Arthur Miller once said that what separates the great artists from their merely proficient peers is not talent, intelligence, or dedication, but an “unquenchable moral thirst.”

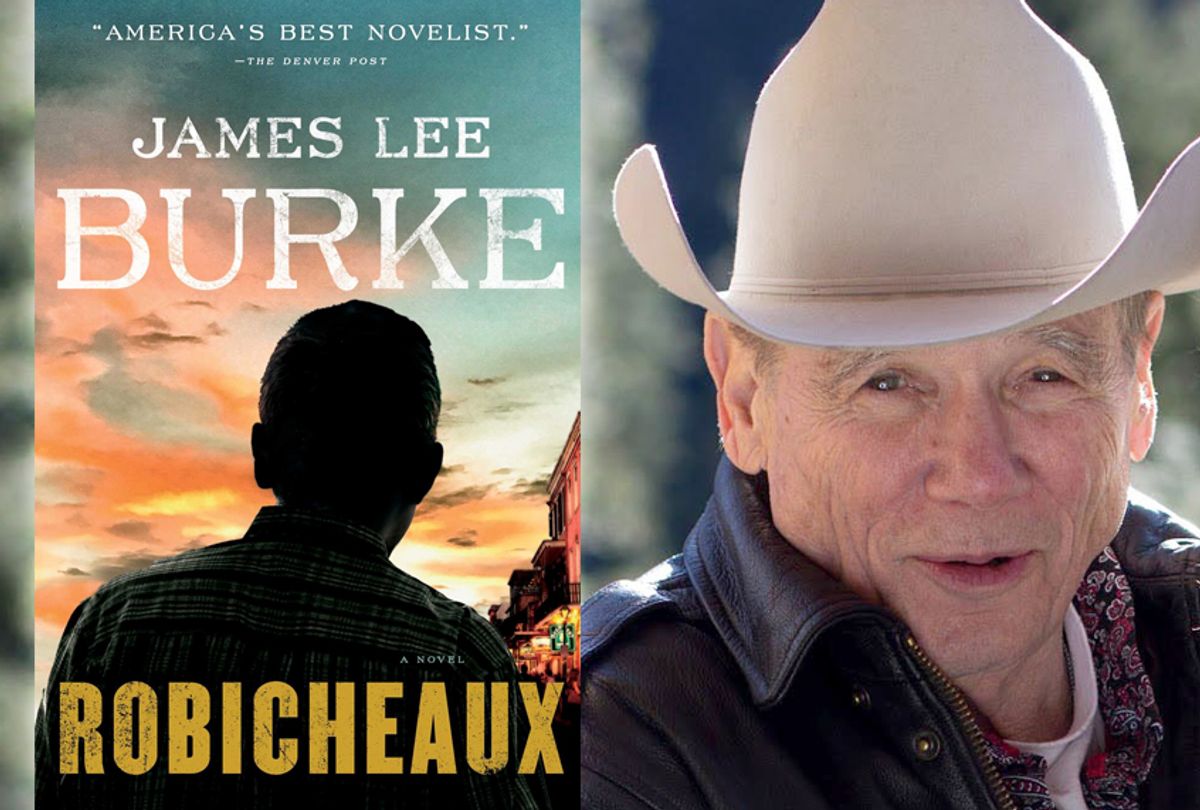

If the late playwright was correct, then his insight serves as explanation for why and how James Lee Burke, one of America’s best novelists, continues to write profound, poetic and important books at the age of 81, after already having won two Edgar Awards — the most prestigious honor for crime writers -- a Guggenheim fellowship, and a nomination for the Pulitzer Prize. Burke infuses into his art a theological treatment of ethics, allowing for acts against humanity — both of the smallest repute and the largest consequence — to crack open the essence of reality in contemporary America, but also resting in what Poe famously called, “the tell-tale heart.”

In his new novel "Robicheaux," Burke takes readers back to the bayou where his most beloved characters reside: David Robicheaux, a sheriff’s deputy in New Iberia, Louisiana, and his best friend, a private investigator named Clete Purcel, whom Robicheaux describes as the “noblest man” he ever knew, and also the “libidinous trickster from folklore.”

Robicheaux is a three-time widower, recovering alcoholic and Vietnam combat veteran whose ironclad commitment to justice makes his antecedents not so much Sherlock Holmes and C. Auguste Dupin but the heroes of myths and epics. The first series of Robicheaux novels, Burke has claimed, was his attempt to recreate John Milton’s "Paradise Lost" trilogy in a modern setting by casting a noir-ish neon shadow over the ancient struggle between good and evil.

Raymond Chandler likened the honorable detective, crusading for justice through city streets and alleys, to the medieval knight on horseback.

There can be no doubt that the time for America to welcome back a heroic warrior, even a literary one, is now. Burke does not disappoint. He has performed a magic trick possible to only the most imaginative and substantive of writers. He has written a book that is topical, but timeless.

One of the villains in “Robicheaux” is Jimmy Nightingale. His biography should sound familiar to anyone minimally lucid over the past two years. Nightingale is a real estate developer and owner of casinos whose celebrity has allowed him to enter politics as a demagogue. Running for an open senate seat in Louisiana, he has excited large, working-class audiences like few other candidates of modern times, but he also maintains connections with white nationalists, including Bobby Earl (who is a dead ringer for David Duke), and battles accusations of sexual assault.

