Apple is a business. And we’ve somehow attached this emotion [of love, devotion, and a sense of higher purpose] to a business which is just there to make money for its shareholders. That’s all it is, nothing more. Creating that association is probably one of Steve’s greatest accomplishments.

—Andy Grignon, iPhone senior manager, 2005–2007

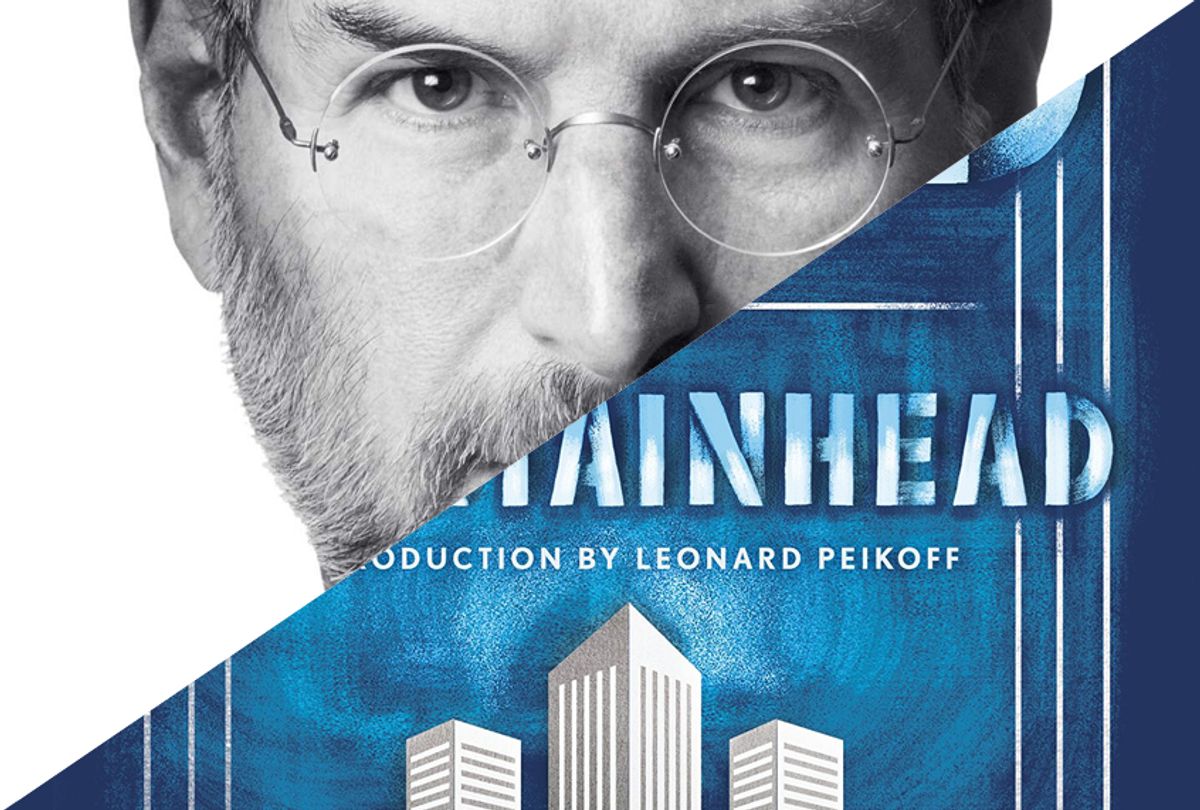

You’d be hard-pressed to find a tech entrepreneur who does not identify with the portrait of Steve Jobs as depicted in Walter Isaacson's eponymous book. Seven years after its release, the authorized biography of the Apple co-founder has lost none of its power to beguile. Arguably, Isaacson's book is the most influential guide to high-functioning malice since “The Fountainhead.” It's a story that tech visionaries read, and learn nothing from.

"Walter Isaacson’s biography Steve Jobs didn’t just create a Hollywood hit,” wrote Krister Ungerboeck in Quartz, “it created a manual for any bosses seeking a hall pass for their temper tantrums.”

In 2015, director Danny Boyle and screenwriter Aaron Sorkin released a monster movie based on Isaacson's biography, featuring the highly likable and definitely human Michael Fassbender. This added to the mythos and glamor of the man and ensured that Isaacson’s book would be handed out to business school grads for the next thousand years.

It’s as easy to detect dysfunctional behavior in the book as it is to find atoms in a jar of bourbon. You could spin out a full feature numbering the times Jobs parked in handicapped spots. But one moment will stand for the whole — the time when Atari paid Jobs and Steve Wozniak a $5000 fee for designing a piece of hardware. According to Isaacson, Jobs gave Woz $350 of the amount, and pocketed the rest:

Astonishingly, they were able to get the job [for Atari] done in four days, and Wozniak used only forty-five chips. Recollections differ, but by most accounts Jobs simply gave Wozniak half of the base fee and not the bonus Bushnell paid for saving five chips. It would be another ten years before Wozniak discovered (by being shown the tale in a book on the history of Atari titled Zap) that Jobs had been paid this bonus. “I think that Steve needed the money, and he just didn’t tell me the truth,” Wozniak later said. When he talks about it now, there are long pauses, and he admits that it causes him pain. “I wish he had just been honest. If he had told me he needed the money, he should have known I would have just given it to him. He was a friend. You help your friends.”

