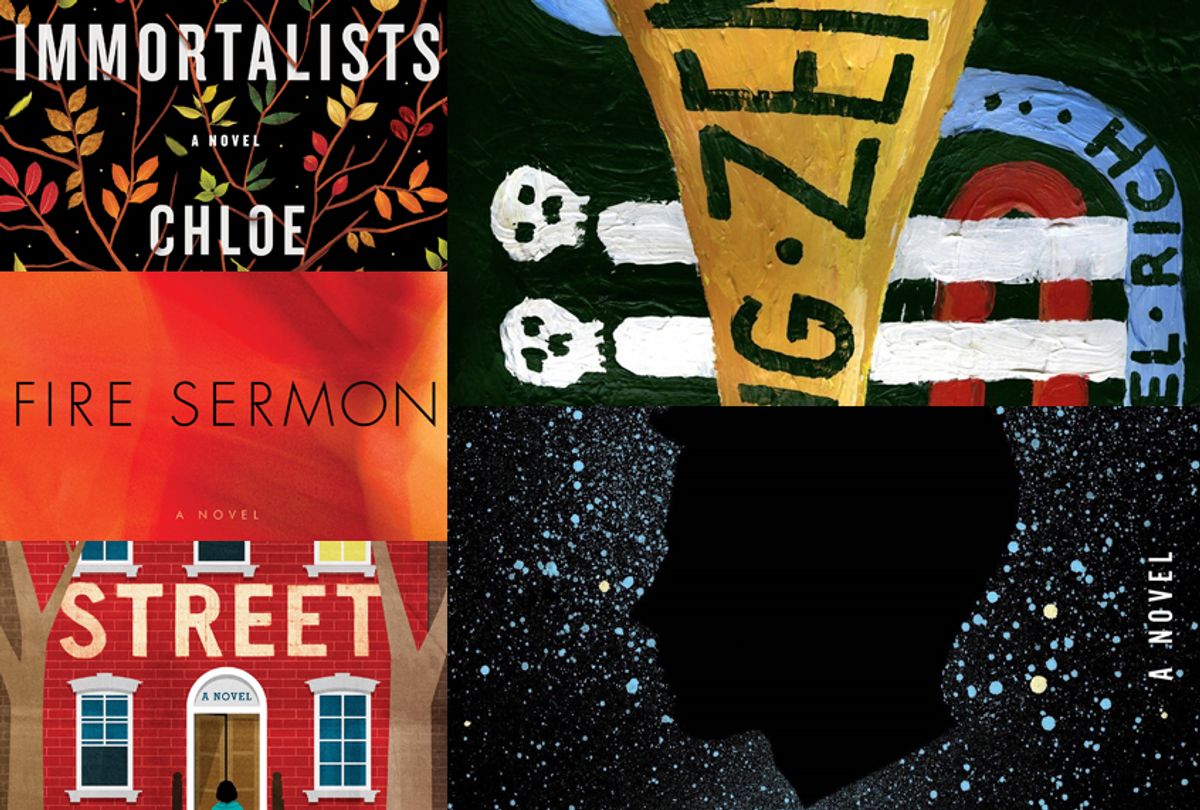

For January, I posed a series of questions — with, as always, a few verbal restrictions — to five authors with new books: Stefan Merrill Block ("Oliver Loving"); Chloe Benjamin ("The Immortalists"); Naima Coster ("Halsey Street"); Jamie Quatro ("Fire Sermon"); and Nathaniel Rich ("King Zeno").

Without summarizing it in any way, what would you say your book is about?

Stefan Merrill Block: Family, speechlessness, storytelling, teenage heartbreak, Texan lore, parental anxiety, adolescent rebellion, gun violence, arty poverty, Brooklyn, border crossings, small town life, pug ownership, astrophysics.

Chloe Benjamin: Fate vs. chance, reality vs. illusion, religious faith vs. magic, the past vs. the future, life vs., well, death (it's a fun read, I swear!). It's also about siblings, and the combination of closeness and distance that can characterize those relationships in adulthood.

Naima Coster: The weight of familial duty, unbearable feelings, cross-racial tension and intimacy, city life, anger, art-making, discontented mothers, lonely daughters, daydreaming fathers, home as a hard place.

