When President Donald Trump claimed that he didn’t want America to accept immigrants from “shithole countries” such as those in the Caribbean and Africa — Trump has more or less denied saying this, but anyone who believes him needs their head examined — he was being a racist, a xenophobe and an all-around ignoramus.

What he was not being, however, was un-American.

If progressives and decent people everywhere are going to combat the scourge of Trumpism, the first step is recognizing that it didn’t begin with Trump. For as long as America has been a sovereign nation, racist policymakers have attempted to impose various limitations on the ethnicities of the immigrants who can become citizens. The most glaring modern example of this was the Johnson-Reed Act of 1924, which developed quotas that increased the number of visas available to people from Western European countries, limited those available to residents of Southern and Eastern European countries and outright banned immigrants from Asian countries (many of whom had already been barred under previous immigration laws).

If the Johnson-Reed Act wasn’t the first American immigration law to be blatantly racist, it arrived at a moment when Americans regarded as “nonwhite” — a term that at that time would have encompassed not only people of African, Asian and Latino descent but almost anyone whose ancestors came from outside northwestern Europe — began to gain more cultural and political power. The stirrings of what became the modern Civil Rights movement for African Americans were starting to be felt, while cultural phenomena like the rise of jazz music were terrifying white nationalists everywhere.

Terrifying news stories implied that every Italian was a mobster and every Jew was a predatory capitalist (or a mobster). When New York governor Al Smith made his first run for president in 1924, the fact that he was a Roman Catholic of Irish and Italian descent divided the Democratic Party and the nation. Ku Klux Klan membership boomed; delegates at the Democratic convention could not agree on a nominee until the 103rd ballot. (It wasn’t Smith, although he won the nomination the next time around.)

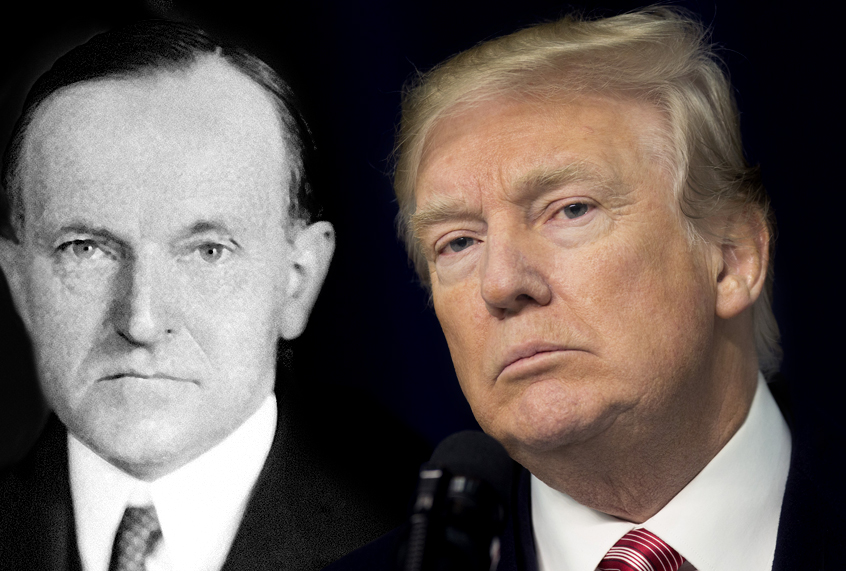

It was against this backdrop that Presidents Warren G. Harding and Calvin Coolidge clamped down on immigration from the countries that they and their supporters would have regarded as the “shitholes” of their time. Similarly, as Ta-Nehisi Coates pointed out in October, Trump was elected president in large part as a reaction to events that shook white supremacy to its core — the election of an African-American president who passed landmark legislation in the areas of health care reform and economic regulation, the perceived rise of “political correctness” and so on. So it makes sense that one of Trump’s core issues all along has been immigration, which has resurfaced repeatedly whenever white nativists have attempted to reinforce their control over American society.

Trump may not have consciously realized that he was plucking the strings of history — it seems unlikely that he’s ever heard of the Johnson-Reed Act — but there can be little doubt that he intuited what he was doing. This is why Trump’s campaign announcement speech in 2015 didn’t just promise more restrictive immigration policies, but played off the racist stereotype that undocumented Mexican immigrants were rapists or killers. It explains the evident cruelty behind Trump’s cancellation of provisional residency permits for 200,000 Salvadoran migrants who sought refuge in the United States after a devastating earthquake, his thrice-attempted ban on Muslim immigrants, or his treatment of undocumented immigrant children who have always known America as their home as a political bargaining chip.

These are the actions of a man for whom the phrase “shithole countries” isn’t just a shocking expletive, but the distilled essence of an entire ideology. While it is difficult to imagine other anti-immigrant presidents stooping to the use of such rhetorical vulgarities — not even the gaffe-prone Harding or the intolerant Coolidge would have said that in the hearing of opposition senators — they still harbored the same ideas.

In a sick, sad way, that’s the perfect way to sum up Trump’s entire political legacy. He doesn’t really represent anything new on the American scene, but he takes bigotry and hatred that was once expressed in quieter and more polite terms and makes it uglier than ever.