When news of Robert Parry’s death reached me a week ago, I had to stop working for a long time. I would call it an interim of respectful silence except that it was closer to paralysis. The fight against all that is corrupt, misguided, maliciously intended and simply wrong in our national life instantly seemed still more forlorn than the sentient among us already understand it to be. One keeps on — there is no alternative. But the slope where the stone of Sisyphus rolls ever downward seems steeper now, and certainly it is a lot lonelier.

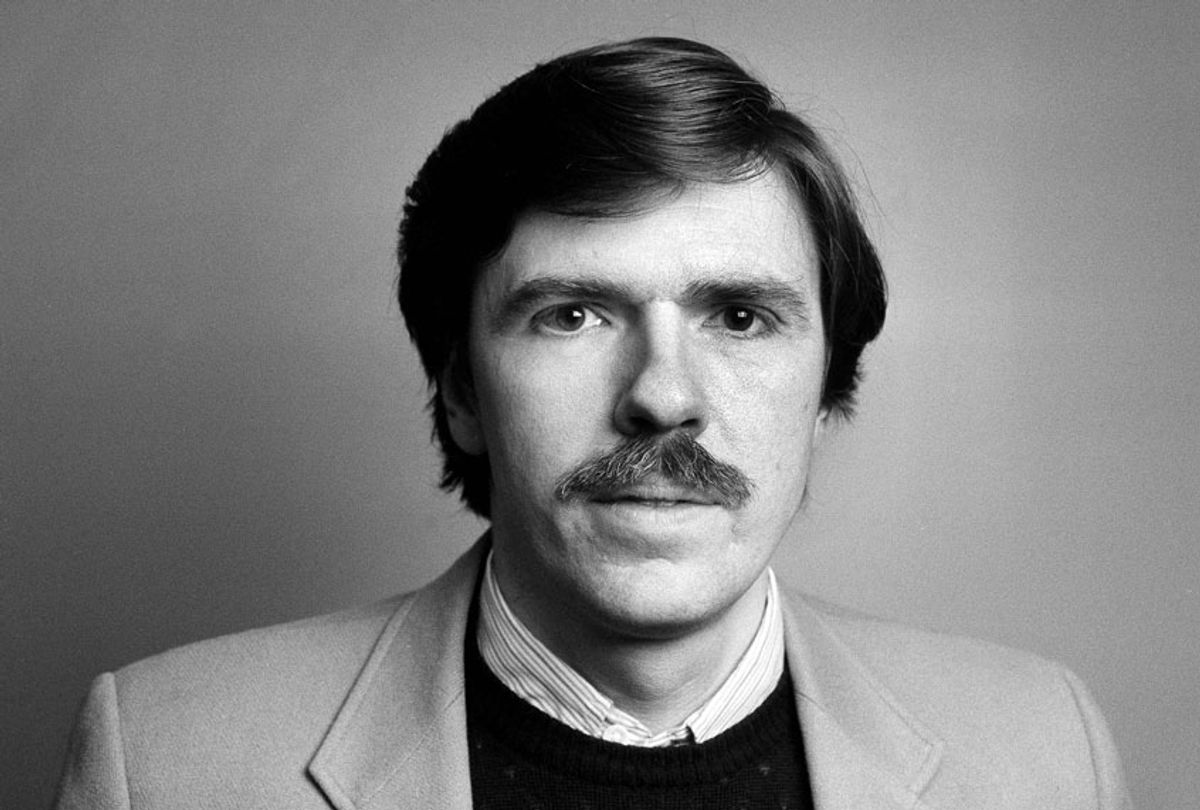

Given the expressions of grief and sorrow that flowed all week, I take it I do not have to explain at length who Bob Parry was. As an Associated Press reporter in the 1980s he broke some of the biggest stories of the decade, notably the scandal known as Iran–Contra. He went on to many more years of reportage, prizes and books (five). In 1995 he tossed it in on the mainstream side and founded Consortium News, of which he was also publisher and editor until his death. Oliver Stone, Bob’s collaborator on the 2014 documentary “Ukraine on Fire,” said it as well as many others. “Robert Parry’s death Saturday morning leaves a giant hole in American journalism,” the celebrated filmmaker said when the New York Times called him for comment.

Does it ever. I would like to devote this modest addition to the many tributes offered since Parry’s death to explain why I think this is so. It is the best I can do.

A few days after Bob died it happened that Nicholas von Hoffman did, too — at age 88 after a long career as a scourge of those multitudes in Washington deserving of such treatment. Von Hoffman did a lot of good work. He had a sharp blade of irreverence and was always good for a piercing epithet. He worked often with a delightfully savage humor. But his essential position was of a writer (as Lyndon B. Johnson would have said) inside the tent urinating out. “I think you’re mad if you come into journalism with the idea that you’re going to change things for the better. I write because I enjoy it,” he once told the ever-supercilious Newsweek. The magazine carried the quotation with a certain implied approval, as did the Times when it reproduced it in its obituary Friday. It was as if both publications sought to say, “Have fun, live on your privilege, and forget about making any difference. Nothing and nobody does.”

This was not Bob Parry’s page.

