In 1995, a person could still disappear. Stick to cash and pay phones and letters mailed with decoy postmarks, drift into a random town, lay low, blend in. In 1995, back when it took more than a few clicks to dig up anyone’s past, if a woman decided to skip town and start over, she could become whoever she wanted to be. Single. Childless. A waitress dreaming of a modest, happy life.

For a while.

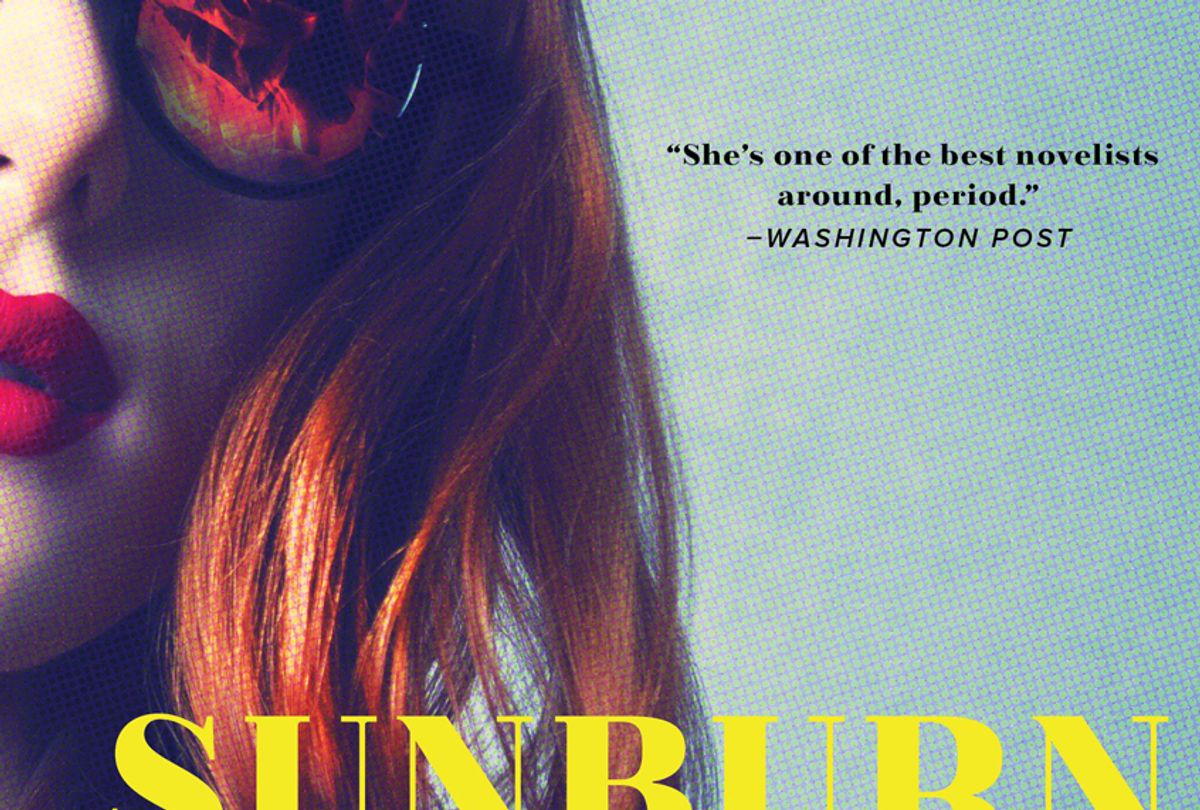

In acclaimed crime novelist Laura Lippman’s slow-burning new novel “Sunburn” (William Morrow, out Tuesday), bewitching redhead Polly Costello does just that. One day while her husband plays with their 3-year-old daughter on a beach not too far from their Baltimore home, she packs a bag, leaves two notes, and sends herself into the wind. She touches down in nearby Belleville, Delaware — with plans to move west, but not yet — a small town not close enough to the beach to be worth it, a town "put together from some other town's leftovers." In a locals tavern called the High-Ho she meets handsome Adam Bosk, also passing through but suddenly stranded in Belleville with a broken truck, the bad luck of it all, he guesses he’ll have to stay on for a while. Adam is very interested in finding out who Polly really is. They both take jobs — he's the cook, she's the waitress — and embark on what they think is a discreet affair.

And who is Polly? A woman who abandoned her child, we know from the start. And what kind of woman does such a thing? Two kinds, at least: the kind with no heart who destroys everyone in her path, and the kind with extreme self-discipline who is willing to do whatever it takes to be free. According to her husband Gregg, it’s “[t]he kind of woman he picked up in a bar four years ago precisely because she had that kind of wildcat energy.” Which kind of woman is Polly? That’s not exactly the question Adam is asking when he first approaches her in the High-Ho with his own secrets, his own capacity for drawn-out games, but it’s the only question that matters in this story.

Their affair tethers them to each other in ways neither could have predicted that first night at the bar. Then an untimely death in sleepy little Belleville tests their bond. How much do either of them really know about the other? Is their love real, or is someone getting played?

The tension in Polly’s situation increases the longer she stays put and indulges in her affair with Adam, “the first thing she’s ever chosen for her own pleasure and delight,” while her past, considerably more complex than we know at first, closes in on her. Lippman, a master storyteller, deals the story’s cards slowly and deliberately, sprinkling the book with loving homages to Maryland-native noir novelist James M. Cain's “The Postman Always Rings Twice,” “Double Indemnity” and “Mildred Pierce.”

Lippman sets Polly up with the hallmarks of the genre-standard femme fatale — mysterious, irresistible, seductive as a means to other ends, and unnaturally willing to disconnect from her child — and then delights in peeling away those traits to explore the truths behind them. Praise the fiction gods, we seem to have moved beyond the literary-world debate over whether or not female characters need to be “likeable” in fiction. The consensus, let’s hope (and if not, let’s pretend), is “who cares, as long as they are interesting.”

With Polly, an intriguing, vulnerable and insightful survivor who also walked away from her little girl, Lippman raises compelling questions about the limits of sympathy for a sympathetic woman committing an unsympathetic offense. Can you still care about a woman who would do such a thing?Are there worse things a person could do? Would you even be asking if Polly were a man? We're taught that a woman who rejects her children is unnatural. What does her disappearing act say about what else she might be capable of, and why?

Underneath it all simmers the question that keeps the pages turning, beyond the desire to find out how the pieces of Polly's past will catch up to her: Is the reader the one being played for a fool? Lippman makes it worth your while to find out.

Shares