Certain people play the villain in their youth. We ought to have charity for them: there are parts of the brain that don't activate until mid- to late-twenties. But Jobs stayed in character his entire life. In 2010, a year before he died:

The meeting [between Jobs and Obama] actually lasted forty-five minutes, and Jobs did not hold back. “You’re headed for a one-term presidency,” Jobs told Obama at the outset. To prevent that, he said, the administration needed to be a lot more business-friendly. He described how easy it was to build a factory in China, and said that it was almost impossible to do so these days in America, largely because of regulations and unnecessary costs.

The house that Steve built

If you want to see Jobs' real legacy in the Valley, you won’t need to search for long. He's around every corner, as inevitable as a Facebook vaccination scare. Every time a Stanford dropout with ten pounds of vision and two pounds of planning types out a press release, Jobs is there. Beat the bushes with a slender reed and out jumps his name. Take Jack Dorsey, who runs the internet's most reliable haven for white supremacists, Twitter:

Jack Dorsey says he takes a lot of inspiration for what he does from late Apple founder Steve Jobs. When he designs products, whether at Twitter or Square, Dorsey said he aims to create products that disappear so you are just using them. Calling Jobs “a mentor from afar,” Dorsey said Jobs has had a major impact on his approach to business.

In Alexander Mallery's "Searching for Steve Jobs," Elizabeth Holmes, now-infamous founder of the disgraced and bankrupt Theranos, is described as follows:

The physical image that Holmes cultivated is the clearest source of possible comparisons. According to his biographer, Walter Isaacson, Steve Jobs’ “signature style” (Isaacson, 2011) was the black turtleneck, which Holmes appropriated—along with “black slacks with a wide, pale pinstripe; and black low-heel shoes” (Parloff, 2014). Her hair was, without fail, “[pinned] into an unruly bun” (Parloff, 2014). Holmes even had a snippet of Jobs’ Apple biography hanging above her desk (Parloff, 2014).

As Mallery explains, "The cult of personality that [Holmes] created — and the comparisons she evoked to the late Steve Jobs—are what gave Theranos its power in the public eye." According to Mallery, "the Theranos fraud" was made possible "not by any ordinary technological hype" but because Theranos told the world that Holmes was just like Jobs, thereby ensuring their success would match. "The comparison between Holmes and Jobs," Mallery noted, "was already so strong that Holmes’ veil of secrecy seemed perfectly acceptable, completely unsurprising, to those outside the healthcare industry. It had worked before; why, for such a similar person, shouldn’t it work again?"

But what is Holmes' minor success at sleight-of-hand, when compared to Uber-bro Travis Kalanick's epic multi-level redemption campaign? As Sarah Lacy wrote in an article in PandoDaily, “Travis Kalanick isn’t ‘Steve Jobs-ing’ anything”:

Walter Isaacson’s book about Steve Jobs features a scene where’s Jobs is so angry to have been ousted from Apple that he stares out his widow listening to “The Times They Are a Changin’” on vinyl over and over again. “The loser now will be later to win…” Travis Kalanick seems to have internalized this part of the Jobs narrative….and only this part. According to Re/Code, Kalanick has been telling friends he’s planning to “Steve Jobs it” and return as CEO of Uber.

Even Evan Spiegel of Snapchat is an adherent of the Book of Jobs:

When asked about Spiegel’s controlling tendencies, his supporters like to point to Steve Jobs, who was not known for running Apple as a democracy. If it worked for Jobs, why can’t it work for Spiegel? Not a coincidence: Spiegel has a painting of Jobs hanging in his office.

In defense of Isaacson

The shadow of “Steve Jobs” is not Isaacson's fault. The author is blameless as a corn harvest sacrifice. He did not whittle the cult of Jobs out of pine wood — he's just the last link in a very long, golden chain. The ballad of the turtlenecked messiah was built brick by brick, profile by profile, spin by spin, over five decades. The fact that Isaacson is the capstone on a sealed, off-white pyramid does not make him a collaborator. Isaacson kept the faith with his audience: the biography itself is thorough, informative and fair-minded throughout. Which is remarkable, considering that the book was authorized, and given Jobs' obvious powers of seduction. If an incredibly powerful billionaire asked you to write his biography, could you do it without descending into hagiography?

If Isaacson himself is innocent, and if the book is balanced, what explains “Steve Jobs'” strange, Randian halo effect?

I suggest “Steve Jobs” is the beneficiary of a strange set of circumstances. Most religious founders write nothing themselves: their words and deeds are collected only after their passing. In the case of Isaacson's book, the biography was published nineteen days after Jobs' death. What made “Steve Jobs” the focal point for the postmortem cult of Jobs was simple: it took all of the inchoate yearnings and illustrative anecdotes and free-floating admiration for Jobs and wrapped it up together in a single tome, a holy text. A teaching tool for any entrepreneur who dreamed of being successful enough to shout at their employees. The book codified and made explicit the hypothesis of Steve Jobs.

