; the message cut off before the reporter gave his contact information.

One of Dad’s former law students from his capital punishment class, Jim Hankins, called three weeks after Dad reinstalled our answering machine. Now a bona fide member of the bar, Jim worked for a firm called Jones & Wyatt in Enid, Oklahoma. It was no secret the firm had a notorious new client, and the government wanted him dead. Dad, Oklahoma’s premier capital punishment scholar, could really help out, Jim said.

That’s how Dad became one of Timothy McVeigh’s lawyers. And that’s when Timothy McVeigh — the scrawny kid with blood vengeance and a buzz cut, the man who murdered Jaci Coyne — became Tim.

* * *

In total, Tim killed 169 people. Nineteen of them were children. The Oklahoma City bombing remains the deadliest act of domestic terrorism to this day. It surprises me how many people my age don’t know that. I guess I can’t blame my peers; I don’t remember the bombing either.

My generation was the first to grow up under the threat of modern terror, taught to hide in bathroom stalls and crouch atop toilets so school shooters wouldn’t spy our sneakers. Our growth spurts and awkward phases have been documented in Transportation Security Administration-mandated full-body renderings.

The Oklahoma City bombing eludes me, though. I was 19 months old when the Alfred P. Murrah building exploded, 2 and a half years old when Tim’s trial began, 7 years old when he withdrew his appeal and accepted his death sentence, and nearly 8 years old when he died with his eyes wide open. By then I had grown into someone who could grapple with death. How could I miss that?

There’s a scene in “The Princess Bride” where Inigo Montoya, the Spanish swordsman; Fezzik, the gentle giant; and Westley, the farm boy turned pirate, crouch behind a balcony, overlooking the swarm of men guarding Prince Humperdinck’s castle. Westley, who spent the day mostly dead, has just regained consciousness. “Who are you? Are we enemies? Why am I on this wall? Where is Buttercup?” he asks with feverish confusion.

“Let me explain,” Inigo says, then pauses. “No, there’s too much. Let me sum up: Buttercup is to marry Humperdinck in a little less than half an hour. So all we have to do is get in, break up the wedding, steal the princess and make our escape . . . after I kill Count Rugen.”

“That doesn’t leave much time for dillydallying,” Westley says.

Like Westley, I must rely on others to fill me in on what I have missed. My parents’ stories are at once plentiful and sparse, overwhelming and inadequate. I lose myself in questions. I succumb to nightmarish imagination. I haven’t figured out how to mourn what I can’t remember.

After I was born, Dad designed a set of personalized trading cards. A lifelong Red Sox fan, he distributed the novelty to family and friends, noting the potential value of a Marley Coyne original, collector’s edition.

On the front of the card sits me, in the mushroom cloud of my diaper, hoisting a yellow building block like a World Series trophy. The back of the card read:

Marley B. Coyne: Peripatetic Prodigy. Ms. Coyne is an accomplished literary critic who enthusiastically recommends Pat the Bunny, Goodnight Moon and The Itsy Bitsy Spider. She speaks fluent Duck and delights in toppling tall stacks of building blocks. Her favorite pastimes: prattling and perambulation.

