America’s political divide goes by many names — rural-urban, blue-red, metro-non-metro and left-right. We are told it is bad and that it is only getting worse, thanks to phenomena like fake news, economic uncertainty and the migration of young people away from their rural homes.

And it’s fairly common for one side of the divide to speak for the other, without knowledge of who the other really is or what they stand for. An example: The term that’s been used to describe my state’s booming economy — “Colorado’s hot streak” — is in some ways the opposite of what many rural Coloradans are experiencing. But their story rarely makes the news.

Telling someone about metro versus non-metro poverty, suicide or adult mortality rates scrapes the surface of how things are felt by those living these statistics. Descriptions never seem to do justice to how these divides are experienced, which speaks to the wisdom of the writing rule, “Show, don’t tell.”

What is that divide, really? And how can we show it?

How to communicate the divide: word clouds

I am a professor of sociology and have been studying rural and agriculture-related issues, both in the U.S. and abroad, since the late 1990s. Prior to that, I was busying growing up in rural Iowa, in the far northeast corner of the state.

A few years ago I interviewed farmers and agriculture professionals in North Dakota and members of a very different agricultural community: an urban farm cooperative. In the case of this particular urban farm cooperative, land was placed in a trust to support urban agriculture and leased to members on a sliding scale. I promised not to divulge the cooperative’s location in order to elicit participation within this group.

I wanted to know how these two communities talked and thought about issues like sustainability and food security. I was also interested in how these group members, whose lives were focused on agriculture in very different ways, illustrated some of the divides in our country.

I had a hunch these groups differed in more ways than their zip codes and socio-economic backgrounds. The North Dakota group, for instance, was all white and predominately male, whereas the urban population was considerably more diverse. The study eventually made its way into the peer-reviewed journal, Rural Sociology.

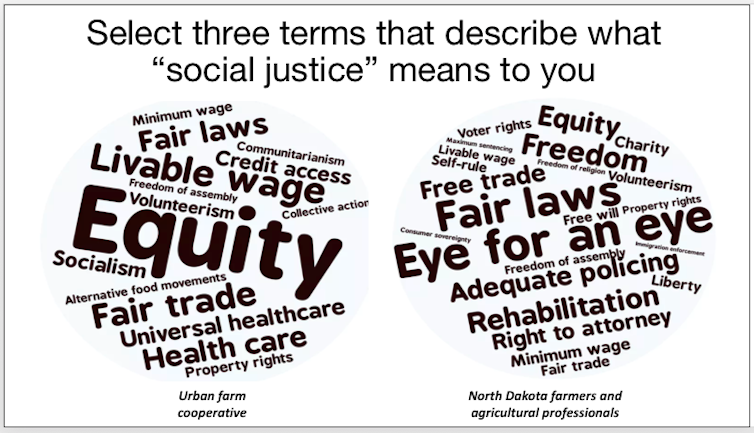

As part of the study, I built four word clouds, visual representations of words I gathered from survey questions. If a picture is worth a thousand words, these particular images show more than thousands of sentences ever could: the divergent worldviews of these two groups. And they show us an angle of the aforementioned political divide that has been missed.

Individuals in each group were asked to “select three terms that describe what ‘social justice’ means to you” and “select three terms describing what ‘autonomy’ means to you.”

Before giving their answer, participants were shown a list of some 50 terms, designed by me to relate specifically to each question. Other terms were explored as well, but only two terms — social justice and autonomy — are discussed here because they complement each other in interesting ways.

The terms respondents chose were then fed into software that generated word clouds, which are graphics that show the most-used terms in large letters, the least-used terms in smaller letters. (Disclaimer: I make no claims that these clouds speak for all Americans, farmers, North Dakotans, metro residents, etc. I also recognize that the cooperative experience could color the responses of those in the urban sample.)

Individual vs. collective

Perhaps the most immediate contrast with these social justice responses lies in how the rural North Dakotans’ image evokes a number of words associated with punishment, policing and due process, such as “eye for an eye” and “right to attorney.” These are terms associated with criminal law and the criminal justice system.

The terms chosen by the urban land cooperative, in contrast, made no reference to punishment or policing when describing their visions of social justice. Instead, they chose terms that overwhelmingly emphasized, to quote the most used term to come from this group, equity.

