It’s mid-December 2016 in New York City. The sting of the presidential election has not worn off. There’s a harsh wind blowing as I’m cutting across Lincoln Center for a meeting I am drawn to, but also wary about. I have been a national political reporter since the 1990s at various outlets, some mainstream like NPR and others in progressive media. Over the years, I’ve covered elections deeply. This is not just candidates and speeches, but who can vote, who can’t, how that happens, and whether the count can be trusted. I’ve been pulled back into the vortex of our elections where, despite efforts to expand the vote and improve our system, the more ruthless and smarter forces have won again. You and I — and the vast majority of our fellow citizens — are the losers.

I’ve been here before. In 2004, I spent weeks, then months, then two years with others tracing and writing about what happened in Ohio where Republican President George W. Bush beat Democrat John Kerry. We produced a catalog of dirty tricks that Republicans have resurrected with predictable uniformity ever since. Donald Trump’s surprise victories and the U.S. Senate staying in Republican hands felt eerily familiar. Many explanations in the aftermath did not add up. In 2004, we were told a wave of rural, white southern Ohio evangelicals had reelected Bush. We looked but didn’t find them. Now a different white flock — economically struggling and lacking higher education, we were told — elected Trump. And the election was not even entirely over.

I was to meet Lulu Friesdat, a filmmaker who had been taking time off from her job as a CBS-TV producer to film the 2016 presidential recount in Wisconsin. We had talked on the phone about what she saw and shot. These were breakdowns where no one in an official role could verify to the satisfaction of observers and computer scientists what constituted the actual final count. Lulu witnessed it, filmed it, and was mortified. I posted her clips on AlterNet. She already concluded that the Democratic Party had kept the nomination from Bernie Sanders. I agreed, though we differed on particulars of its antidemocratic culture and playbook. Now Friesdat was discovering another facet of the way elections really work in America.

Her most memorable clip showed a process filled with earnest citizens; banal officials; and maddening, unnecessary complications rooted in arcane election rules. Friesdat had gone to the Racine County government center, not far from Lake Michigan. Outside the center, people were rooting for the Green Bay Packers or shopping for Christmas — but inside, the center was a world apart. Most people thought the election was over. They turned away from states certifying results, the Electoral College convention, and then Congress ratifying that vote. Interrupting this progression was the Green Party’s feisty candidate, Jill Stein, who had a legal right to file for recounts in the last three states — Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania—giving Trump his apparent victory.

Stein supporters unexpectedly had donated millions over the Thanksgiving holiday, after her legal team could not convince Hillary Clinton’s campaign to enlist some of their donors. That grassroots response was completely unexpected. Like much of America, Stein’s donors questioned 2016’s official results. They were part of 2016’s grassroots surge seeking real change, especially millennial youths. They wanted to know what happened. I’d seen the Greens file for a recount in 2004 in Ohio. That effort did not change its outcome. But it did help expose a spectrum of tactics in the fine print of voting that confirmed the GOP was committed to strategically targeting and suppressing known Democratic Party blocs. In other words, the voting process had been turned against its rightful participants.