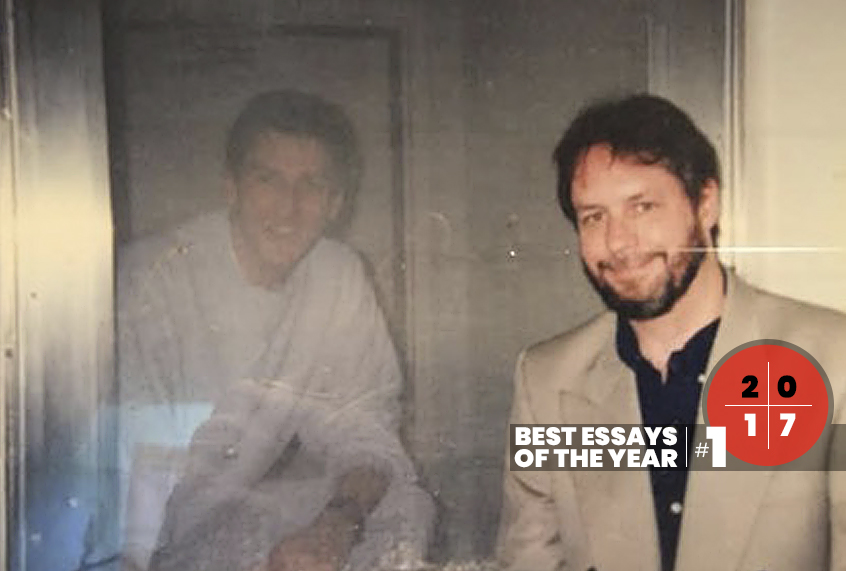

Dad gave a copy of the card to Tim when he first met him, six weeks after the bombing. Tim stared at the picture of my chubby face, then flipped it. “Oh, you meant business card!” Dad said. If Tim betrayed any emotion, it was placid bemusement. Dad took back my card and reached in his breast pocket for the business card Tim wanted. “Just a joke,” he added.

* * *

“He wasn’t very old. I don’t think he’d had much sex,” Dad told me over FaceTime. “He was shy and goofy and tall and awkward and disillusioned and immature and angry. He was all those things.”

I was a senior in college, writing about how the Oklahoma City bombing affected my family for my thesis. As it happened, the piece was due on April 19, 2016, the tragedy’s 21st anniversary. It felt right, necessary even, to end my formal education learning this story and telling it in my own way. I have never worked harder than I did on this project.

My parents answered my questions with caution, but they did answer them. Together we stifled the obvious horror of it all — the blood, so much blood, children’s blood — and looked inward. Dad told me the case “fucked things up pretty good” for him. He apologized, too often, for a hell I don’t remember. I failed to convince him of my forgiveness. Mom warned me to not get lost in the depths that nearly swallowed him. I couldn’t resist.

Dad shared photographs and anecdotes as if Tim were a troubled friend he had lost touch with after adolescence. He told me how Tim once sent me an episode of “Barney & Friends” on VHS. Tim knew Dad hated the singing, dancing dinosaur so much he banned the show from our house. It was just Tim’s little joke — using me to needle Dad.

Dad discarded the video, but he gave me a birthday card Tim wrote — official prison mail, resealed and government stamped — behind Mom’s back. “To honor Tim’s good gesture,” he said. That was the kind of rapport they had.

* * *

If Dad remembers correctly, I spoke to Tim just once. I was maybe 6. I answered his collect call from the Terre Haute United States Penitentiary on Christmas morning. We talked about Santa Claus.

“How did he deal with that? Talking to a child when he killed so many?” I asked.

“I don’t think he ever did,” Dad said. “Whenever we talked about the 19 children in the day care center, a wall just went up. I don’t think he could allow himself to even think about it because it would have crushed him — the horror of what he’d done.”

I scanned the pixelated image: Dad sitting on the couch in a room I once knew; his mutt, whose fleas we used to pick, wagging her tail in and out of the frame.

“I think it was really a boost for him.” Dad said finally. “Just to hear a little kid’s voice talking about the wonder of Christmas.”

I have never experienced a strangeness comparable to knowing that I once brought a mass murderer something close to happiness. I made Timothy McVeigh’s Christmas.

* * *

I won’t linger on the trial — the scandals and incompetence, the devastating run-ins with the victims’ families, the friendship Dad built with the man who had annihilated their loved ones, the animosity he and Tim harbored towards the case’s lead attorney. Dad left the case officially, after Tim was sentenced to death, but he agreed to help Tim pro bono get his will and other affairs in order. He remained his ally and confidant until the end.

