Excerpted with permission from "Lincoln and the Irish" by Niall O’Dowd. Copyright 2018 Skyhorse Publishing, Inc. Available for purchase on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and IndieBound.

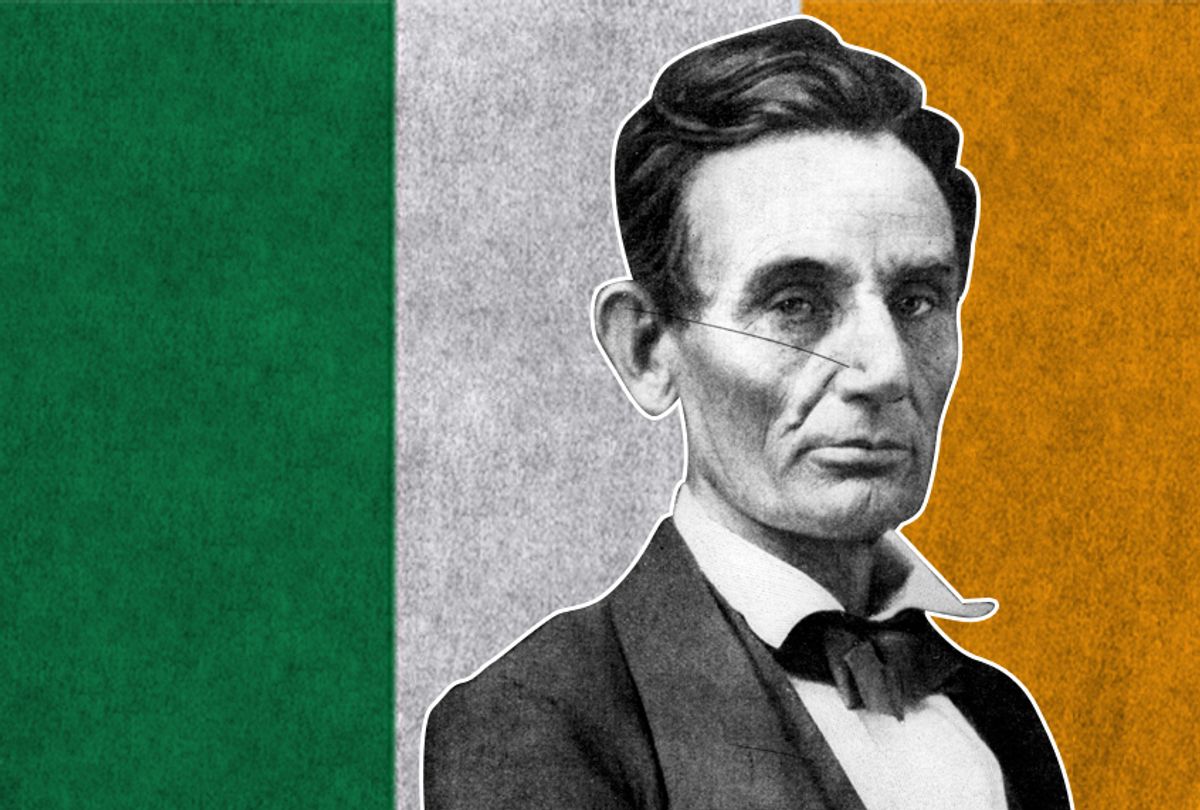

“Write what should not be forgotten,” advises Chilean American author Isabel Allende. With that in mind, I began this article about how the Irish were a huge part of Abraham Lincoln’s life and successes.

There have been 15,000 books written (and countless articles) about Abraham Lincoln, more than on anyone in history, bar Jesus Christ. Of paramount interest to me is the Lincoln-Irish connection, which to my knowledge no work has conclusively examined. There have been many books on the Irish and the Civil War, but not specifically on Lincoln and his relationship with them.

It has been this remarkable omission which motivated my research.

Lincoln’s rise coincided with the one million famine-tossed Irish flooding to America’s shores, when the population of the US was only 23 million. 150,000 Irish fought for his Union. Without them, he would almost certainly have lost.