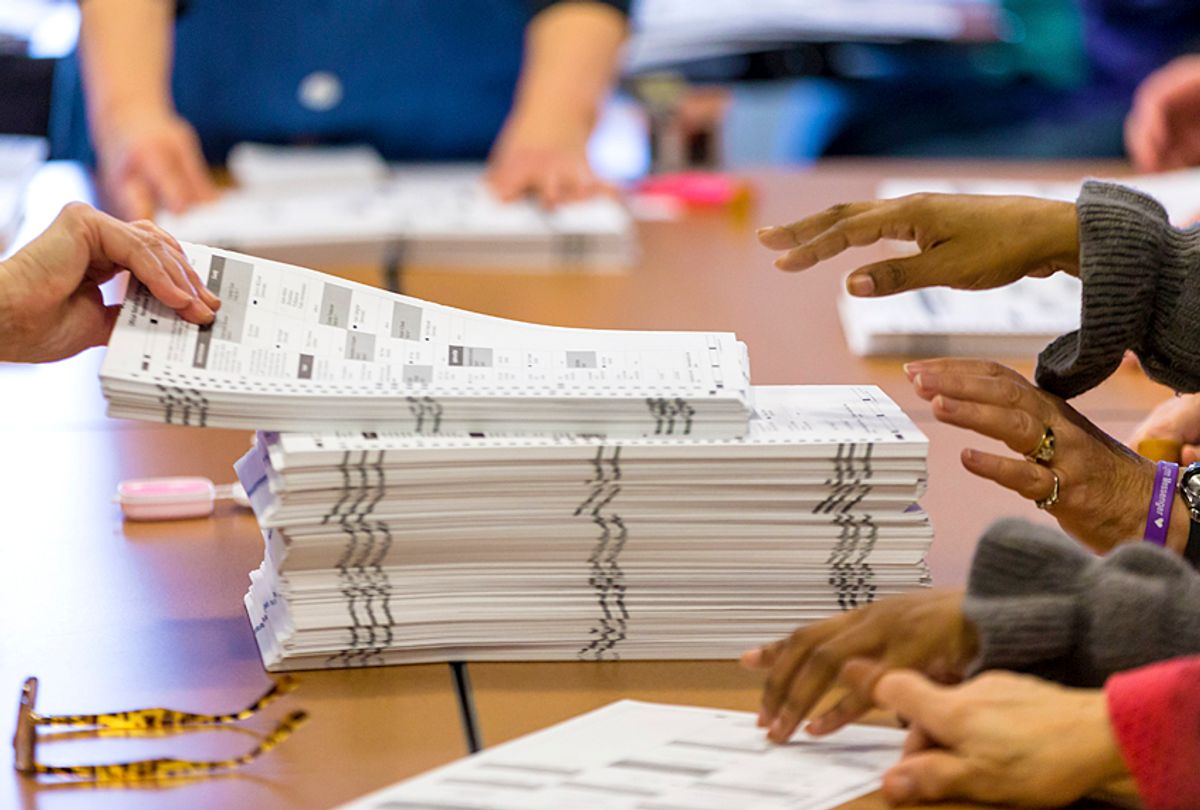

Inside the government center, which could be any election office in America, the slow methodical business of recounting an election churned. A team of middle-aged women in sweaters parsed and fed paper ballots one-by-one into an electronic scanner. Three Green Party observers, led by Liz Whitlock from nearby Mount Pleasant, stood back and patiently watched. These Greens were well-groomed citizens in their middle years, anything but wild Bernie bros from the spring campaign. They wanted Racine County to hand count its paper ballots, citing academics that said electronic scanners like those in use have implicit error rates from misreading ink marks.

They wanted to know if Trump had really won, by how much, where his voters were, or what wasn’t accurate in the process. But Joan Rennert, a veteran local official overseeing that day’s recount, was losing patience in a plodding exercise where the final outcome was unlikely to change. Across the state in liberal Madison, a judge gave each Wisconsin county the option of doing a hand recount or not. Racine declined.

So Whitlock and her colleagues devised a simple work-around. They bought manual counters, mechanical hand clickers. They clicked away as each ballot slipped into the electronic scanner, tallying how many votes were for Clinton, Trump or blank — a so-called undervote. They kept noticing their totals varied from the scanners. When Whitlock’s team saw the scanner miscount 15 votes in a 300-voter precinct in Elmwood Park, she politely asked officials to do a hand count of that precinct. That was an error rate of five percent in a contest, where statewide, Trump’s margin of victory was less than one percent. Whitlock’s request was swiftly denied.

The Greens huddled. They were upset. Whitlock then filed a challenge, a paper document that stopped the process. A face-off ensued with Rennert taking charge. Her bevy of women watched and waited, arms folded across chests, hands on their hips. Whitlock’s team bowed their heads but stayed firm. It looked like a standoff between teachers and the principal’s office. All appeared well-meaning. But it spiraled downhill as Friesdat’s camera kept rolling.

“Three observers click counted votes. The Clinton and Trump counters clicked considerable more votes than a scanner counted,” said Rennert, wearily reading aloud the challenge. “I have no idea what you’re saying except you are requesting a hand count.”

