Gale Dunham, a pharmacist in Calistoga, Calif., knows the devastation the opioid epidemic has wrought, and she is glad the anti-overdose drug naloxone is becoming more accessible.

But so far, Dunham said, she has not taken advantage of a California law that allows pharmacists to dispense the medication to patients without a doctor’s prescription. She said she plans to take the training required at some point but has not yet seen much demand for the drug.

“I don’t think people who are heroin addicts or taking a lot of opioids think that they need it,” Dunham said. “Here, nobody comes and asks for it.”

In the three years since the California law took effect, pharmacists have been slow to dispense naloxone, which reverses the effects of an overdose. They cite several reasons, including low public awareness, heavy workloads, fear that they won’t be adequately paid and reluctance to treat drug-addicted people.

In 48 states and Washington, D.C., pharmacists have flexibility in supplying the drug without a prescription to patients, or to their friends or relatives, according to the National Alliance of State Pharmacy Associations. But as in California, pharmacists in many states, including Wisconsin and Kentucky, have divergent opinions about whether to dispense naloxone.

“The fact that we don’t have wider uptake . . . is a public health emergency in and of itself,” said Virginia Herold, executive officer of the California State Board of Pharmacy. She said both pharmacists and the public need to be better educated about the drug.

Pharmacists are uniquely positioned to identify those at risk and help save the lives of patients who overdose on opioids, said Talia Puzantian, a pharmacist and associate professor of clinical sciences at Keck Graduate Institute School of Pharmacy in Claremont, Calif.

“There’s a Starbucks on every corner. What else is on every corner? A pharmacy. So we are very accessible,” Puzantian told a group of pharmacy students recently as she trained them on providing naloxone to customers. “We are interfacing with patients who may be at risk. We can help reduce overdose deaths by expanding access to naloxone.”

Opioid overdoses killed 2,000 people in California and 15,000 nationwide in 2015.

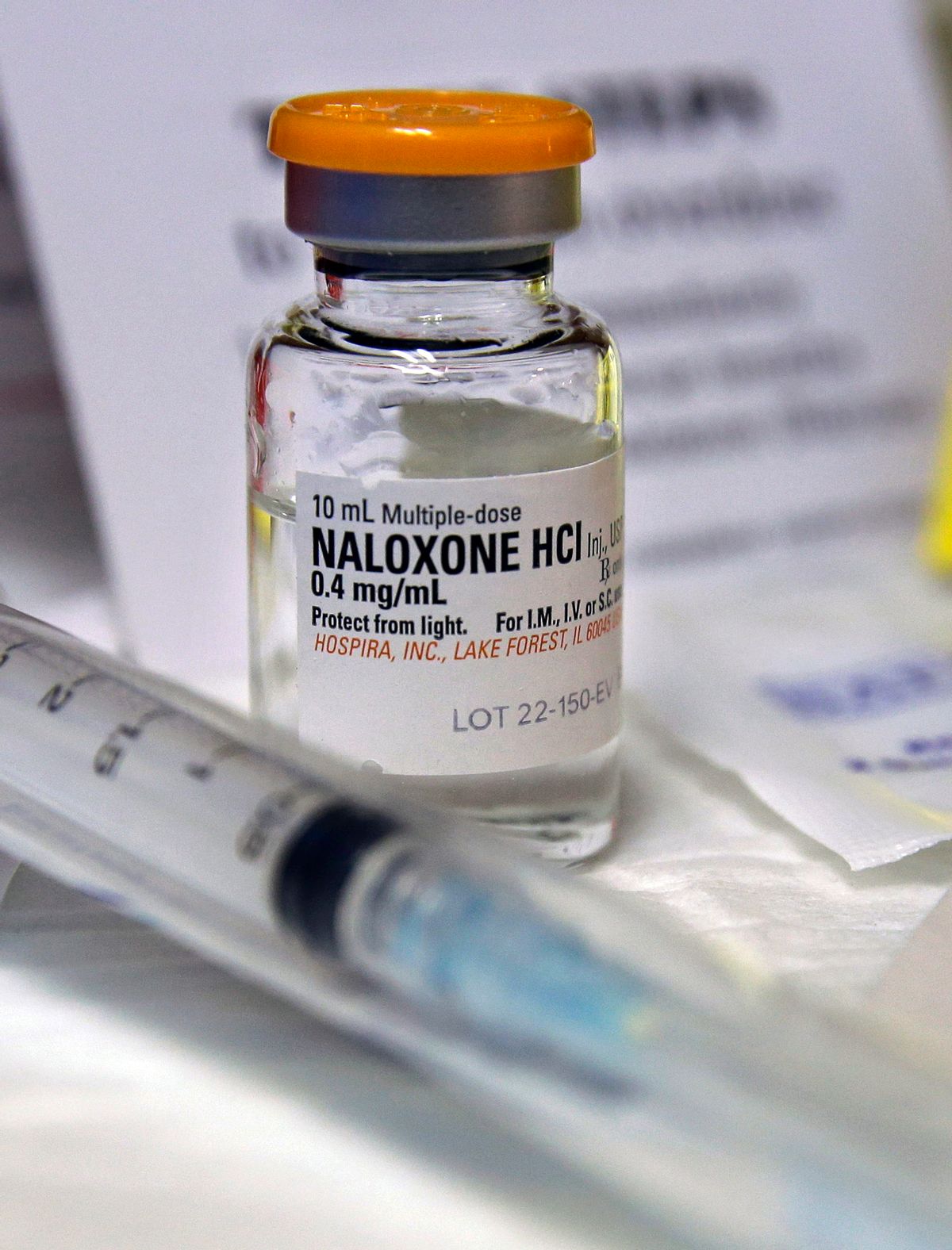

Naloxone can be administered via nasal spray, injection or auto-injector. Prices for it vary widely, but insurers often cover it. The drug binds to opioid receptors, reversing the effect of opioids and helping someone who has overdosed to breathe again.

At least 26,500 overdoses were reversed from 1996 to 2014 because of naloxone administered by laypeople, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Since then, the drug has become much more widely available among first responders, law enforcement officers and community groups. The drug is safe and doesn’t have serious side effects, apart from putting someone into immediate withdrawal, according to the institute.

Information on how many pharmacists are dispensing naloxone is limited, but one study last year showed access to the drug at retail pharmacies increased significantly from 2013 to 2015 from previously small numbers.

Shares