One of the great gifts of American life is its regional diversity, full of separate state identities. Modern technology, and the mass media, have the unfortunate tendency of muting that diversity in the creation of a repetitive and banal monoculture.

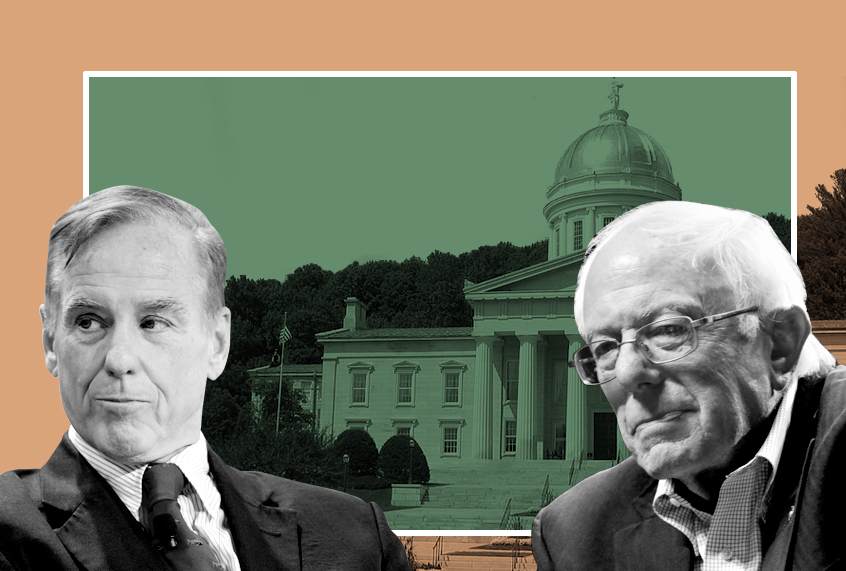

Vermont, home of John Dewey, Bernie Sanders, and Phish, is American to the bone and contains fascinating multitudes for those willing to look.

Bill Mares, a former reporter and member of the Vermont state legislature, has collaborated with Jeff Danziger, an award winning political cartoonist, to help Americans acquire a picture of Vermont political culture, one that is especially revealing in the aftermath of Donald Trump’s election.

Their book, “The Full Vermonty: Vermont in the Age of Trump,” is a rollicking, humorous and insightful exploration of the unique qualities of a state that, in many ways, is one of the union’s most progressive, even if it is largely rural and mostly white. A contradiction of demography and ideology captures the essence of what makes the story of Vermont feel essential in the maddening quest to understand America and react intelligently to the still surreal presence of Trump in the White House.

“The Full Vermonty” includes chapters from a wide variety of contributors – politicians, journalists, activists and philosophers. I recently interviewed Mares over the phone.

In one of the introductory chapters of the book, you explain that you were searching for some utility of citizenship in the aftermath of Trump’s election, and since writing and editing are things you do well, you thought you could do them in service of the cause of your country. What is your ambition for the book, and is that ambition troubled by the worry that you are preaching to the choir?

Well, I’m very aware of preaching to the choir. Let me answer the first part in a roundabout way, though. I’m currently writing a book on beekeeping in Vermont. In some way, the purpose is similar, because we don’t expect the rest of the country to follow Vermont’s way of beekeeping, but we think it is a distinctive story, and no one else has done this kind of book. So, we want people in other states to take the lead and do their own book. The ambition is the same with the political book. I know Vermont. I grew up in Texas, but I’m not going back to Texas to do this kind of book. I’m not going to Indiana. Now, one of the treasures of the book is that we have so many different types of people who have contributed chapters with their own views. Yes, in a certain sense, we are preaching to one another, but one of our characteristics is trying to sort things out in a generous community manner. That’s a hallmark of town meetings. So, we aren’t aiming to just satirize and criticize Trump, but we are trying to articulate ways in which a state or community can change.

I’ve never visited Vermont. My impression of the state comes entirely from reading and speaking with people who do have a close connection to it. One of its fascinating elements is that, according to demographic and geographic category only, it fits the profile of right wing, Trump country. It is largely rural, white and working class. However, it is also one of, if not the most progressive states in the union. Can you explain that dichotomy?

Yes, of course, but first it is important to acknowledge that 90,000 Vermonters did vote for Trump. It was a much higher percentage voting for Clinton, but 90,000 did vote for Trump, and they were distributed largely in the rural parts of the state. I was just in a bookstore with one of the co-authors, Steve Terry. He knows the state much better than I do, because he once covered state politics and was an aide to former Governor George Aiken. He said that Burlington is a wonderful place. It is an economic driver, and there are a few other pockets that are similar, but most of the state, like Maine, is poor. Certainly, Bernie [Sanders] has tapped into voters on the left, because of his progressive views, but he also has support from the right, because he refused to support the assault weapons ban. The NRA loved him for it. [Note: Politifact reports that Bernie Sanders has supported, and voted for, various measures to ban assault weapons since 1993.]

Bernie is someone who can appeal to both right and left, and I’d love to see the numbers on how many Bernie supporters voted for Trump . . .