Rennert put down the paper. She looked at the room, palms up, exasperated. She said nothing.

“Do you want to ask me if you don’t understand?” asked Whitlock.

“No,” Rennert tartly replied. “Is this the purpose of a hand count? Yes or No?”

“The purpose of a hand count is to get to the truth,” Whitlock replied.

“No,” Rennert said, her hands up like stop signs. “How much is it?”

“Three-hundred,” a worker said, referring to the number of ballots.

“I don’t care if it’s five,” Rennert declared. “I am not going to do a hand count for anybody.”

I don’t have to tell you who had the final word. Nor whether the official vote count matched the hand clickers or computer scanners. Stubbornness and institutional inertia won.

This small scene points to one of the great ironies of our time. Our system of voting has increasingly subverted American democracy. The antidemocratic features in our elections are betraying the country, its citizens, and our collective future. This is a bigger problem than which party or factions win or lose — although those most responsible for this crisis, the Republicans, have triumphed.

The scene in Racine’s government center was a microcosm of the fragility, imperfections, opaqueness, and frustrations that all too often comprises American elections. The volunteers and workers weren’t bent on bad will, but they weren’t to up to the job, given its seriousness and its stakes. Their ineptitude and stonewalling were less excusable because these weren’t overwhelmed poll workers, but arms of local government that should have known and done better.

Notably, this snapshot didn’t even involve hard-core political types — the partisans, in our era almost exclusively Republicans, who deliberately undermine their opponents’ base at many key steps along the way before the vote count. I had been in Friesdat’s shoes, discovering slights that undermined the public’s expectation that every vote mattered, every voter was equal and all ballots would be counted. When I went to meet her, the unofficial results — another GOP sweep — were raw. I had not delved into the minutiae of elections for several years. I wasn’t a newcomer, but 2016 was different — and not just Trump’s ugly path.

After reporting on Ohio, I covered the 2008 election as a voting rights beat and saw how President Obama’s landslide breached the anti-voter barriers we documented. These were micro-aggressions that would have favored Republicans in a closer race had the economy not crashed that fall. These attacks are embedded in the fine-print rules of voting. They are almost always presented by politicians and regulators as neutral changes or safeguards or colorblind. In reality they shape who votes and is likely to win. They favor a status quo that is almost always the GOP’s shrinking, aging, largely white, and suburban base.

For example, restricting the forms of state-issued ID required to get a ballot at a polling place. Or adding an extra requirement on a state voter registration form that’s not on the federal form, found in every post office. Those moves block students, people of color, and the poor, just as they are intended to do. Or curtailing early voting on the weekend before Election Day, when clergy urge congregations to go to the polls. Or rejecting ballots turned in at the wrong table in a polling place. Or darker tactics such as top state officials knowingly using error-prone databases to purge infrequent voters, but not telling anyone until they show up to vote. Or deliberately segregating Democratic voters into a smaller number of urban districts and spreading out those in suburbs and rural areas when drawing political maps so that the Democrats will never win.

In 2009, I joined a team at the Pew Center on the States to modernize voter registration. After Obama’s blue wave, I felt improving turnout was the key to changing our politics. Pew’s ensuing data center included identifying all the eligible voters in a state and then contacting them and urging them to register. By 2016, it was used by 20 states and helped break a national record for registered voters. But most of these new voters were not in the swing states. Something else was going on in states that determined who controlled the U.S. House, that kept turning purple states red and was pivotal in electing the president. As I was drawn into covering 2016’s recounts, I was jarred by a series of deepening reminders that whatever progress had been made was being overshadowed where it mattered the most.

I knew what Friesdat thought in Racine. This was not the democracy we expect, not when citizens cannot verify the count. She was doing math in her head — just like we did in Ohio. If the voting machine error she saw was anything close to routine in a state with 2,976,150 presidential votes, it could mean up to 150,000 ballots were incorrectly tallied. That might negate Trump’s 22,000-vote victory. It might not. The only way to find out was not widely happening — observable hand counts. Of course, it is easy to say this is reading too much into one incident. But I, too, kept seeing a system not defaulting on behalf of voters — America’s citizens.

