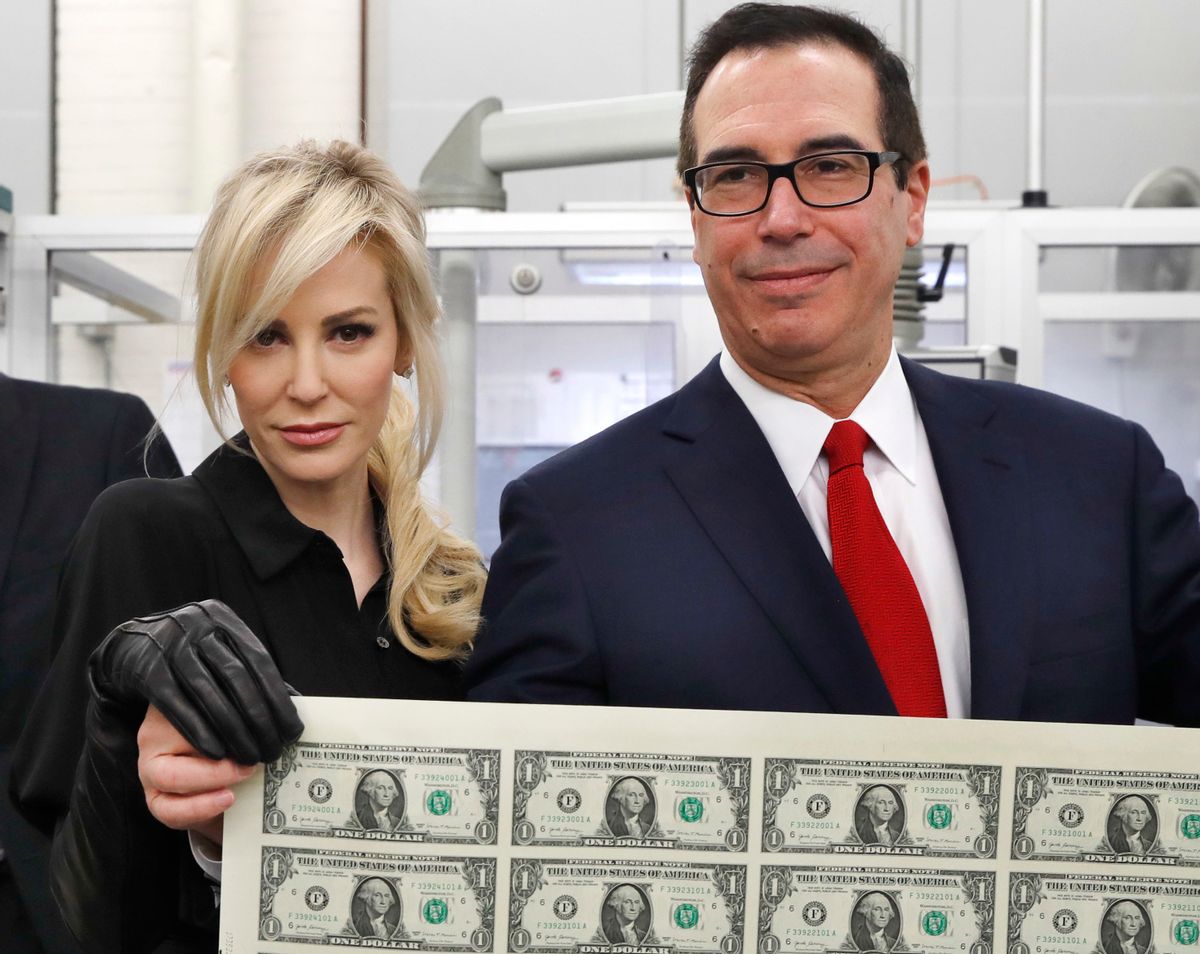

Breaking with long-standing tradition, U.S. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin endorsed the weakening of the dollar as “good” for the United States.

Speaking during a panel at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, on Jan. 24, Mnuchin said: “Obviously, a weaker dollar is good for us as it relates to trade and opportunities.”

The reaction was swift. The greenback dropped like a stone as news of his comments spread, hitting a three-year low in currency markets.

Never before in living memory has one of America’s top economic officials spoken in favor of a weaker dollar. The president himself dove into the mix by reassuring nervous investors after he arrived in Davos that he does, in fact, favor a stronger dollar.

Indeed, that’s been the usual mantra out of Washington for decades. Mnuchin’s immediate predecessor, Jacob Lew, for example, put it this way: “A strong dollar has always been a good thing for the United States.”

So it came as a shock to many — including me — when Mnuchin declared that a depreciation of the greenback is “obviously” welcome. As a specialist in currencies, I think it’s worth briefly highlighting what exactly was so alarming about what the treasury secretary said.

What a weaker dollar does

Mnuchin may have begun to realize he went too far soon after he made his remarks on Jan. 24 – or noticed the dollar’s sudden plunge — because the next day he tried to walk them back, declaring that the Trump administration is not really concerned with “where the dollar is in the short term.”

The effort seemed half-hearted, as he described his previous words as “consistent with what I’ve said before…. There are benefits and there are costs of where the dollar is.”

But does he really understand the benefits and costs involved? So far he has said little to ease fears about the Trump administration’s intentions in promoting a weaker U.S. dollar.

It is clear that Mnuchin sees benefits in depreciation. A weaker dollar, he said, “is good for trade.” The logic is familiar to any first-year student of economics. Depreciation, in principle, is supposed to lower the price of domestic goods relative to foreign goods and thus both promote exports and limit imports.

Much depends, however, on how traded goods are priced and how much of any exchange-rate change will actually be “passed through” to customers as final prices. The net impact on the U.S. trade balance could be considerably smaller than anticipated.

On the import side, for example, we have oil, the biggest single product Americans purchase from abroad. Since the global petroleum market is priced in dollars, a weaker greenback will have no effect at all on the cost of oil imports. And the same is true for many industrial imports as well that are typically priced in dollars, such as cars and electronics from Japan.

Conversely, on the export side, many of the products American industry sells abroad – such as aircraft or heavy machinery – are highly complex and little affected by marginal movements of price.

Costs of weakness

It is less clear whether Mnuchin understands the potential costs of the weak-dollar policy he was advocating, which could be substantial. In his view, it seems, favoring a weak dollar is not threatening to others.

“What’s good for the U.S.,” he said, “is what’s good for the rest of the world.”

But that is precisely wrong if the “good” for America comes at the expense of others, as it does when the benefit comes from weakening one’s own currency. Depreciation is a “beggar-thy-neighbor” strategy in which any trade gains are by definition someone else’s loss.

Why should we assume that foreign governments would stand idly by while market shares are being lost? More likely, they would retaliate with competitive depreciations of their own, unleashing currency war on a major scale, as we saw earlier this decade.

And perhaps worst of all, prolonged depreciation could severely erode the dominant position of the greenback as the world’s leading currency. The United States has long gained both economically and politically from the willingness of others to use the dollar as their favorite investment medium. But who wants to hold onto a sadly wasting asset? Why not switch to the euro, yen or yuan instead?

A myopic policy of depreciation in Washington could prove to be the death knell of the dollar.

Benjamin J. Cohen, Professor of International Political Economy, University of California, Santa Barbara

Shares