Nathaniel Rich: Underground forests. The Axman panic, the highwayman panic, the jazz panic. The control of nature. The horrors of parenthood. The vanities of immortality. The fear of going to pieces. The thrill of going to pieces.

Jamie Quatro: Illicit sex, marital fidelity, loss of virginity, childbirth, parenting, sex toys, marital rape, poetry, 9/11, digital eroticism, dogs and cats, "Harry Potter" as therapy, the intersection of Buddhism and Christianity, the sexually ecstatic as a pathway to God.

Without explaining why and without naming other authors or books, can you discuss the various influences on your book?

Rich: The swamp; “The Whore’s Gone Crazy” and “Make Me a Pallet on the Floor”; the Industrial Canal, Bayou Bienvenue, the Mississippi River; Buddy Bolden, Kid Ory, Louis Armstrong; the struldbergs of Luggnagg.

Coster: Gin, gentrification, Brooklyn brownstones, the A train, the mountains of the Dominican Republic, John Coltrane, jazz, the ocean, ships and journeys.

Quatro: My deceased grandmother’s love letters to a man who wasn’t her husband, light on the Hudson River, Bach’s English and French Suites, mysticism.

Block: Texas, New York City, the gun violence epidemic, Bob Dylan and Leonard Cohen, the photographs of James H. Evans, Atom Egoyan’s film "The Sweet Hereafter," "The Leftovers" TV series, my friends, Trumpish jingoism, neuroscience, teenage loneliness, homeschooling, the exigencies of New York City life, a Hill Country ranch called Paisano.

Benjamin: Fear. My mom's breast cancer. Female magicians. Sex and sex work in San Francisco. Ballet. The agony of uncertainty, and the freedom of uncertainty. Koko, the signing gorilla. The Iraq war. Tiny Kline. My stepmother, who brought Judaism into my dad's (ancestrally Jewish but presently atheist) home. Regret. My brothers. Ferocious, complicated love, and its consequences. Joan Didion said that we tell ourselves stories in order to live, but is it a story if you believe it? Red hair. Longing. Turritopsis dohrnii, the immortal jellyfish. Surprises.

Without using complete sentences, can you describe what was going on in your life as you wrote this book?

Quatro: Cheating on my contracted novel to write this one.

Block: Spent six months in Texas, moved back to Brooklyn, paced Prospect Park with head tilted slightly to one side, fell in love, got married, learned to cook, spent a few months in Italy, turned 30, completed first draft, turned 31, threw away first draft, turned 32, started book over, turned 33, -4, and -5.

Benjamin: Working at a health nonprofit, then a shelter for victims of domestic violence. Early mornings at my desk with blue light coming through. Getting married! Publishing my first book. A snowy month in a garage apartment in Vermont where I wrote a prologue I never used. A family crisis. Political apocalypse. Friends gathering, then dispersing. A gray fluff ball in the shape of a kitten, my first pet.

Rich: Marriage, childbirth, and fatherhood. Secondary events: a humbling at the paws of an opossum; the observation of cultural, political, and environmental collapse on a scale unimaginable even five years ago; the semi-successful operation of a backyard compost.

Coster: Getting married and learning to be close, the death of my uncle, the sudden death of a dear friend, beginning therapy and breaking old bad habits, graduate school, awkward boozy parties, leaving New York.

What are some words you despise that have been used to describe your writing by readers and/or reviewers?

Coster: Quiet. I don’t really know how it applies! There’s a lot of drama in my novel. And yelling. And crying. And kicking over trash cans. Maybe that’s just the language we most readily use to describe a book about the inner lives of women. Or maybe I’ve misunderstood, and it means ‘this story will sneak up on you,’ in which case, never mind, I like it.

