A few years into Obama's first term in office, I taught my final section of an interdisciplinary undergraduate seminar I had designed on popular music and American literature. Roughly 75 percent of the time I taught that class at this small liberal arts college, my student roster was 100 percent white. One of my semester-end reading assignments in that course was bell hooks' essay "Madonna: Soul Sister or Plantation Mistress?" And during one of those final discussion periods of that last semester I taught, one that if I recall correctly was an all-white class, one of my students exploded. "Racism is over," she fumed. "My friends and I, we don't see race. We all talk about everything and nobody cares what color anyone is. Professors like you are the reason why racism still exists, because you keep bringing it up."

At the time, the outburst startled and bewildered me. But I came to understand that it was possible that nothing in that student's life up to that moment had prepared her to have a conversation about bell hooks' analysis of Madonna. And she's far from alone in reacting with hostility instead of engagement when confronted with frank conversation about racism in America. Today, the pussyfooting that politicians and publications have done around calling even blatantly racist statements and actions by President Donald Trump by their rightful name underscores how far white America still has to go when it comes to tackling the subject of race with clear eyes and minds, and open hearts.

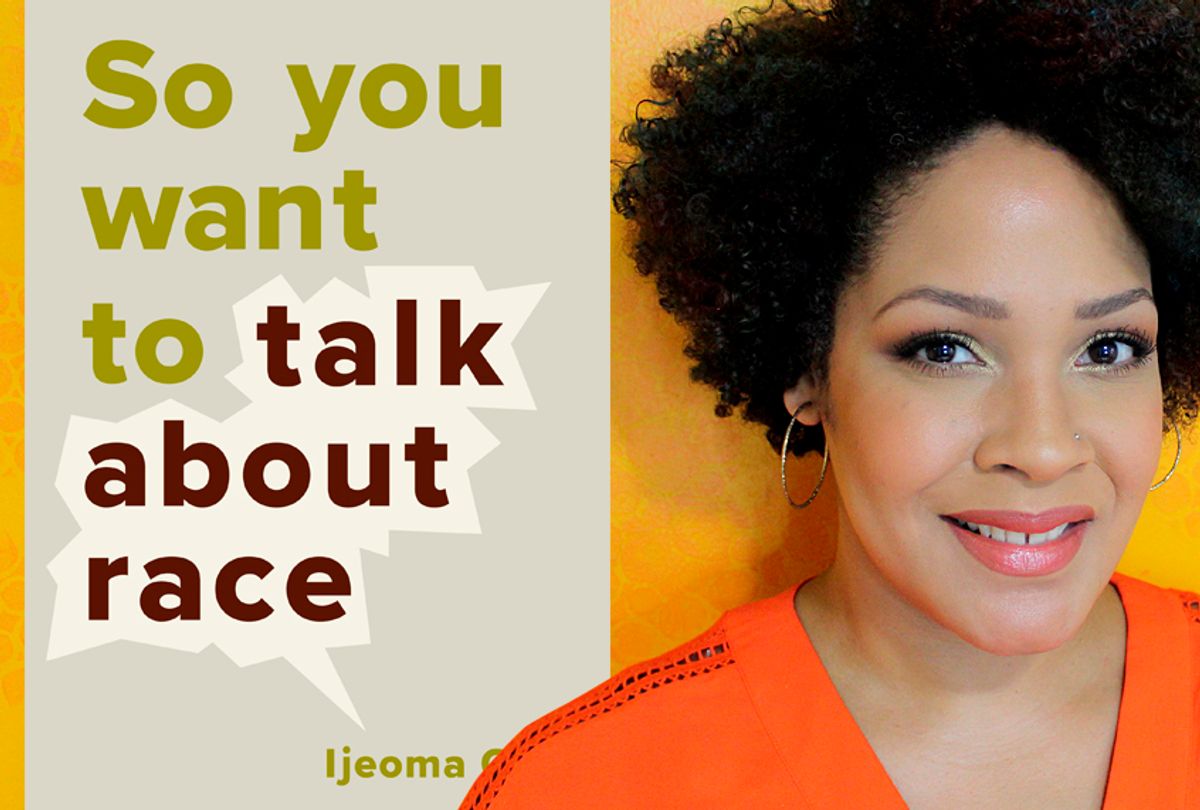

As author Ijeoma Oluo writes in her new book "So You Want to Talk About Race" (Seal Press, published Tuesday), "[t]o many white people, it appears, there is absolutely nothing worse than being called a racist, or someone insinuating that you might be racist, or someone saying that something you did was racist, or somebody calling somebody you identify with racist." In an act of nauseating irony, "racist" has been re-interpreted by white people as a kind of nuclear option term of abuse rather than a useful descriptor, and as a result we will often go to great lengths to avoid using it.