One study [the Cooperative Congressional Election Study] indicates that one out of ten voters who supported Sanders in the primary voted for Trump. If those calculations are accurate, it was more than enough to put Trump over the top.

For several reasons, I’m not surprised. Now, back to your question – Vermont has gone through quite a social revolution since the 1960s. Prior to that, there had not been a Democratic governor in 100 years. Then, Phil Hoff changed all of that, and he rode the wave of Back to the Land people, of which my wife and I were a part. We came here in 1970s, and I wrote a book called “Real Vermonters Don’t Milk Goats.” It was about that shift in the 1980s when the flatlanders [Vermont slang for outsiders] took over the state. That period was the end of the tension between the people from elsewhere and the real Vermonters. Now, real Vermonters are almost an endangered species.

So is that what produces the progressivism of Vermont?

Yes, most of the people who moved to Vermont were already pretty liberal, even far to the left. In the 1960s, even Vermont’s Democrats were more like moderate Republicans. Then, the people who moved here from other places, like me, started pushing the Democrats more to the left. When I was in the state legislature in the early 1980s, it was the first time in 40 or 50 years when the Speaker was a Democrat. And that had solidified the influence of people from away. The transformation was gradual, and once it started it took 20 [to] 25 years.

What insight can organizers on the left draw from that story and Vermont’s political culture as it exists now?

Oh, man. I think that the people like David Zuckerman, our Lieutenant Governor, and others who coming out of the Bernie tradition are very conscious that they have to appeal to a broad spectrum of people within this state. Now granted, it is very white, but there is a range of views, and they have learned or have developed an instinct for persuading more quietly, not hectoring the audience and not preaching to the choir, except when a choir is assembled for them to preach to. They acknowledge it is a politically diverse state, and they campaign accordingly.

Now, if we look at Bernie. He’s certainly been consistent throughout all his years, and he is passionate. So, maybe passion and consistency is the message.

I like that – “passion and consistency.” It makes me think of Howard Dean, another Vermonter. The first vote I cast was for Howard Dean in the Democratic Party primary. Dean and Sanders are, in some ways, quite different, but what they share is that in their respective primaries they were both the candidates with the populist and progressive energy. Neither one prevailed, but is there some kind of Vermont characteristic that gave them both similar energy and ability to inspire?

Politics is still, by national standards, a very modest thing in Vermont. There’s almost no chance that national politics diminishes what you are in Vermont. So, what you are in public and on a rostrum is pretty much what you are in your own living room. Because Vermont is small, and mostly small towns, you can’t triangulate different behavior: I-O-Us to different groups and money bags. It is retail politics. You have to go to the chicken pot pie suppers and make your pitch. The freedom with which politics is carried on in Vermont allows people to stand up quickly, consistently and not have to constantly go though analysis of, “what can I say here? What can I say there?” They can just be – they almost have to be – themselves.

One of the writers in the book claims that Vermonters are going to be fine following the Trump election. They will continue to talk in the coffeehouses, diners and bars like they always do. You mentioned that 90,000 Vermonters voted for Trump. Is the state dealing with the same intense polarization and political hostility playing out across the rest of the country?

That insight is from Christopher Louras, who was mayor of Rutland, and lost his reelection, because he supporting bringing in more refugees from Syria. So, that is a reflection that there is intensity of bigotry here too. Now, to your question — no, we aren’t with daggers drawn. It is a little different here. Jeff and I have been speaking at bookstores, and the only time we seem to take heat is from the left. [Laughs.] They say, “Why are you only going after Trump? Why not Wall Street? Sell-out Democrats?” There is some animus, but because of the communal quality here, it is pretty soft.

Speaking of other writers — and I don’t want you to misunderstand me — you are a great writer, but having a diversity of contributors does strengthen the book’s appeal, because it gives a better impression of the state.

I wouldn’t have done it alone. I’m overjoyed to be amongst this group of wonderful people. They all have something important to say. They make it a great buffet of seriousness and satire.

So, how is Vermont reacting on the ground to all of the madness visible in D.C.?

Well, I’m no longer in the legislature and I’m no longer a reporter. I tend to spend most of my time with my family and my honeybees, but I’m not entirely isolated. The people who were dismayed after Trump’s election are even more dismayed. I think he is, consciously or not, the very notion of American government. I thought it would be bad, but not as bad as it has become. I’m not going to write another book of this sort, but I’m looking for other ways to express my dismay, [to] prevent myself from throwing up my hands and giving up, and we in Vermont are working hard to find and create signs of encouragement. So, for example, I’m on the board of the Vermont Digger, a digital newspaper. We have 15 reporters around the state. It is all Vermont stories, but we do have the occasional column on national affairs. To be on that board gives me daily satisfaction. Even though it doesn’t directly cover national news, it is another engine to enable, excite and encourage other people in other states to do the same thing. This service, and this hope to keep journalism and storytelling alive, gives me satisfaction. Few of us are on the frontlines, but we can all throw out a few auxiliary shells.