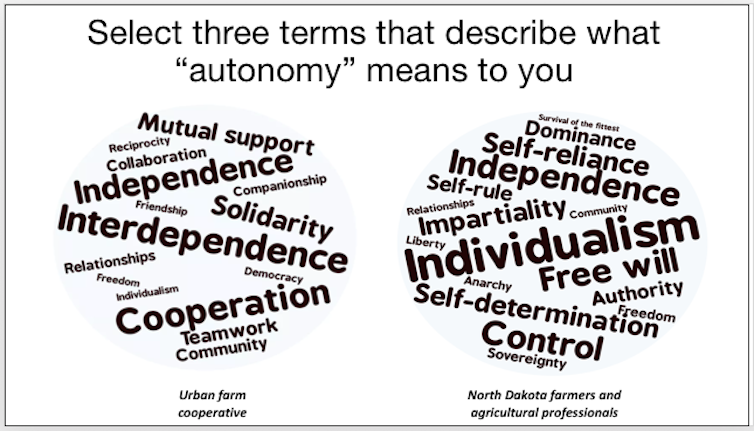

There was also a divergence between groups in terms of whether social justice was something individuals achieve or whether it denotes a collective response, where a community (or even society) as a whole ensures justice for individuals. To explain this point requires that I introduce two more word cloud images, produced in response to the autonomy question.

These autonomy word clouds demonstrate that the above contrasts are no fluke and are important for two reasons. First, they validate that there is something “deeper” afoot. And second, they inform the social justice images.

Note the repeated emphasis the North Dakota group placed on terms like “individualism,” “self-determination,” “self-rule” and “authority.” In philosophical parlance, these terms align with the tradition of individualism, a position that emphasizes self-reliance and that stresses human independence and liberty.

These terms also tie in well with the North Dakota group’s social justice word cloud, with its emphasis on words that emphasize individual responsibility, e.g., “eye for an eye,” and individual freedoms, “fair laws” and “right to attorney.”

This stands a world away from the urban farmer cooperative group, who associated autonomy with “interdependence,” “cooperation,” “solidarity” and “community.” It might appear counterintuitive to link autonomy with concepts like interdependence and solidarity, until you hear individuals from this group explain their position.

A single mother, for example, spoke directly to how independence arises for members of this group because of interdependence, rather than in spite of it.

“We can accomplish a heck of a lot more together; I feel like I have more control over my life, more independence, when we can rely on each other.” She added, “I certainly appreciate how sharing childcare opportunities as a community gives me the freedom to garden. But we can’t forget that farming has always been a collective effort, of sharing seed and knowledge and work.”

The cooperative group’s views of social justice focused significantly on community outcomes and injustices as opposed to purely individual ones. This point about the urban group expressing something resembling a collectivist understanding of social justice came out especially clear in the qualitative interviews with members of the cooperative.

Among the members’ statements was one given by a man while he was erecting tomato cages with his two brothers, uncle and another man who 12 months prior was living in his home country of Costa Rica. Asked what social justice meant to him, he said, “Justice isn’t about charity; it’s about community empowerment; not about what you’re given but about intentionally realizing your aspirations collectively.”

Disagreements can lead to dialogue

The above images reflect disagreements, to be sure, and contextualize our inability to find common ground on such issues as climate change, guns and the social safety net. If one starts from the premise that an individual can only make good, right and just decisions when they’re left alone, then their position on those hot button issues will look a lot different from those who think individual freedom is enhanced when those liberties are balanced out by constraints determined by ideas about the collective good. In short, consensus is a stretch when one “side” preaches self-reliance and self-rule while the other speaks of “independence” and needing to “rely on each other” in the same sentence, as the mother from the cooperative did.

So what does this study of these two groups and their ideas mean? Does bridging the political divide in the U.S. mean groups like this need to settle all of their political disputes and arrive at consensus about everything?

Of course not. Disagreements are good when they encourage dialogue and debate.

What we have now in our country appears to sometimes border on combativeness if not outright hate, which has me deeply concerned, both as a sociologist and a citizen.

Before we can hope to repair the divides (plural, since these differences clearly go beyond rural-urban) we need to first understand how deep they cut. You wouldn’t prescribe a Band-Aid for a gash that requires stitches. The following are three concluding thoughts as we triage this wound.

Replace caricatures with actual encounters

First, the opposing worldviews illustrated in the word clouds have less to do with each group having different levels of knowledge and more to do with processing knowledge through very different filters. Thus, settling political disputes by arguing over “the facts” is futile, at least in some instances.

Second, a few respondents from each group appeared to be straddling “worlds.” People like this can be very helpful in bridging our political divides. Instead of building alliances based on geopolitical identities (e.g., ethnicity, political affiliation, rural/urban), we might explore how this process could start by engaging those who, like these few respondents, share similar worldviews.

Third, these worlds risk growing further apart the more their respective inhabitants look inward. The alternative would involve creating situations where we can get to know some of the people and livelihoods that are a world away from what we otherwise experience. That means the caricatures of rural and urban America need to be replaced with actual encounters.

Whoever thinks fences make for good neighbors has been infected by today’s political climate. What we need are bridges. It is time we start building them — and walking across the political divide.

Michael Carolan, Professor of Sociology and Associate Dean for Research & Graduate Affairs, College of Liberal Arts, Colorado State University

Shares