I should mention: I have always been frantically protective of my father, though I have often felt powerless to defend him. Once at a gathering of colleagues and friends, and after what I’m sure was more than a couple of beers, Dad and one of his buddies decided to wrestle on the living room floor for the amusement of the crowd. I was a toddler curious about the source of excitement. To my dismay, I saw a man pinning my dad, who in turn was trying to grip his attacker in a headlock. I ran forward, shaking my inchworm of an index finger at the villainous stranger and cried, “Don’t hurt my Daddy!” The crowd laughed hysterically. I was quite serious.

After months of living in Denver and flying back on the occasional weekend, Dad returned to Mom and me and a life in Norman. He brought Tim home with him, too.

Dad balanced chores, like picking me up from day care, with errands, like mailing porn and books on anarchy to Tim. He took Tim’s sister out for Thai with Mom and me, “the girls.” He promised to smuggle Tim’s ashes into Giza and spread them at the base of the pyramids. He sent love letters and presents on Tim’s behalf. He handled all the minutiae that accompanies a death sentence.

Eventually Dad cracked.

The thing about the Oklahoma City bombing is that it follows you. At least, it follows Dad. A week after he returned home from the trial in Denver, he wrote in his trial journal, “Readjustment is incredibly painful for everyone. I hate myself for the damage I have done to my girls.”

As I said, I don’t remember much. But one memory sticks while the rest wither in oblivion. I was in the music room, surrounded by wall-to-wall bookshelves, packed with thick legal tomes. Tim smiled down at me from a framed photo atop the Yamaha piano that was Dad’s homecoming present. I was wearing a black velvet dress with silver stripes and an Empire waist bow. Dad swears he was sober that day; I remember he reeked of skunk and stale bread.

Dad wanted to take me with him to the Laundromat, and Grandma, who was helping Mom care for me, said no. He screamed at her. She screamed back. I felt oddly aware of my stature, my childishness. I watched the vitriol soar above my head. At some point, Dad pulled me to his side of the room and, in his fury, ripped the bow off my favorite dress. Quiet fell. The angry faces I didn’t recognize became familiar again. Dad — my daddy — asked me what I wanted.

In the car, I shuffled through the glove compartment and checked under the seats for spare quarters to feed the machines. Of course, I chose to go with him.

* * *

One night in the spring of 1998 while sitting on our front porch, head in her hands, wondering how she was going to shield me from her husband’s self-destruction, Mom swore she saw God. It felt as if someone were holding her in a blanket of sunshine in the middle of a cold night. I vividly remember her telling me this because I’ve carried that image with me every day since.

Dad had stopped showing up to teach his death penalty classes. He picked fights with the dean of the law school. He forgot to pay bills. He beat his drums so hard he nearly rendered himself arthritic. He screamed and thrust his finger in Mom’s face. He drank and drank and wrote letters to Tim.

On that night, Mom had discovered Dad was hiding a gun in his music studio. When either divine intervention or exhausted delusion returned her to the ground, she decided to divorce him.

* * *

Today, Dad is more or less retired. He focuses full-time on drumming, his first passion. (Before going to law school, he had taught high school band.) Pummeling his Yamaha kit at Chinese restaurants and Lutheran churches across Oklahoma helps him abate the nightmares filled with autopsied corpses rising from rigor mortis. He hasn’t had a drink in 18 years, and I’m so proud of him.

Dad also lives his life like he is on death row. He doesn’t go to the doctor as often as he should. His friends tend to die gruesome, premature deaths. On his iPhone, he keeps a playlist of songs to play at his funeral.

At least once a year, he reminds me to sell everything he owns after he dies. “I have Tim’s old Army fatigues, all his medals. . . . There are some crazies out there who would pay a good deal of money for that kind of thing. Just don’t throw it all out,” he says.

I dread the day I’ll have to sort through boxes of Tim’s fatigues and other remnants of Dad’s life to divide into keep, sell and toss piles. This is my inheritance, to pass on to the highest bidder. I want to feel liberated when I finally discard the man who has haunted us for 22 years. I want to find comfort knowing what remains of him will rot in the back of someone else’s closet. I want it to be that simple, but it’s not. I’m afraid the day my father dies, Tim will come to collect him. I’m afraid he will one day steal my daddy for good.