Okay, time to fess up. Much like Thomas De Quincey, almost 200 years ago, became hooked on opium and went on to write about it, I have devolved into an Advil addict here in 2018 whenever I see a Social Justice Crusader attempting to police what art I cannot partake of and be enriched by.

This happens often, but not as often as it could, if SJWs actually knew anything about art, which is rare. That’s bound to be the case when your existence and sense of self is predicated on pointing at things you wish to tell others to avoid, thus making real connections exceedingly difficult to come by, thus feeding your depression and self-loathing. An emotionally violent and vicious cycle that ultimately creates a prevailing numbness, which leads to an absence of nuanced thought, legitimate empathy, love and self-love, and us being where we are as a society. It’s that. It’s not your elected leaders. Everything stems from us.

Nothing is more of a surefire migraine starter for me than people white-knighting it with art. I pre-dose these days with my gel caps before reading some articles, which I’d be better off avoiding. Look, if you care about something, and you are knowledgeable on the subject, I am all for you shouting from the mounts, but learnedly, thoughts/theories/conclusions totally oppositional to what I believe.

I can’t imagine there’s a person who does more Beatles-related work, for instance, than I do, and if you have a compelling argument why “Abbey Road” is dreadful, which I could not agree less with, I’d love to hear it. It’d entertain me, make me think, make me respect you. My loyalty is to truth and beauty, but there are all kinds of angles from which we can approach those twin peaks.

What galls me, though, is when people call out one work of art, based on something they know, or think they know, about the life of the person who created it, while letting every other artist skate — as in, pass on by, unchecked — simply because these geniuses of society have never read a biography in their lives.

Because if you’re going to do the whole “art is not separate from the artist” thing and adjudicate on what people should partake of based on that, you need to stop going to the museum, never watch Turner Classic Movies again, never listen to the Beatles or just about any rock band, put down that classic novel, ditch Miles Davis and jazz, and if you think the people who made most of our best classical music were patron saints of SJW-dom, you are fooling yourself. This is censoring based upon an individual’s ignorance and, in following, hypocrisy. It’s also killing culture incrementally every day, though there is going to come a moment when it snaps back in the other direction. Art lasts; SJWs, who are so rarely about equity, are flushed, their anemic, would-be souls with them.

Which brings us to Leni Riefenstahl. The Criterion Collection — which everyone likes, right? — has just released an enormous box set totaling more than 50 films, all centered on the Olympics. I tend not to like the Olympics that much. It’s sports-lite, in some ways. I’m into Jessie Owens and the 1980 U.S. men’s hockey team, but often the Olympics serve as the kind of sports you get into if you’re a hipster who only likes tennis — a rich person’s sport where people virtue signal by conversationally referring to Federer by his first name — and the Kentucky Derby, which are ideal for hipster parties where at least two people have “Paris Review” tote bags. In short, dabbling fare for the people who always had a note to get out of gym class.

Having said that, I am aware of no finer sports film than Riefenstahl’s 1938 “Olympia,” which was so expansive and exacting as to require two parts totaling 226 minutes, and which is included in this box set. I’ve been watching it since I was 15 years old, mesmerized by what is tantamount to a Cubist-naturalism take on sports — which you wouldn’t think possible — and cinematic techniques that dazzled me in the same manner that Orson Welles did when I first saw “Citizen Kane.”

Herein lies the controversy, and why it took some pelvic-region fortitude for Criterion to include this film: We are not exactly sure to what extent Riefenstahl may have been a willing member of the Nazi party. Let’s put it this way: If you want to think she was, you can certainly read a number of facts that way, just as if you wish to believe otherwise, there are facts to tip the scales in the direction you wish.

She may have had a crush on Hitler. She shot “The Triumph of the Will,” which certainly is not anti-Nazi — and was a big influence on “Star Wars,” actually — but I’m also not sure, this being 1934, how much she might have known, could have known. Plus, sometimes artists are so locked up in making art that a kind of willful ignorance occurs, where anything extraneous to that art-making is pushed out of the consciousness.

I’m that way. I could not tell you what “Shades of Grey” is for the life of me. Is that the same as Nazism? Obviously, there’s hardly more of a fatuous claim you could make, but my point is that I have no clue what passed through Riefenstahl’s mind, so far as her inward creative process went, even after reading just about everything written on her.

I also know that there are a lot of would-be “tough guys” — I’m using the term as we all know how it means, not differentiating in the relative toughness of genders — who now talk, and blog, and endlessly palaver, about how they would have acted differently at some point in history, when everyone around them was acting the same way, which is BS, as these people are almost always acting the way everyone around them in their lives acts right now. Which empowers them. If everyone else acted a different way, well, boy howdy, they’d get on board with that right quick. It’s hard to be the lone dissenting voice, or one of them, in the other team’s stadium. I guess. I don’t know. And, when I watch “Olympia,” I really don’t care.

