Ladies, it’s one thing if we can get a few dozen of us together to corroborate about an alleged serial rapist. Even then, though, are we sure we want to ruin a man’s legacy like that? But when we start naming names when the guy was just messing around, or when we didn’t stop him when he pushed a head to his crotch, well, that’s quite enough. Seems like the real problem here is . . . us.

The past several months have brought a deluge of revelations both large and small about sexual harassment and abuse, both in and out of the workplace. They’ve marked a profound cultural shift in the way we talk about sex and power. Men have lost jobs, lost elections. And when actions start to have consequences, it’s time to trot out the inevitable terrible opinions.

The year kicked off with a much shared New York Times op-ed by Daphne Merkin, who declared that “privately, I suspect, many of us, including many longstanding feminists, will be rolling our eyes, having had it with the reflexive and unnuanced sense of outrage that has accompanied this cause from its inception.” Merkin, it seems, is already weary of “the sort of social intimidation that is the underside of a culture of political correctness.” Nor is she alone.

The issue took on new urgency in mid-January, when rumors circulated that reliable bad-take factory Katie Roiphe was preparing a feature for Harper’s that would name the woman behind the famed “sh**y men” document. The Google document, which began in October, names a variety of male media figures and a spectrum of behaviors ranging from the “inappropriate” and unprofessional to full-fledged assault. A few of the men on the list have since been investigated and vacated their positions.

After word of the Harper’s piece got out, the creator of the list, Moira Donegan, swiftly revealed herself in a bracing and nuanced piece for The Cut. In it, she discussed the reasons for the list and for the variety of behaviors on it. “This is another toll that sexual harassment can take on women,” she wrote. “It can make you spend hours dissecting the psychology of the kind of men who do not think about your interiority much at all. . . . Suddenly, men have to think about women, our inner lives and experiences of their own behavior, quite a bit. That may be one step in the right direction.”

Yet others see that breadth as dangerous. Writing in New York magazine, Andrew Sullivan congratulated himself for predicting this new “moral panic” and railed against “the excesses of #MeToo.” After all, he said as he equated the list to a form of McCarthyism, “This chorus of minor offenses is on the same list as brutal rapes, physical assaults, brazen threats, unspeakable cruelty, violence, and misogyny.” And Sullivan, shocked that Donegan “expresses no regret” for creating the document and alarmed that actions he deems “minor” share a page with felonies, expressed his admiration for those women who “don’t see themselves as helpless, powerless, forever-victims of men.”

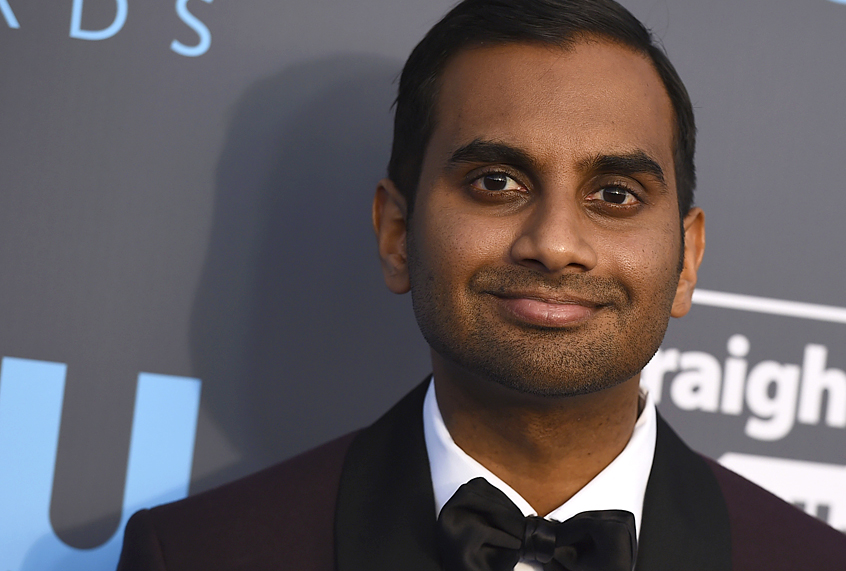

But wait, isn’t power the name of the game here? Over the weekend, when a woman known only as “Grace” revealed a complicated, “upsetting” sexual encounter with “Master of None” creator and star Aziz Ansari in Babe, she opened up a semantic can of worms by deploying the word “assault” to describe it.

Faster than you could say “word salad,” professional pearl-clutcher Caitlin Flanagan was on the case with an Atlantic essay that warned women are “angry and temporarily powerful, and last night they destroyed a man who didn’t deserve it.” Now, Flanagan said, “Apparently there is a whole country full of young women who don’t know how to call a cab, and who have spent a lot of time picking out pretty outfits for dates they hoped would be nights to remember.”

But writing in The New York Times, Bari Weiss said that the Ansari story “transforms what ought to be a movement for women’s empowerment into an emblem for female helplessness.” So are we helpless or power-mad here? Snowflakes or bullies? Whatever you may think of Grace’s narrative, or her use of the unquestionably loaded word “assault,” it’s clear that the eagerness to demand that women limit what we share has become increasingly intense — as if self-policing isn’t exactly what we’ve been doing all our lives.

We carry around our stories as if we may only ever get one to spend. That teacher who made suggestive comments about our bodies when we were twelve — what had we expected, when we’d stubbornly refused to wear a bra yet? The genial supervisor who lived up to the quiet warnings about getting a little too handsy at parties — hey, hadn’t we been grateful to work in such a creative, fun environment? The charming, sexy date who pinned us down until we decided, in a quick moment of mental math, that it’d be easier and safer to just stop saying no — we hadn’t said “no” when he kissed us, right?

We live in fear of squandering our narratives on such seemingly trivial things, because we know the day may come when we need to tell a bigger story, and we want our histories to be spotless. We know the cost of scrutiny, the questions we’ll be asked. Why did you let him sign your yearbook? Why did you keep working with him? Why did you text him the next day? Why did you tell him it was all OK when you felt that he’d hurt you? Why did you pick out a pretty outfit? Why did you behave exactly as if you have been trained to be pliant and quiet and to question only yourself?

Plenty of women — women who have had experiences ranging from catcalls to coercion to violent abuse — can differentiate catcalls and coercion and violent abuse in their minds. We know that a grope isn’t a rape. We’re just sick and tired of acting like we’re supposed to be grateful when a grope isn’t a rape. We’re sick of starting sentences with “At least he didn’t . . .” We’re sick of smiling self-protectively because we just don’t know what the repercussions might be if we wound this man’s pride. We’re sick of being accused of being buzzkills, even though plenty of capable grown-up people, men and women alike, know the distinction between friendliness and hostility, between flirtation and aggression. We’re sick of wondering exactly how bad it has to be before we give ourselves permission to talk about it.

A great many of the things that wear us down the most go on in private, in the most intimate spaces of our workplaces and schools and homes. Calling out not just the very worst of it, but also the things that need a whole lot of improvement, is fairly new territory. Yet it’s vitally important. As “Girls & Sex” author Peggy Orenstein says, “Consent is such a low bar.” We deserve so much more. More than, “Welp, I didn’t mace the guy so I guess that’s on me.” So you keep those hot takes coming, clickbait contrarians, about how we’re too fragile or too demanding or how we’ve gone too far now. Keep accusing us of everything we’ve been afraid of being accused of. It’s not so scary anymore. And just know that now, when you single out a woman who speaks up as being hysterical, a whole lot of us are going to shout back, “Yeah. Me too.”