There is a big question underlying all of American history, which has been thrown into stark relief by the current tragic or nightmarish state of our nation. It cannot be reduced to politics or ideology, in the usual sense. It cuts across divisions between Republicans and Democrats, right and left, those who love Donald Trump and those who despise him. It partly (but only partly) accounts for differences between pro-Trumpers and NeverTrumpers in the Republican Party, between the stillborn, quasi-Nazi “economic nationalist” movement of Steve Bannon and the so-called conservative mainstream.

This question also partly explains the contentious quarrel between progressives and moderates within the Democratic Party coalition, which is often said to involve relatively minor disagreements over policy. (I’m not sure that’s true, but that’s a topic for another time.) There is no doubt that the question shapes responses to the Russia scandal surrounding the Trump administration, which is variously understood as an existential threat to American democracy, a farcical display of incompetence or low-level criminality, and a liberal (and/or Deep State) plot to destroy Our Führer. I’m sorry; that was hurtful. Of course I mean our duly elected president.

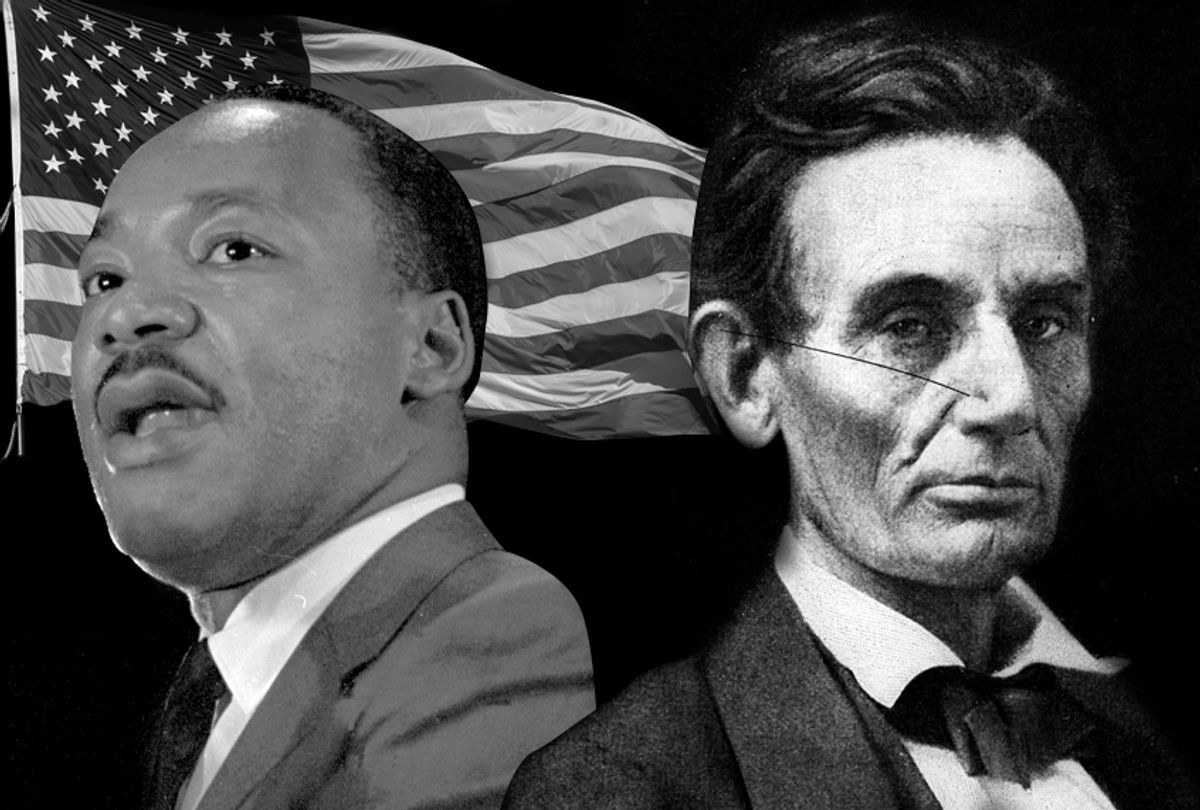

The question can be simply stated, which doesn’t mean everyone understands it in the same way, still less that anyone knows the answer: Can America be saved? Can the vision of American possibility so memorably articulated on the Capitol Mall by Martin Luther King Jr. — whose birth, life and death we honor this weekend — still be redeemed or renewed as something we collectively aspire to, and strive toward?

Is the dream that King captured on that day in 1963, grasping the challenge that Abraham Lincoln flung forward to posterity at Gettysburg 100 years earlier, and the one Thomas Jefferson (shameless hypocrite that he was) set down on paper 87 years before that, still alive around us and in us? Or have we downgraded ourselves into a shithole nation, poisoned by greed, bigotry, ignorance and a profoundly unwarranted belief in our own greatness?

This fundamental question about the character of America — America now, under the extreme conditions of 2018; America in history; America in the future — also shaped the range of responses to President Trump’s repugnant “shithole” comments on Thursday. I’m not sure anyone can claim to be surprised that Trump would think such things about nonwhite nations in the developing world, or would say them out loud during what he perhaps understood as a private meeting. Furthermore, the Trumpian cult’s defense -- that the president was just ventriloquizing the common man, and that people often talk this way at the “kitchen table” -- is essentially correct. Many Americans would say those things, because many Americans have been conditioned to racism and ignorance and a lack of human empathy.

Those of us who do not lack empathy were understandably heartened to see so many mainstream political figures, including a handful of Republicans, express outrage and disgust at Trump’s comments. But if the president crossed some kind of line on Thursday, where was it exactly? What possible standards of morality or decency or dignity still existed that he had not violated countless times in the past? The spectacle of Trump pretending to celebrate King’s birthday the following day was admittedly nauseating. It would have been marginally more decent, and a great deal more honest, for him to have refused to acknowledge the holiday at all.