My moment of outrage came a few days before. In Michigan’s capital, Chris Thomas, the white-haired, taciturn, veteran state election director was lecturing reporters about his state’s recount that had just begun. Thomas has survived decades of working for Democrats and Republicans. This includes Republicans that glibly say that hordes of phantom Democratic voters are stealing elections and not getting caught, which is a knowing lie. I’d met him in Pew’s effort and thought he was shrewd enough to avoid partisan ploys. I was wrong.

Thomas cultivated a hardheaded persona. But he had also finessed an impressive work-around for people who, at the last minute, show up at polling places and aren’t on voter lists. High-stakes races always have people like that. They are eligible voters but never update their registration or bother to register. During 2016’s caucuses and primaries, Democratic Party rules and administrative barriers blocked these enthusiasts from voting. That hurt Bernie Sanders in several key states. New York was the worst, where its rules blocked anyone from voting in April’s primary that had not registered with a party six months earlier. Thomas devised a slick way to allow these impulsive people to vote while cutting red tape. Instead of giving them a provisional ballot — which isn’t counted right away because it has to be verified, he created a form with an oath. They would swear they were state residents, US citizens, eligible voters, and would vote via a regular ballot. That is unadvertised Election Day registration — a pro-voter move that Republicans have shut down in many red states.

But now, in December 2016, Thomas was on Michigan TV stating nearly 60 percent of Detroit’s ballots could not be recounted. The reason given was because poll workers had mislabeled the boxes the paper ballots were put in while cleaning up on Election night. Or the numbers of ballots listed outside the boxes didn’t match the ballots inside. Most were off by a few, often less than ten. Or seals on storage boxes did not look perfectly tight. Or the boxes were banged up. To the GOP, this apparent sloppiness was turned into accusations of ballot tampering by Democrats. Imaginary threats to the integrity of the process are what Republicans love to cite and hype — especially if it helps them win. They never put voters first and abide by the results. More than half of Detroit’s presidential ballots were deemed ineligible for the recount. Votes that might have tipped the state were taken off the table.

That conclusion was just what Thomas’ political bosses wanted. Michigan Republicans, led by the state Attorney General Bill Schuette, joined Trump’s campaign to block a recount. They ignored Trump’s rants that the voting was error prone and not-to-be-trusted until he won. They declared there was no reason to recount the state. Such double standards are predictable in this fold. They shrugged at the fact that Michigan had Trump’s closest margin nationwide: just eleven thousand votes out of 4.8 million ballots cast. Some seventy-five thousand ballots did not show a vote for president, Michigan’s secretary of state office reported on its website.

That last omission is always suspicious. That’s because people tend to vote for the high-profile races if they vote at all. Maybe some of these 75,000 ballots had presidential votes, but they were not properly scanned. If a good number were from around Detroit, which went two-to-one for Clinton, maybe Trump did not win Michigan after all. Local election activists pointed to a 1950s state law that gave discretion to election officials to examine and recount every paper ballot. But Thomas went on TV saying it would not be done. Detroit’s election director followed his cue, apologizing for the sorry state of voting in his city.

Knowing someone who could have quickly solved one of 2016’s answerable questions rattled me. Thomas and Detroit officials could have sided with that black majority city’s voters. Instead, this incident was a brazen reminder of the GOP ethic that one can never over-police the process or do too much to twist the rules in pursuit of victory. Michigan’s GOP didn’t care if a display of apparent institutional racism and voter suppression were a means to that end. Not surprisingly, they stopped the recount in court days later — much as the Supreme Court had infamously shut down Florida’s recount in 2000, making George W. Bush president.

Following the recount was mesmerizing and jarring. It wasn’t doing what a democratic process is supposed to do — provide assurances that the result is accurate. Instead, it was exposing a starker and more cynical side of elections. The answer to Michigan’s seventy-five thousand under-votes was not computer science. It was examining the vote: looking at individual ballots to see if a vote was there or not. That is straightforward. That was not the same as bringing in cyber detectives to hunt for code-altering fingerprints in voting software to see if the count is being tweaked to one side’s benefit. That’s what the Greens wanted to do in Michigan, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania. But that wasn’t to be, either.

Shares