As the war news turned against them, the Confederates mounted desperate attempts to stop the Union from recruiting in Ireland in order to try and level the battlefield. They knew how important those Irish soldiers were.

Only in the first World War did more Irish ever fight for a cause together, and yet for too long there has been silence and minimal acknowledgment. Selective amnesia has occurred not just in America but in Ireland, about the men and women (yes, there were women) from Ireland who fought in the Civil War and supported Lincoln.

The role of the 25,000 who fought for the Confederacy has to be acknowledged too, as well as the many pro-slavery Irish clerics and their flocks.

But the Irish were everywhere in Lincoln’s life, and not just as warriors. They nannied his kids, comforted his distressed wife, and Irish patriot Robert Emmet informed his political passion. He sang their songs, repeated their jokes, imitated their accents, and even came within minutes of fighting a duel with an Irish political opponent, which he later admitted was one of the lowest times of his life.

Once he got to the White House, he surrounded himself with so many Irish that there were dark rumblings in writings from other staff that he was surrounded by a Hibernian clique. Lincoln paid no attention. There was deep ambivalence in the relationship at the beginning. Lincoln was a Republican, a party that had a deep anti- Irish Catholic core because of the Know-Nothing influence. At first, this did not endear many Irish to him.

The Irish were, for obvious reasons, fighting hard against the nativists, who were intent on stopping the Irish from voting by using physical violence against them. In August 1855 during the “Bloody Monday” Louisville riots, up to 100 Irish were killed including some who were burned alive.

But Lincoln made it clear he had no truck with the Know–Nothings, and great leaders like Archbishop Hughes, General Thomas Francis Meagher, and General Michael Corcoran stood up and provided the needed leadership in their community by supporting him. Hughes ran up the Stars and Stripes over old St. Patrick’s Cathedral while Meagher and Corcoran recruited armies.

Ending slavery was never their most important task, as they saw it. It was safeguarding their own beleaguered community first, though Meagher and Corcoran spoke strongly against slavery. Meagher even called for all blacks to be allowed vote, heresy even among some Lincoln backers.

The Irish-black relationship included large numbers of intermarriages, and was generally far more complicated than has often been portrayed. Democrats played on fears of Irish-black miscegenation, which they lied was approved by Lincoln, to drive the Irish away from the president in the 1864 election.

There were also deep tensions with Lincoln’s generals, as many believed the Irish brigades were being used as cannon fodder, given their fatality rates.

Yet in the end, he plainly liked the Irish. And the Irish loved America, and resented deeply the attempt of the South to secede from it.

Unlike so many others, such as his wife and his law partner, Lincoln never spoke ill of them even in private correspondence. He had remarkably advanced views on emigration and its benefits that would shame the Know-Nothings of today.

Why is Lincoln such a fascinating topic? Perhaps because unlike Washington, to who he is most often compared, he was a man in full. Washington still feels as remote as the alabaster statue he is so often portrayed as.

Lincoln seems eternally modern; his depressions, his decidedly stormy marriage, his self-doubt, his failures, and his tragic death, coming soon after his greatest success.

But above all, there is that extraordinary vision and empathy, the ability to see what his own generals and cabinet urging compromise could not see—that the very future of democracy was on the line, that there could be no compromise on slavery. He knew that groups like the Irish were not to be despised, but brought on board in the great struggle.

He was the master mariner in waters that had never been navigated by any president, but he would need the help of the Irish and others to safely reach the shore.

Coming from a poor and underprivileged background, he understood the Irish only too well. Like him they were magnificent fighters, never better than at Gettysburg, where they played a major role in the outcome of one of the most significant battles ever.

Their story should be America’s story, but their voices only linger faintly. Their role is ignored by many contemporary historians, including Ken Burns with his landmark PBS series "The Civil War." Eminent historian Gabor S. Boritt of Gettysburg College asked a key question about the Burns series: where are the voices of the immigrant soldiers (Irish, German, etc.) who made up 25 percent of the Union Army? Where indeed.