Burke, in the voice of his protagonist, describes a Nightingale rally, and those who animate it with their convulsive outbursts, with a perfect balance between empathy and horror. It is likely the most accurate description of the Trump phenomenon and coalition in print:

The Cajun Dome was overflowing. Jimmy walked onto the stage ten minutes late in a white suit and cordovan boots and a dark blue shirt open at the collar, a short-brim pearl-gray Stetson gripped in his hand, as though he hadn’t had time to hang it. The crowd went wild. In front, some rose to their feet. Then the entire auditorium rose, stomping their feet and pounding the backs of the seats with such violence that the walls shook.

I thought of Hitler’s arrivals, the deliberate delay, the trimotor silver-sided Junkers droning in the distance from afar and then appearing in the searchlights like a mythic winged creature descending from Olympus…

Nightingale’s adherents wore baseball caps a T-shirts and tennis shoes and dresses made in Thailand. They were the bravest people on earth, bar none. They got incinerated in oil-well blowouts, crippled by tongs and chains on the drill floor, and hit by lighting laying pipe in a swamp in the middle of an electric storm, and they did it all without complaint. If you wanted to win a revolution, this was the bunch to get on your side. The same could be said if you wanted to throw the Constitution into the trash can.

Nightingale is entangled in a web of sadists, misanthropes and con artists who, for complicated reasons, might have framed Robicheaux for the murder of the man whose reckless driving caused the death of Robicheaux's wife. Among the characters is a writer whose novel about a Confederate soldier teaching a black boy to read provides the basis for a film currently in production in New Iberia.

The spectral presence of secessionists and rebel armies informs the novel’s brilliant exploration of shame and glory. Every civilization, like every inhabitant of a civilization, carries the weight of shame underneath the banner of glory. David Robicheaux honors his profession and serves his community, but he also fears his own capabilities, especially when seduced by the succubus of alcohol. He was drinking the night of the murder, and blacked out. Too often he has surprised himself with his own acts of violence in the exhibition of an “ends justifies the means” philosophy of vigilante justice.

The Southern United States has a rich history and distinct culture — the source of pride in a Louisianan like Robicheaux's — but it was also the home of slavery, the birthplace of the Ku Klux Klan, and the most iniquitous enforcement of Jim Crow.

Supporters of a populist manipulator are often brave, and willing to make physical and emotional sacrifices for the sake of their families as a matter of daily routine, but will applaud declarations of hatred for those of different ethnic complexion, and enable the slow but steady demolition of civil society.

Burke, using the tour guide of David Robicheaux, navigates political and ethical terrain throughout his newest novel, but never do the characters feel like props for ideological argument, and never does the story seem like an excuse for pontification.

One could read, without thinking about anything in the headlines, about David Robicheaux’s struggle to clear his own name, even if only to his own conscience, as a brilliant innovation on the classic murder mystery: The detective must investigate a case in which he is the prime suspect.

One could also read about Clete Purcel’s own challenge without experiencing a political interruption. He’s taken into his care a child who suffered the abuse of a cruel father, attempting to simultaneously protect the child from his own family and from the foster care system that could place him in a situation of similar pain and misery.

It is impossible, however, to read “Robicheaux” or any of Burke’s books without deeply reflecting on the moral conflicts of our time and any time. Burke has an unbreakable focus on injustice and inequality. In the new novel, the unsolved and largely unlamented murders of eight poor sex workers in Jefferson-Davis County act as a reminder that “law and order” is often a privilege for the wealthy, and an unaffordable commodity for anyone in the bottom quarter of income earners.

No matter his subject, Burke manages to elevate above his peers and ascend to the high ground of art, through the sheer force of his dazzling, and at times heart-stopping, prose. One of current maladies afflicting American life is the debasement of language. Burke’s mastery of articulation and description becomes not only a wonder to behold, but also an act of subtle subversion against cultural mediocrity.

As an example, consider how Burke enters the mind of a killer leaving an urban crime scene: “The neon glow of the club slid off his body like dissolving watercolor. See? he thought. Life wasn’t complicated at all. In a minute he would be gone, subsumed inside the great American night, a tiny point of light inside a galaxy that became a snowy road arching into infinity.”

Those who share a sense of trembling for America, and the state of the world, with Robicheuax, Purcel, and James Lee Burke, might do even better to reflect on the detective’s own hardboiled theology:

How do you handle it when your anger brims over the edge of the pot? You use the shortened version of the Serenity Prayer, which is “Fuck it.” Like Voltaire’s Candide tending his own garden or the British infantry going up the Khyber Pass one bloody foot at a time, you do your job, and you grin and walk through the cannon smoke, and you just keep saying fuck it. You also have faith in your own convictions and never let the naysayers and those who are masters at inculcating self-doubt hold sway in your life. “Fuck it” is not profanity. “Fuck it” is a sonnet.

James Lee Burke, with beauty, strength and grace, continues to do his job, and that is one consistency that should help fellow travelers maintain their faith and direction as they march onward.

Shares