The Jobs Defense is the tech equivalent of Stephen King's Theory of Alcoholic Writers:

Alcoholics build defenses like the Dutch build dikes. I spent the first twelve years or so of my married life assuring myself that I “just liked to drink.” I also employed the world-famous Hemingway Defense. Although never clearly articulated (it would not be manly to do so), the Hemingway Defense goes something like this: as a writer, I am a very sensitive fellow, but I am also a man, and real men don’t give in to their sensitivities. Only sissy-men do that. Therefore I drink. How else can I face the existential horror of it all and continue to work? Besides, come on, I can handle it. A real man always can.

Like the Hemingway Defense, the Jobs Defense is similarly tautological: I am a founder, therefore I am like Jobs, therefore I must be cruel like Jobs. How else can I be a successful founder?

This defense is shared by a lot of "gifted" people. But there's no evidence for this claim, that cruelty equals success. Isaacson says so, several times in this book: "The nasty edge to his personality was not necessary."

Who's got their claws in you, my friend?

According to management professor Brad Gilbreath, a worker's rapport with their manager is a leading predictor for psychiatric damage in the workplace. As Willow Lawson pointed out in Psychology Today, "Gilbreath found that a worker's relationship with his boss is nearly equal in importance to his relationship with his spouse when it comes to overall well-being."

The Alliance Manchester Business School did a study of 1,200 people in different countries and professions. As Amanda MacMillan wrote of the study, people forced to work for bosses with "dark traits" resulted in workers having higher depression rates, lower job satisfaction and counterproductive behavior — including workplace bullying:

The new research found that people whose bosses display psychopathic and narcissistic traits not only feel more depressed, but they are also more likely to engage in undesirable behaviors at work—like being unproductive and acting rude themselves. The findings, which have not yet been published in a peer-reviewed journal, were presented today at the British Psychology Association’s annual conference for occupational psychology in Liverpool.

Jack Zenger and Joseph Folkman, writing for the Harvard Business Review, pointed out good leaders have a "straight-line correlation" with staff engagement. A study of 2,865 leaders showed that

. . . the satisfaction, engagement, and commitment levels of employees toiling under the worst leaders (those at or below the 10th percentile) reached only the 4th percentile. (That means 96% of the company’s employees were more committed than those mumbling, grumbling, unhappy souls.) At the other end, the best leaders (those in the 90th percentile) were supervising the happiest, most engaged, most committed employees — those happier than more than 92% of their colleagues.

As Tom McNichol wrote in the Atlantic after Isaacson's book came out, jerk logic tends to ignore any facts that disprove its thesis:

This distorted reasoning was already prevalent before Steve Jobs's death, and is only likely to spread as Isaacson's biography closes in on becoming the best-selling book of 2011. Five years ago, when Stanford professor of management science and engineering Robert Sutton was researching his book, “The No Asshole Rule: Building a Civilized Workplace and Surviving One That Isn't,” he ran across a disconcerting number of Silicon Valley leaders who believed that Steve Jobs was living proof that being an asshole boss was integral to building a great company. Sutton's counter-thesis was that assholes — which he defined as those who deliberately make co-workers feel bad about themselves and who focus their hostility on the less powerful — poison the workplace and induce qualified employees to quit and are therefore bad for business, regardless of the asshole's individual talent or effectiveness.

Rethinking Jobs’ legacy

During Jobs' life and after his death, his "cruelty, arrogance, mercurial temper, bullying and other childish behaviour were well-known," as Sue Halpern writes in Financial Review. Jobs (and Apple's) history of borrowing other people's ideas was widely-known. Cupertino's tax-dodging schemes and the harmful working conditions of Apple's laborers in China — and the resulting suicides — had been made public. Why then, asked Halpern, did anyone outside of his family feel any attachment to this man?

Why didn't people sob in the streets when George Eastman or Thomas Edison or Alexander Graham Bell died – especially since these men, unlike Jobs, actually invented the cameras, electric lights and telephones that became the ubiquitous and essential artifacts of modern life? The difference, suggests the MIT sociologist Sherry Turkle, is that people's feelings about Jobs had less to do with the man and less to do with the products themselves, but everything to do with the relationship between those products and their owners, a relationship so immediate and elemental that it elided the boundaries between them. "Jobs was making the computer an extension of yourself," Turkle tells Gibney. "It wasn't just for you, it was you."

What consumer goods are to ordinary people, Isaacson's book is to executives and bosses: an extension of themselves. The ultimate product is Jobs himself: the CEO you could be, if you didn't have human decency to hold you back.

Why are Jobs' failings of character worth talking about? Because so much executive behavior, especially within Silicon Valley, is a deliberate echo of his malfunction. Jobs' nature matters for the same reason Jefferson's hypocrisy matters. Our systems are based on poorly-designed hardware. If faced with brokenness, we are obliged to hack the system and fix the parts, using democratic means and ideals. Crowd-sourcing the future, in other words. Jobs would have hated that. But those are the terms and conditions of doing what John Sculley tried to do in 1985: oust Jobs for good.

Shares