There is no reason to think that America’s leaders will respond any differently to the latest mass shooting.

Having prayed for the latest victims of military-grade weapons, the avowed Christians in Washington will defend those weapons as liberty incarnate. Their counterparts in Florida just refused to consider a ban on assault weapons, declaring porn to be the bigger threat to public health. The NRA-approved president wants teachers to pack heat.

In other words, even modest proposals for gun control will run into the violent conviction that “real” Americans should be able to take the law into their own hands. For deep historical reasons of race and revolution, these Americans will claim the right to use deadly force, to be “sovereign” over everyone else.

It’s a long story that Americans like myself need to understand before we can overcome.

Many European monarchs dismantled the rival armies in their realms during the early modern period. Absolutists like Louis XIV also tried to stop haughty aristocrats from fighting duels. After the political union between England and Scotland in 1707, the British Crown dismantled Highland clans in the name of the law — that is, the unitary sovereignty of the state.

This is not a history of freedom. But Europeans eventually embraced the rule of law as a kind of peace treaty in which everyone gave up the power to kill in return for shared safety.

“There, perhaps, never was in government a revolution of greater importance than this,” noted a British jurist in 1758. A disarmed population was the foundation of civil society, a starting point for progress within constitutional monarchies like Britain and Denmark or republics like France and Italy.

Slave-owners held tight to their guns

The United States took a different path. In some ways this is due to the American Revolution, which was triggered in part by British efforts to disarm colonial militias. Rejecting the king set off a long debate about the source of legitimate power, resulting in a system of divided authority between the states and the central government.

But there is a darker side to this well-known story.

Many colonial slave-owners became rebels only when they decided that the British Crown threatened their “sovereign” right to dominate their labour force. After the Revolution, they clung to this individual and race-based form of sovereignty for which they were willing to sacrifice the Union in the 1860s.

Although they lost the Civil War, their ideas lived on. Klansmen took up where slave patrols left off, rejecting any rule of law that gave equal protection to Black Americans. Western vigilantes embraced violence as a citizen’s right and duty, especially in the face of Indigenous peoples or Mexicans.

This yearning for individual sovereignty sank deep into American culture, lifting the ruthless and privileged over the people at large. Under a constitutional framework where public policy is weak and divided by design, powerful individuals and interests run roughshod over society.

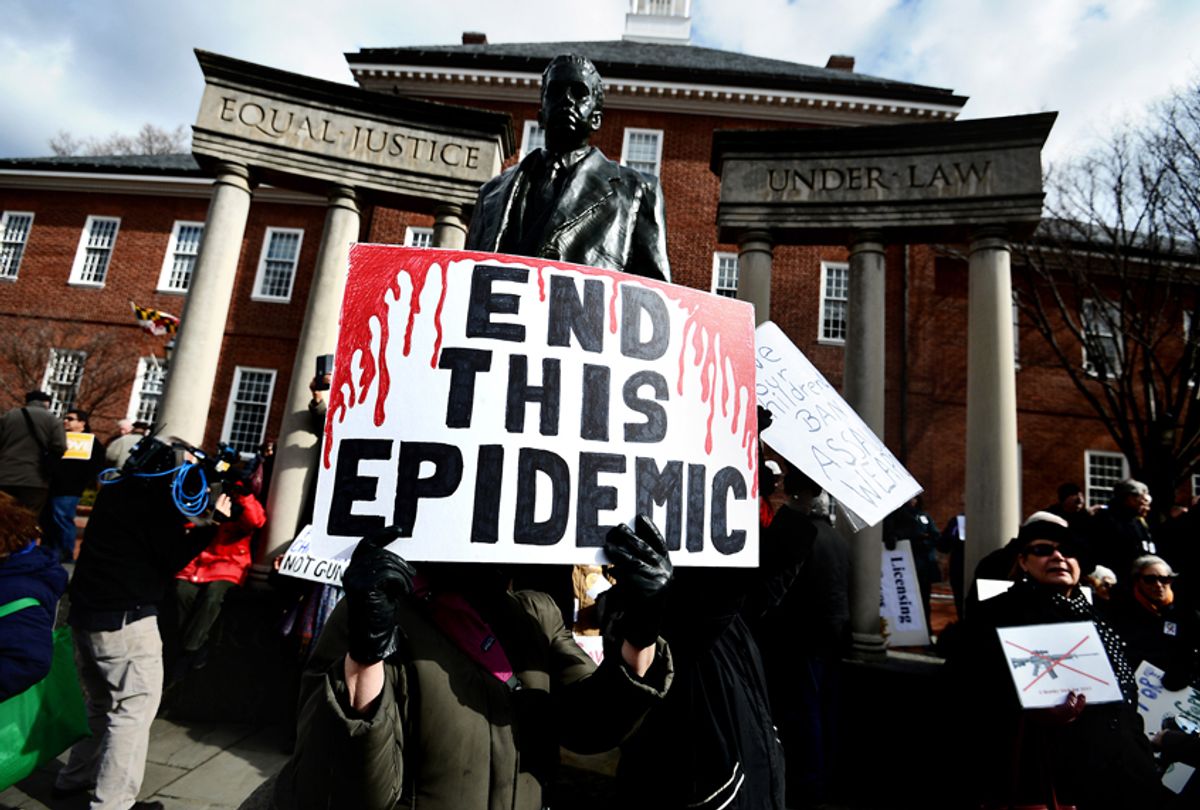

The inability to stop massacres like the one last week epitomizes this deep flaw in the American DNA. Backed by powerful gun companies, the NRA spews out a steady stream of race-tinted paranoia. Their political servants reject not only government regulation, but also the very idea of civil order, of peaceful coexistence in society. They portray the nation itself as a kind of frontier free-for-all, in which only the strong survive.

The AR-15 thus becomes “America’s Rifle.” The slaughter of innocents becomes “the price of freedom.”

In the face of this bloody madness, Americans need to think outside their political boxes. Each and every American needs to be regarded as part of a cohesive national whole, a strong society whose general welfare overrules the wild fantasies and bottomless greed of any person or industry.

Americans must confront not just bad readings of the Second Amendment but also the limitations of the Constitution itself, which is now 231 years old.

Above all, Americans must rediscover themselves as a revolutionary people who are not afraid to start over.

J.M. Opal, Associate Professor of History, McGill University

Shares