But they were heard by Lincoln. He gave them credit and acknowledgment for what they accomplished but also held them up to criticism and punishment when they fell short, as in the abysmal draft riots, the worst moment in Irish-American history.

Ultimately, America lost its greatest president, a man who saved the fragile flower of a democracy still much less than 100 years old when the Civil War broke out. At its greatest hour of need he was there, never wavering despite lesser voices chanting for conciliation with the South and change. His absence during the Reconstruction meant unfinished business on race, which continues to this day.

At the Hampton Roads peace parley with Southern representatives in 1865, he was at his very best, demanding military surrender rather than a peace treaty that would allow wiggle room on slavery.

He was immediately adamant that slavery must go, and he kicked the underpinnings of it from underneath them forever by ridiculing the Southern leadership’s inane view that slavery was good for black folk too, as they were less intelligent.

His political skills were incredible, and his physical presence at six foot four, probably six foot seven with a stovepipe hat on, must have overwhelmed and dwarfed his opponents. His ability to relax people with his backwoods stories and an occasional Irish joke was legendary. His sense of mercy and conciliation registers far greater today, when we see so little of it practiced.

After his death, there was talk of the South rising again but it was General Robert E. Lee who put an end to that. He had come around in the end to the belief that nothing more was to be gained by restarting the murderous battle. Six hundred thirty thousand dead were more than enough.

Many were Irishmen, and Lincoln made clear in his dealings with Thomas Francis Meagher, Michael Corcoran, and Archbishop Hughes that he was indeed grateful. General Philip Sheridan had also played a huge role.

But so too had the 150,000 Irish who fought for the Union. The war was simply not winnable without them.

Lincoln stayed true to the Irish; as an utter outsider himself, that sense of the underdog likely drew him to the Irish. His own staffers complained about the “Mick Clique” around him, but he clearly reveled in the laughter and the country stories. He cared about their issues, supporting Famine relief when he was an unknown politician and ensuring their cause of Irish freedom was raised in Congress.

Lincoln’s embrace of the despised Irish should never be overlooked, nor their role in helping him win one of the most important conflicts of all times, which, with a different outcome, would have transformed the world we live in even today.

Lincoln’s greatness is never in question. Robert Lincoln O’Brien, writing in 1914 in the Boston Globe, summed up Lincoln and his meaning well:

More than a million people a year now pour into the United States from lands beyond the seas, most of them unfamiliar with our language and our customs and our aims. When we Americans who are older by a few generations go out to meet them we take, as the supreme example of what we mean by our great experiment, the life of Abraham Lincoln. And, when we are ourselves tempted in the mad complexity of our material civilization to disregard the pristine ideals of the republic, we see his gaunt figure standing before us and his outstretched arm pointing to the straighter and simpler path of righteousness. For he was a liberator of men in bondage, he was a savior of his country, he was a bright and shining light.

As for the revisionist view that he could have avoided a war, his words to Irish American judge Joe Gillespie, a close friend, shortly before he took over from Buchanan, ring true: “It is only possible upon(with) the consent of this Government to the erection of a foreign slave government out of the present Slave States.”

Lincoln was never going to allow that, but it was a close-run thing. The Irish contribution to the success has long been underplayed, even down to the present day. Many came off the Famine ships and went to war for the Union and Lincoln. Even in Union ranks they sometimes faced hostility from men like General William Sherman. But they persevered. Archbishop Hughes told them the Union and Lincoln was everything to fight for, as did their heroes. One of their own, Philip Sheridan, was the bravest general in the war. Lincoln had kissed the Irish flag and stated, “God Bless the Irish.”

So they fought. Fág an Bealach, which translates as “Clear the Way”—the old Irish war cry rings true for the American Civil War and the Irish contribution. The Irish helped enormously to “clear the way” for a deeply embattled president who ended up as America’s greatest leader. Put simply, we should never forget that the Irish helped Lincoln save democracy and end slavery; and moreover that they deserve proper recognition for their efforts.

Shares