In 1965, Pete Townshend told a reporter from the English pop music weekly Melody Maker “[The Who] play pop art with standard group equipment. I get jet plane sounds, Morse code signals, [and] howling wind effects.” These nonmusical elements, commonly referred to as noise, when inserted into a pop song, create an aural collage (collage being an approach to fine art favored by many pop artists and dadaists) that challenges and disrupts order. Although he would not publish these words until 1977, French theorist Jacques Attali articulated a similar sentiment reflecting pop artists’ contention that theirs was a lived experience, one that included music: “Music is more than an object of study: it is a way of perceiving the world; a tool of understanding . . . [it is] thus necessary to imagine radically new theoretical forms, in order to speak to new realities. Music, the organization of noise, is one such form. It reflects the manufacture of society; it constitutes the audible waveband of the vibrations and signs that make up society. An instrument of understanding, it prompts to us to decipher a sound form of knowledge.” I have no way of knowing if Jacques Attali ever listened to "The Who Sell Out" (I’m assuming he didn’t), and I’m guessing that 60s pop art was not on his mind as he wrote, but both he and Townshend, each in their own discursive way, argue that music as pop art is commodity, spectacle, and ritual. But whenever pop music is relocated into a different position within this cultural discourse, a new discourse is created and a different message is conveyed. Townshend said as much to a reporter from the Observer in 1966: “From valueless objects—a guitar, a microphone, a hackneyed pop tune, we extract new value. We take objects with one function and give them another. And the auto-destructive element adds immediacy to it all.”

Auto-destruction was the physical manifestation of the Who’s pop art music, not to mention an intellectually palatable euphemism for smashing up equipment. The oft-told story is that it began as a one-off—a pissed-off Townshend, unable to control the feedback emanating from his Rickenbacker, and egged on by some friends from art school, banged the guitar against a low ceiling, accidentally breaking the neck. Instead of shock and dismay, Townshend’s reaction was to finish the job. “I had no recourse but to completely look as though I meant to do it, so I smashed the guitar and danced all over the bits. It gave me a fantastic buzz.” (Marsh, 1983) Though Lambert initially opposed the idea for practical reasons—constantly replacing gear was bloody expensive—it made for great publicity and cemented the band’s reputation as the most exciting (and potentially dangerous) live act in England. “It was like seeing a piece of pure energy, pure raw energy,” Roy Carr enthused, “if you could get just pure energy and put it in a form and operate it—that was the Who.” (Barnes, 1982) Even Gustav Metzger, who’d introduced Townshend to the concept of auto-destruction and the outré works of the Gutai Association, became a fan, often asking the band to perform at Ealing. Townshend and Lambert gave it a pop art spin and, as Dave Marsh notes, were able to meaningfully contextualize what seemed to be wanton excess: “[Auto-destruction was] the fury of rock and roll’s attempt to exorcise the world of all of its impurities. In this sense, guitar-smashing was not just an exercise, it was the climactic moment of what the Who’s stage presentation was all about—probably the only appropriate one conceivable.” While such an analysis mollified the art school crowd, to Keith Moon it was all a bit of fun, an old-fashioned, Shepherd’s Bush knees-up: “I don’t know why we do it. We enjoy it—the fans enjoy it. I suppose it’s just animal instinct.”