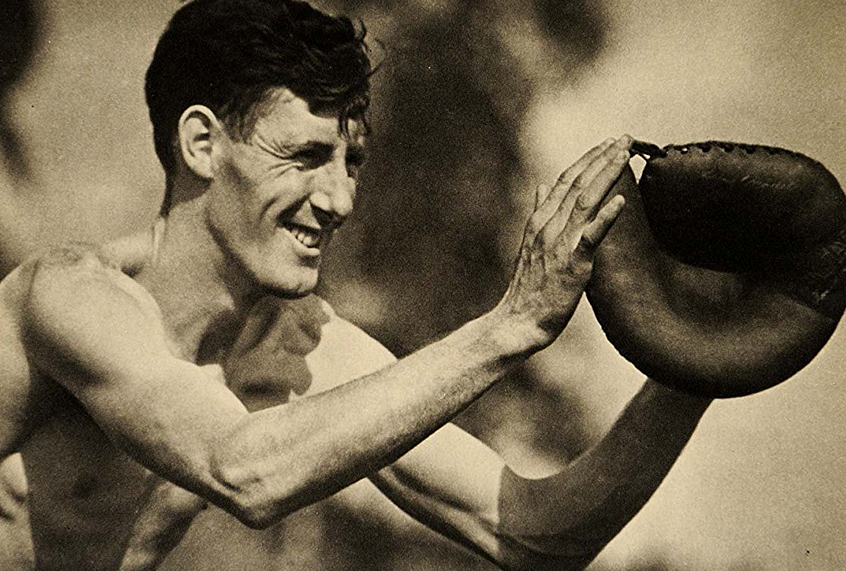

Riefenstahl shoots Jessie Owens with the rapture of the poet’s eye, a poet in love with Owens’ own artistry. We are lucky we have this footage, the epitome of athletic grace on the big screen, and that must have burned Hitler’s ass. But fear not: It’s cool and easy to fall under the spell of this film if you’re not a sports person, and I get how people inclined to what we perceive as quieter, more contemplative pursuits can find sports off-putting, which often takes the form of a kind of intimidation.

We feel that we will not be able to penetrate the athletic world, maybe, and be successful in it, because success, so often in sports, is not based on anything subjective. It is talent-based. That is why I value sports like I do in the present day as one of the last battlements of meritocracy. Publishing is certainly an anti-meritocracy. I don’t believe there is anyone who has ever walked this earth, for instance, who actually thinks Lydia Davis is any good at writing and would wish to be stuck alone with only her drivel on a desert island, but if you’re in the in-crowd, this is what you pretend to believe, or work to get yourself to believe. It is what awards are given to. If only lies came encased in gelatin-coatings like pills.

“Olympia” makes sports universal in a startling way, though, by extending the rules of the game — to borrow a phrase from Jean Renoir — to transcend what happens on the pitch, race track, or in the pool. The reason the NFL is so successful is because it has turned a sport into a form of non-sport. That is, to appreciate, say, hockey or baseball, you need a kind of understanding as to what it means to execute a power play with the center cuing everything from the bumper position, or just how valuable it is that your nine-hole hitter hit behind the runner on second to move him to third with less than two outs.

The NFL has become gladiatorial. It’s about big passing numbers, big hits, hating the Patriots. It’s more broad, less nuanced, in its presentation. Of course, this is in appearance only, as football is pretty damn complex at the level of what is really going on, but Riefenstahl was even more successful with her alchemy in “Olympia.”

She is a painter of faces, of desire, of endurance, and from the faces these emotions modulate to play anew in calf muscles, beads of sweat, slumped shoulders when defeat sets in, that quick intake of breath upon the realization that there will be more games in the future, and Defeat, the pesky cousin the Reaper, may be bested after all.

She blended the long take with quick cuts like an editing virtuoso. I don’t think it’s a stretch to say that the way Riefenstahl cuts in “Olympia,” with some of them being timed to heartbeats, it seems, was an influence on Richard Lester’s “A Hard Day’s Night” and future music videos.

She shoots from all angles, including from down low, as Welles was fond of, with that juxtaposition of fluid camera work and chopping-cuts fracturing, then remodeling, what another director would have turned out as well-worn images. This is Cubist, in a sense, splintering the whole so as to better reveal a larger, more impactful whole, but it’s also as congruous as an air current drying a sweaty brow.

Watch the famed diving sequences to get a feel for Riefenstahl’s balletic, painterly, paradoxical mastery where the master shot and the cut-in are one, with the past, the present, the oncoming, the close, the far, the beside and the between all gloriously — learnedly — superimposed. That should not be possible, but this is a brilliant artist. It’s a cinematic sleight-of-hand, but one, again paradoxically, with no trickery in it that never departs from the real and the truthful in changing how we look at the world and wonder what else we may have been missing and not seeing, as it were, not as we wished, or assumed, it to be.

It wouldn’t kill you to do the same thing with Leni Riefenstahl and “Olympia.” Leave her out of it, if you wish, or tar her in your mind as you see fit, if that helps you out, I guess. I would say it probably doesn’t at all, maybe work on that here in the new year, and take a gander at yourself the way she observes those bodies piercing the water. Be more plink, and less plunk, and bathe in the art we’re lucky enough to have. It’ll get the grime of ignorance off of you and you’ll swim better, in the metaphorical sense. Hell, maybe in the physical one, too.