Perhaps, as the thinking of a pissed-off sophomore might go, to even be discussing whether Madonna's ability to profit off black culture and imagery is rooted in racism feels dangerously close to being called a racist yourself just for liking Madonna, which is to say accepting that you are irredeemably evil, since that's what racists are, right? So your professor just basically called you evil in front of everyone for liking an old pop song? Cue a reflexive emotional shut-down.

That's not just a naïve student thing — Oluo cites as evidence the anecdote from George W. Bush's memoir in which he claims the moment Kanye West called him out for not caring about black people as the low point of his presidency. And it's not just a Republican thing, either. Many liberal white adults who see ourselves as the opposite of Trump (or Dubya) on racial issues bristle just as easily at the idea that we might be racist, or say and do racist stuff, as conservatives who want to believe the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was the final word on equality and anything else is just "playing the race card." When people of color call this behavior out — because it still falls disproportionately on those who are disadvantaged by it to point racism out, both situational and institutional, no matter how many white professors teach bell hooks essays — they are often asked to "educate" the person on the issue in question, preferably in the most gentle and encouraging way possible. Dialogue is necessary, and yet this teaching is often unpaid and thankless work. Oluo's book — one that would be a highly productive book-in-common for high school seniors in America — can help.

Oluo, editor-at-large at The Establishment, has written a generous and empathetic yet usefully blunt guide to confronting and interrogating the many ways race informs prejudices that are reinforced by systems of power in America. Accessible and approachable in tone, "So You Want to Talk About Race" is aimed squarely at those who actually do. In other words, this isn't a book to pass quietly to your slur-spewing uncle in hopes of getting him to stop sharing odious Obama memes on Facebook, nor is it an instruction manual on how to "not see race."

The book is, however, for the progressive who thinks the Democrats need to "stop pushing identity politics" and talk only about class; it's for folks who don't understand why saying All Lives Matter isn't helpful and why certain Halloween costumes are "not OK anymore"; it's for the person who has absorbed both derogatory myths about Latinx people and "model minority" myths about Asian-Americans and is open to exploring in a frank yet constructive manner why they are both harmful; perhaps it is for the young woman in my class who seemed to sincerely believe that racism was a haunted thing that manifested itself only when named in the classroom by malevolent professors intent on harshing the post-racial buzz; and really, it's for anyone who wants to be smarter and more empathetic about matters of race and engage in more productive anti-racist action.

Oluo weaves stories from her own life through her research to put faces and voices to such fraught topics as "What is the school-to-prison pipeline?" and "Is police brutality really about race?" As a result, the lessons, while still intellectually rigorous, feel more intimate than those gleaned from academic texts and perhaps more likely to make a meaningful impression on the lay reader.

A book with a long publishing lead time can't necessarily keep up with the myriad specific and new examples of racism that crop up in our news feeds every day, but some lessons can be applied broadly. Last Thursday, The Washington Post reported that after a meeting with members of Congress from both parties about immigration in the Oval Office, the president denigrated immigrants from Haiti, El Salvador and Africa as hailing from "s**thole countries." The president's racist profanity made immediate headlines and elicited no small amount of backlash. Some of the well-meaning backlash came in the form of white people using the word "s**thole" ironically, to highlight the achievements of people who hail from the countries the president insulted. Many people of color weren't amused, though, and perhaps this was confusing to those who believed they were making an anti-racist point with their language. In her chapter "Why can't I say the 'N' word?" Oluo carefully breaks down why good intentions don't make it OK for white people to use words that have been used to harm people of color — and yes, I think we can apply that to ironically turning a racist president's ignorant words back on him — because of the power words have had "to separate, dehumanize, and oppress" people of color throughout the history of the United States. When a white person uses racist language, even as an ironic weapon, "that use will continue to be abusive. Because they are still benefiting from how these words have been used while people of color still suffer."

It can be surprising to hear that you are contributing to oppression when you think you are publicly fighting against it. Throughout her book, Oluo emphasizes how difficult these conversations about race will be, but also how necessary and urgent they are for people to have in good faith. And difficult they are for her, too, a professional writer with a degree in political science who is known for writing about race and identity, for now. "As a black woman, I'd love to not have to talk about race ever again," she writes. "I do not enjoy it. It is not fun. I dream of writing mystery novels one day. But I have to talk about race, because it is made an issue in the ways in which race is addressed or, more accurately, not addressed." She invites the reader to "get a little uncomfortable," because racial inequality and injustice are real — we can't "wish it away."

I think about that student a lot now — does she remember that uncomfortable day in class as indelibly as I do? Did she ever go back and read that essay by Dr. hooks and look at Madonna's old videos and figure out where her discomfort really came from? Maybe not. How often do we revisit the lessons that we felt shamed by, even if we couldn't name that as the root of our anger at the time, and especially when our teachers then weren't prepared to help us make productive work of that feeling? I could have used a book like this to give to her, even if she didn't want to read it then. She might now. The years since that class meeting have brought racial prejudice and its reinforcement through power to the forefront of our national conversation time and again. Until people of color have the luxury of not talking about it, white people shouldn't get to take a pass, either.

Shares