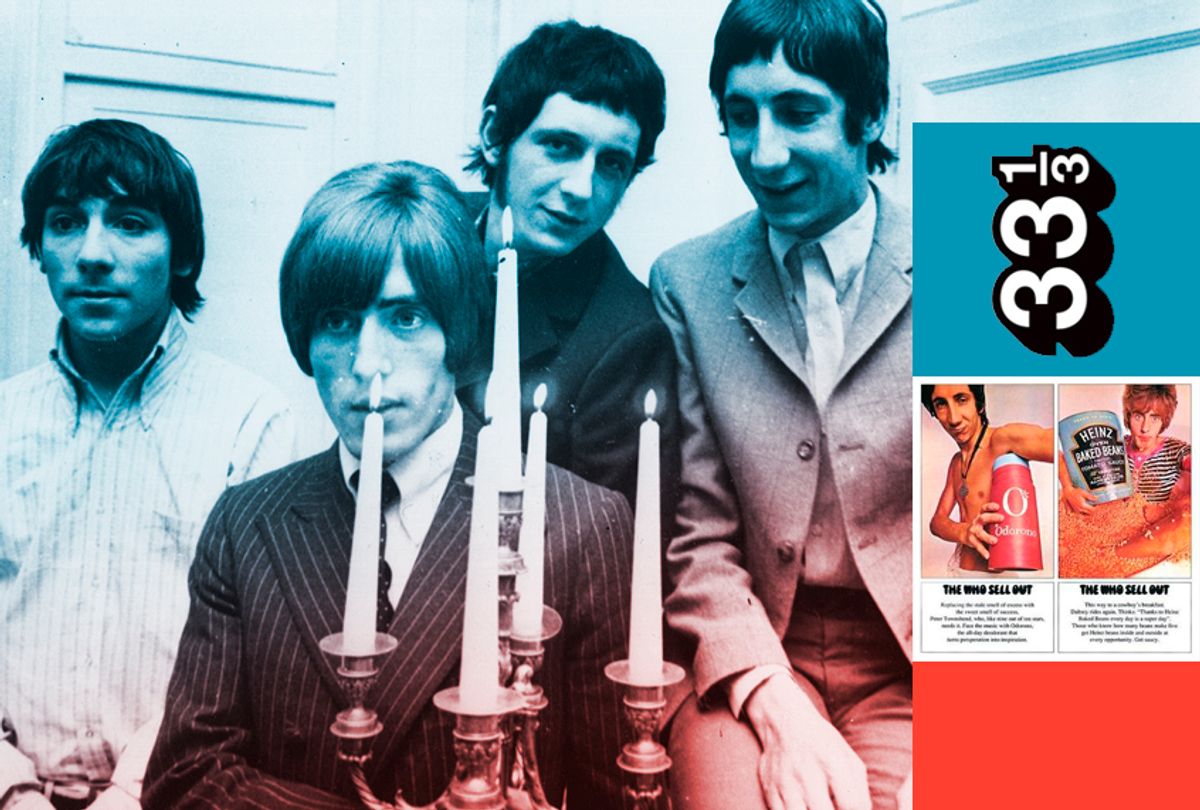

When the Who released their maximum R&B, proto-punk debut album "My Generation" in December 1965, mod was, for all practical purposes, drawing its last breath. Thoroughly co-opted by the mainstream culture industry, it had gone from subcultural phenomenon to marketing strategy, a fashion impulse sold to those who could afford the look. A year later, when "A Quick One" was released, the Who, while still retaining some modish inclinations, had been transformed into a full-blown, ear bleeding, auto-destructing, rock and roll pop art experience. And while "A Quick One" suffers a bit from well-intentioned artistic democracy (Daltrey’s and Moon’s contributions proved they were negligible songwriters), Townshend’s songs (especially the title track and the dazzling “So Sad About Us”) indicated that at 21, he was rapidly maturing into one of England’s most expressive and audacious rock artists. More importantly, the album’s release unequivocally stated that the Who rejected complacency and embraced change, not simply to follow trends, but rather to accommodate Townshend’s considerable breadth of ideas. There was not another band like them, but they were not the only ones testing the limits of rock songwriting and performance. The Beatles and Stones, still the benchmarks by which virtually every English band was judged, were always upping the ante, as were the Kinks, but the landscape now included Pink Floyd and Cream, bands more concerned with artistic expression and instrumental virtuosity than mere chart success. There was also Jimi Hendrix, who’d arrived in the UK from America in the fall of 1966, debuting to rapturous acclaim, seriously threatening the Who’s hard-earned reputation as England’s most impressive live act. Further problematizing the band’s plans for world domination was that their American record label, Decca, was preternaturally dense not only about the Who, but rock and roll in general. In January 1966, Chris Stamp flew to New York to whip up a little enthusiasm for the band amongst label management, only to be greeted with a lack of interest, commitment, and direction. Worse still, was the situation with Shel Talmy, the American recording engineer/producer of My Generation with whom Kit Lambert had struck the Who’s first (and worst) contract. Seeing himself as the second coming of Phil Spector, Talmy treated artists as puppets through which he would channel his “formidable” production skills. Lambert and Stamp, with considerable help from powerful music entrepreneur Robert Stigwood, finally extricated the Who from Talmy’s death grip, but at a cost. For the next five years he would receive a five percent royalty on all Who recordings, a period of time that would see the release of both "Tommy" and "Who’s Next."

From mod to pop art music to the emergence of psychedelic bohemianism (all part of a burgeoning rock and roll-oriented, youth-driven culture industry), London was, from 1966 through 1967, in a near-constant state of flux. It was a time of intense creativity and cultural instability, when the city went from black and white to color and was poised on the cusp of the “Great Leap Forward in terms of the extension of the power of the imagination into myriad cultural realms.” It was under these circumstances that the Who made their great leap forward, touring America and recording "Sell Out."

Shares