Without diminishing any of his earlier accomplishments, in my view the most important, most courageous and wisest thing Parry ever did was break with the mainstream and found the Consortium for Independent Journalism, the organization that ran the web site we read now at Consortiumnews. He had to know the size of the stone rolling down the mountain, having been a (highly critical) part of it for so long. But he understood his time better than any of his colleagues. I think Bob stood shoulder-to-shoulder with his friend Ray McGovern, the noted whistleblower and teller of truths. Actually, I know he did. We do not do things because we are certain of success, Ray sometimes says in his lectures. There is no such calculation. We try for it, certainly, but we do what we do because it is right, and we therefore understand that we must.

It is no coincidence that Ray comes to mind as I write of Parry’s importance to all of us. They collaborated frequently: Bob customarily published the open letters and memoranda issued by Veteran Intelligence Professionals for Sanity (VIPS), the organization of ex-spooks who stepped outside when achieving and advancing truth seemed no longer possible from within. They had made the same move — something I imagine never needed to be said between them. They looked at the stony path and determined to walk it. And it was on it — it is because he was on it, I would say — that Parry was able to do what I count his most consequential work. Ditto McGovern.

Returning to the wonderfully crude LBJ, these two people — an accomplished hack and an accomplished spook — shared the recognition that not much more could be done unless one stood outside the tent and urinated in. This is the core truth Bob bequeaths. There is bitterness attaching to it, given the certainty of hardship. But at this point in our story, I find that bitterness provides a certain sanctuary, odd as this may seem. Things are clarified. Where one stands is clear. There is not much question of turning back. One goes with Admiral Farragut as he entered Mobile Bay in 1864. “Damn the torpedoes,” he shouted at his quaking crew. And let us not forget: Farragut’s fleet won the day.

* * *

I liked being around Bob on those few occasions I was. He had a reserve and self-possession I admired. The last time I saw him was at a dinner VIPS gave in the autumn for Seymour Hersh, another whose name is properly mentioned in the same paragraph as Parry’s. Bob had a debilitating stroke shortly after that occasion, then two more, and these turned out to be prelude to the undiagnosed pancreatic cancer that finally felled him.

Knowing Parry but not terribly well, I think I had him a little wrong. In my read the corruptions evident in our media were what drove him. He lived on his indignation, then (as I do). This was a big part of it, maybe the largest part. He detested the evaporation of integrity and honesty in the mainstream press. “False narratives,” “fake news,” the Russiagate mess, the soft despotism of liberal hysterics — these seemed to bring him somewhere close to seething (as they do me). He knew first-hand the “harsh criticism even from friends of many years for refusing to enlist in the anti–Trump ‘Resistance.’” (And so do I.)

But there was more to Bob’s work than this.

Nat Parry, one of his sons and his longtime collaborator at Consortium, who I gather will now run the site, published two pieces last week worth seeking out. One concerned his father’s legacy and Consortium’s future. The other is headlined “Outpouring of Support Honors Robert Parry.” In the latter piece Caitlin Johnstone, the Australian commentator whose voice carries across the Pacific well enough, offered this:

I would suggest that it is [an] underlying devotion to the plight of mankind which allowed Robert Parry to become Robert Parry. It wasn’t his connections, his political opinions, his ideas, or even his raw talent; it was the fact that he cared so much. The fact that he couldn’t dissociate himself from the horrors of this world, the evil things humans are doing to one another and the omnicidal trajectory we appear to be headed along. He saw it all, he felt it all, and he let it move him.

This kind of talk is unusual among correspondents. It comes over as a touch angelic. You get responses such as Nick von Hoffman’s, quoted above. Get the story, get it right, file the story, move on to the next, all good fun: This is more the norm. But I am with Johnstone on this one. The craft, if one has a passion for it, yields great pleasure. But honestly, that is not finally the point. Johnstone lifts a long-undisturbed rock. Under it we find the question, like a message in a Chinese fortune cookie: “What are we doing this for?” it asks. Bob may not have agreed, and his son Nat may not now, but I think this question was implicit in everything Bob wrote and published at Consortium.

Now it is ours — we press people, we readers — to keep this question alive. The best way to do this, in my read, is to understand our moment as Parry père did and Parry fils may. The craft needs a reinvention. It needs to re-situate itself in relation to power. This is the first imperative, to make itself again (although I am not into “golden ages”) an independent pole in the polity. Not separate from this, our media need to remake their relations with readers and viewers, too. I do not mean speak for them. No: They can do that for themselves. I mean speak to them in plain, clear language, as against at them, as if we in the media are the bearers of coded messages from the circles of power we are supposed to maintain a professional distance from.

I mean to say that what Robert Parry wrote and published and how he did so are of approximately equal importance. At the horizon they are not separable, indeed. I think Consortium, along with some other publications, is at the front edge of a transformation in American media that has a long way to go yet. The first word of Bob’s death reached me via a note Max Blumenthal sent out last weekend. Max writes for one of the sites I allude to here, and he has a cutting voice second to nobody’s when it comes to getting to the truth of things. He is my point made flesh: In the end, we will find there is no such thing as “alternative media.” There are only media — variously endowed, variously professional, variously ethical, variously independent or corrupted. I imagine Bob Parry would insist on this.

“Journalism will kill you,” H.L. Mencken once said, “but it will also keep you alive.” Robert Parry died of natural causes, if too young. But knowing him only a little, it seems to me his faith in the power of the craft he spent his professional life practicing was indeed what gave him life.

Shares