I think we can conclude, in fact, that Shithole-gate changed nothing. Those conservatives who spoke out most forcefully against Trump, including commentator Bill Kristol, Sen. Jeff Flake of Arizona and Gov. Charlie Baker of Massachusetts, are known NeverTrumpers who had long ago concluded that for reasons of principle or self-interest or both they would not stand with the despicable oaf in the White House. (Look for several blue-state Republican governors, including Baker, Larry Hogan of Maryland and Bruce Rauner of Illinois, to consider switching parties or running for re-election as independents.)

For those people, as for establishment Democrats like Sen. Dianne Feinstein — who seemed to suggest for the first time that Trump was not fit to hold his office — and for much of the Beltway press corps, the central question goes well beyond what sort of person they believed the president was until now. I don’t think they were confused about that, or that it’s entirely fair to accuse them of hypocrisy. Perhaps they pined for the infamous “presidential pivot” for much too long, trusting that the office would prove larger than the man. That was naïve, delusional and pathetic, but it was not exactly hypocritical.

Failing that, leading figures in the Democratic Party and the media (along with some conservatives) apparently concluded that treating Trump with at least the minimal respect and deference traditionally accorded to the presidency might help to maintain or restore “democratic norms” in this time of crisis. If it wouldn’t magically make Trump less racist, it might persuade him not to say random racist stuff in the Oval Office when other people were listening. They were playing what could be called a pragmatic long game: “Normalizing” this president, however distasteful he may be, was a way to ensure that someday we would have an orderly transition to another (presumably more normal) president, rather than tumbling into the yawning chaos of fascism or constitutional meltdown that seems to lurk just below the Trump White House.

If it seems ludicrous to suggest that the central problem in Shithole-gate is Trump’s use of foul and abusive language, or the violation of presidential decorum, that’s because nobody actually thinks that. For Jeff Flake and Dianne Feinstein and the editorial board of the New York Times, those things represent Trump’s contemptuous disregard for the ideals on which our nation is supposedly based. They see themselves as the guardians of those ideals, whatever disagreements they may have on policy or ideology. They are willing to put country before party (at least as they understand those things) in defense of the aspirational vision of America handed down from Thomas Jefferson to Abraham Lincoln to King. Trump is endangering America’s future; they seek to protect it.

I’m honestly not sure what to say about that narrative of American exceptionalism, except that it is simplistic and starry-eyed and we will never be rid of it. It has more to do with theology than history; it rests on a whole bunch of unspoken and unproven assumptions; it elides or ignores any number of painful contradictions. I understand the leftist impulse to reject it as a shameful lie, but we cannot mock it into nonexistence or make it stop mattering. If the United States is to endure, we probably can’t do without it. This may be a moment for humility more than cynicism, although I suspect we will need both to survive the Trump presidency and its long-tail aftermath.

This brings us back to the unanswerable central question, which is only partly about how you think things were going in America before the unexpected cataclysm of Nov. 8, 2016 — and whether you think that was an unexpected cataclysm at all or the product of a long historical process. Those of us who insisted that there was a fundamental kinship between Donald Trump’s and Bernie Sanders’ presidential campaigns (a point I argued very early on) were shamed into silence by the Sanders tribe or seized upon by Hillary Clinton supporters as evidence that the Bernie Bros (and the progressive left more generally) were racist, sexist, fascist scum, only with beards and inadequate footwear.

But the real point of contact lay in the fact that both Trump and Sanders perceived a profound moment of crisis in America’s sense of self, which was at once political, cultural and spiritual. Since Sanders was not a fascist (and only notionally a socialist) he did not vow to make America great again or tell his followers that he was their voice and only he could fix it. But that’s how too many of them understood him, and it’s why too many people are now pushing him toward a possible 2020 campaign that is partway between a bad idea and an impending disaster.

Hillary Clinton’s problem was that she did not perceive any crisis at all: America was on an upward trajectory of feminism and entrepreneurship and practical solutions and dubious overseas interventions we didn’t have to think about, and then the deplorables of suburban Michigan dragged us into the shithole. It's important to acknowledge two things here: Clinton got a lot more votes than Trump, so her perspective was not objectively false; and in hindsight she saw her campaign's conceptual failings pretty clearly. She was widely slagged over her memoir, “What Happened,” but I thought it was remarkably frank. In retrospect, Clinton understood that she had gravely misjudged the level of popular discontent, and refrained from blaming her defeat on the vicious, virulent sexism of her coverage in mainstream media (which I suspect was more damaging than whatever the Russians did).

If you believe that the Republican Party will wake up to its constitutional mission and chuck Trump to the curb, or that the blue wave of 2018 or Robert Mueller’s indictments will save us, or that the steely visage of President Kirsten Gillibrand will make all of this seem like it doesn’t matter or didn’t even happen, that is one form of American mythology. If you believe it will take many years of grassroots activism and granular reform and flat-out class conflict to renew the promise of American democracy, that is another. If you believe that none of those things is likely to happen but we will laugh and cry and muddle through somehow as human beings, I’ll meet you at the bar.

If we are to get to the other side of the Trump presidency as one nation and one people — and that’s a big “if” — we will need all those perspectives and more. We will need Keith Ellison and Jeff Flake to stand arm-in-arm (metaphorically speaking), despite their radically different understandings of American history and how we got here. We may also need the kind of larger-than-life historical figure I mentioned earlier: a Jefferson or a Lincoln or a King, born from conflict and turmoil, who for all their personal and political contradictions grasped at a dream and galvanized it and told us to believe in it before it was gone. Whichever version of America you believe in, can it produce such people now?

Shares