Block: Years ago, my best friend Anne became incensed when she saw the word “ambitious” in the review of some famous male writer; Anne had noticed that “ambitious” was a word almost exclusively applied to men. “But who would even want to be called ambitious? What they really mean by ambitious is posturing,” I said. “Don’t be crazy,” Anne countered, “of course they mean it as a compliment.” I told Anne that I wasn’t sure about that, and I’m still not sure today. But over the years, I’ve seen that Anne had a good point — even now, I think that “ambitious” is unequally used to describe men’s work. So, given the gender politics and contradictory implications of that particular word, it always makes me uncomfortable. And yet, there it was in one of my first trade reviews for "Oliver Loving": “Ambitious.”

Quatro: “Confessional,” which implies the fiction is about the author; “confess” implies there must be shame behind the writing. Never assume either, regarding a work of fiction.

Benjamin: Some people describe the book or the four main characters as sad—Kirkus labeled them “an unhappy bunch"—which frustrates me. Yes, they cope with depression and even tragedy, but don’t we all? There are still funny moments and love stories and magic shows! I’ve also seen the sex in of the book described as crass, which seems to be connected to the fact that it's had by a gay couple instead of a straight one. I’ve even seen reviews that include warnings about gay sex—demoralizing, to say the least.

Rich: “Zzzz…” the sound of my wife reading the first draft of my first novel, upon falling asleep on the first page.

If you could choose a career besides writing (irrespective of schooling requirements and/or talent) what would it be?

Benjamin: If I were a few clicks more analytical, a lawyer. If I had less stage fright, a dancer or a stage actor. As is, a test knitter.

Rich: A starting pitcher in the NL with a plus breaking ball and pinpoint command.

Block: Before I published my first book, I worked for a while as a documentary and wedding/bar mitzvah videographer, and a part of me still mourns the lost filmmaker I’ll never be. Working on a documentary is nearly the opposite artistic process to writing: as a writer you are always trying to fill out a world to fit your story, but as a documentarian your work is to carve a story out of the world. Sometimes, when I’m feeling particularly blocked at my computer, I miss the days when I could just point my camera at something interesting and wait to see what happens.

Quatro: Broadway musical theater—preferably a Schuyler sister in "Hamilton," but I wouldn’t be picky.

Coster: Singer-songwriter, for sure.

What craft elements do you think are your strong suit, and what would you like to be better at?

Coster: Writing the interior of characters comes very naturally to me. I’d like to try my hand at a quest story full of physical obstacles, not only the social or psychological kind.

Quatro: I’m pretty good at reading my drafts aloud to figure out where the cadence or beat needs to change. I’d like to stop avoiding the torture of writing by getting on Twitter or Instagram or Realtor.com/international to see how much houses cost in countries where Trump isn’t president.

Benjamin: I'm proud of my ear for dialogue, my psychological insight and my prose, which is (at its best) musical and revealing. I can't for the life of me figure out how to write physical descriptions well—it's so easy to fall back on stock descriptors. And good plotting is an ongoing challenge.

Rich: I am a practiced self-savager. I would like to be better at everything.

Block: I’d hate to think what a therapist (or my wife) might read into this, but I think that I write much more naturally about characters in solitude than characters interacting with others. My natural inclination—and one that I’ve learned to push against—is to give primacy to a character’s interior world. Over the three books (and now three and a half) that I’ve written, I’ve had to teach myself that not every feeling needs to be described and that often the most impactful writing more elegantly evokes those unnamed feelings through the way characters speak and behave.

How do you contend with the hubris of thinking anyone has or should have any interest in what you have to say about anything?

Block: I don’t write because I think I have anything particularly interesting to say. I write because I love writing more than any other work I’ve done. I do think about entertaining the reader to the extent that I try always to write a book that I myself would want to read, but I don’t think it’s up for me to decide if what I’ve written is interesting to others. That is entirely up to others.

Quatro: I never think anyone should read anything I’ve written. I draft and revise until I’m sick of every word. That’s how I know something might be close to finished.

Benjamin: I do worry about this—or, put differently, the hubris of permitting myself to keep writing instead of trying to be a social worker or a doctor or something of more obvious use to other people. I contend with it by remembering that books have the power to profoundly impact people's lives, which I know because they have done this to mine.

Coster: I worry far more about the voice in my head that tells me to keep quiet. The way I see it, there’s a place for my voice, my interests and imagination, as much as anyone else’s.

Rich: Who’s asking?

Shares