Having grown to dominate book-selling, cloud computing, taking a huge chunk of online retail, and starting the home assistant market, Amazon appears to be angling to get into the banking business next.

The exploration, which was first reported by the Wall Street Journal, follows the company's efforts to start up its own shipping company and its 2017 purchase of the grocery store company Whole Foods. The finance effort is said to focus on enticing people who do not currently use banking services.

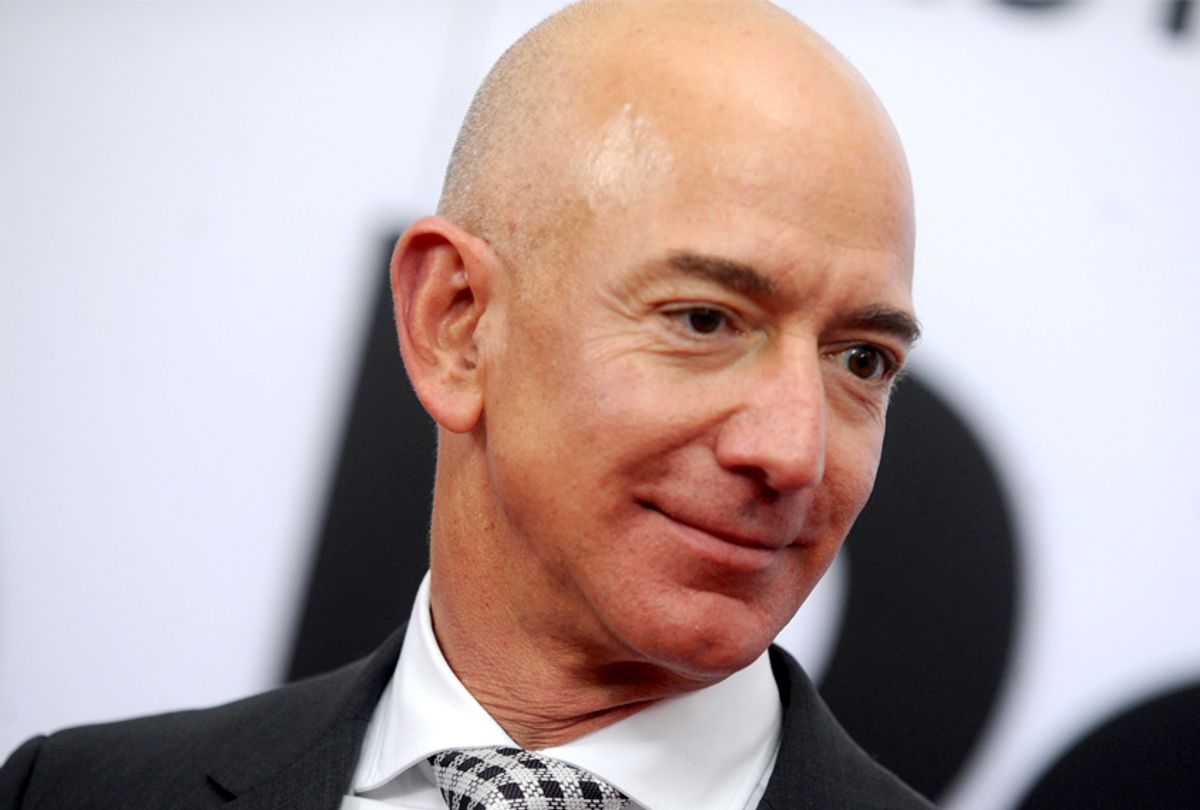

Amazon's seemingly insatiable appetite for growth and cost-cutting has raised concerns among consumer advocates and among companies and workers in the fields that it dominates; but should the Jeff Bezos-led giant decide to work to disrupt the banking industry, consumers might prefer them to Wall Street.

In a poll conducted last July for Bloomberg News, just 31 percent of respondents said that they had a favorable perception of Wall Street banks.

Frustrated with high overdraft fees, minimum balance fees, and other consumer-unfriendly policies common in the industry, about 7 percent of American households don't use a bank at all, according to research on "unbanked" people by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. Some 20 percent of Americans are "underbanked" according to the report — meaning that they use banks for things like checking accounts, but also utilize other methods of obtaining financial services.

According to the FDIC, a majority of "unbanked" households say they cannot afford to keep enough money in an account to avoid overdraft fees.

While Amazon may be able to provide lower-cost banking services to such people, it may also encourage more impulse buying by leveraging information gleaned on consumer spending to better target them for advertising or by steering them to purchase products made by Amazon instead of competitors. This scenario is not hypothetical, either. Right now, