Michael Marquesen first noticed about a year ago that fentanyl, a dangerous synthetic opioid, had hit the streets of Los Angeles. People suddenly started overdosing after they shot up a new white powder that dealers promised would give them a powerful high.

“In Hollywood, they’re like ‘Everybody’s dropping . . . everybody’s overdosing!’” said Marquesen, director of the Los Angeles Community Health Project, which provides support services for people dealing with drug addiction.

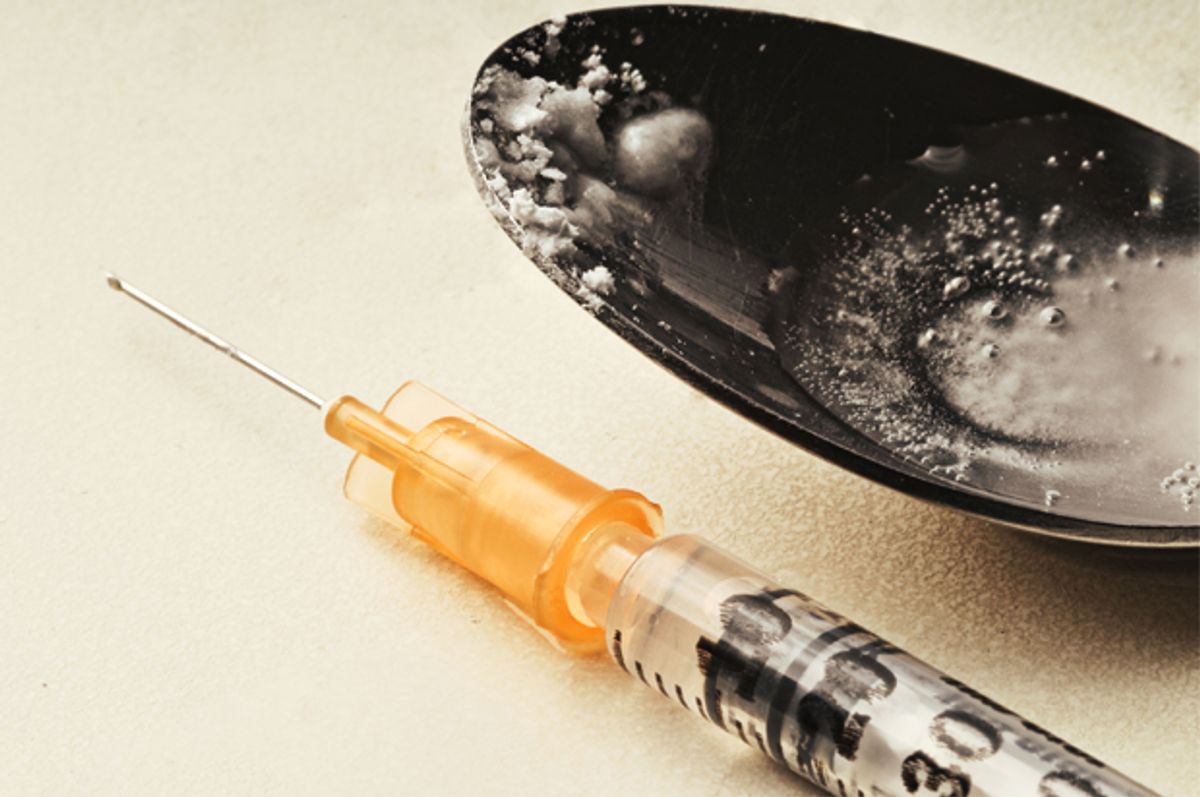

The white powder was easily distinguishable from the black, tar-like heroin that is common in California, and users initially believed it was high-end heroin. But it was fentanyl — 30 to 50 times more potent than heroin — said Marquesen, whose group runs a mobile needle exchange out of a white van, serving drug users all over the city.

The deadly fentanyl wave sweeping the East Coast and the Midwest has arrived in California. The number of deaths from fentanyl in the state, though still a fraction of those seen in some other states, has spiked in recent years. And state health officials have responded with a proactive but experimental policy: Since last May, they have supplied needle exchanges with rapid-response test strips that allow drug users to determine if their next high is contaminated with the potentially fatal opioid.

It’s hard for drug users to know exactly what is mixed into their supply, because dealers don’t tell them — and often don’t know themselves. Needle exchange workers say the strips have revealed the presence of fentanyl not only in white powder form but also as an additive to black-tar heroin and even in such non-opioids as methamphetamine and crack/cocaine.

Officials hope that if people know the dangers lurking in their stash, they’ll be more careful to protect themselves from accidental overdoses.

The idea of using the strips to test for fentanyl started at a publicly funded needle exchange in Vancouver, British Columbia. The state of New York also makes public money available for needle exchanges to buy the test strips. Eight New York exchanges, a third of the total, supply them to drug users, according to the state’s public health agency.

Last fall, Marquesen’s needle exchange started handing them out from the white van, along with a brief lesson on how to use them. Eleven California needle exchanges, from Eureka to Santa Barbara, have ordered the strips so far, state officials said.

Kelly, a 44-year-old heroin user in Los Angeles who withheld her last name because her family doesn’t know about her addiction, supports the use of test strips. She nearly died from an overdose of heroin, which she later learned had been spiked with fentanyl.

“There’s dealers who are trying to make their stuff better because it’s garbage,” said Kelly. Those dealers don’t tell their customers about the fentanyl in their drugs, she said, and that puts them at grave risk.

Fentanyl and other synthetic opioids killed 324 people in California in 2016, a jump of nearly 50 percent from 2015 and more than double the toll of five years earlier, according to preliminary data from the California Department of Public Health. The most recent spike is attributable to fentanyl, which accounted for almost three-quarters of those 2016 deaths, the department said.

The California figures still pale in comparison with other states. In New York, almost 1,100 people lost their lives to fentanyl and other synthetic opioids in 2016, twice as many as a year earlier, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In the much smaller state of Maryland, over 1,100 deaths were fentanyl-related in 2016, more than triple the number of the previous year, according to that state’s health department.

In Ohio, nearly 2,500 died from fentanyl and related opioids in 2016, double the number of the year before.

Accidental overdoses involving fentanyl were blamed in the deaths of both Prince in 2016 and Tom Petty in October.

In San Francisco, needle exchange workers and users say the ability to test drugs has changed behavior.

“People are much more cautious if they know there’s fentanyl in it,” said Patty, who didn’t want to give her last name because of her heroin and crack use. “Honestly, nobody wants to die.”

But some experts urge caution in using test strips, noting the strategy is still experimental.

Sold for a dollar apiece by BTNX Inc., a Canadian company, .they are designed to test urine and have not been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for use on drug samples, a BTNX spokesman said.

Dr. Karen Mark, chief of the California public health department’s Office of AIDS, said all the evidence suggests that the strips effectively detect fentanyl.

But Dr. Dan Ciccarone, a professor at the University of California-San Francisco who researches drug abuse, noted that the strips show only whether a sample contains fentanyl, not how much — so there’s no way to know if it’s a deadly dose. The strips are also too sensitive and could be yielding false positives, he said. That may not be such a bad thing per se, he said, but drug users might stop using them after a series of positives.

Despite reservations, many experts say the severity of the opioid epidemic justifies California’s unproven approach.

“The crisis situation that we find ourselves in . . . definitely calls for a lot of nimble and innovative responses,” said Leo Beletsky, associate professor of law and health sciences at Northeastern University in Boston. “We’re going to see more fentanyl in our drug supply in coming years.”

Shares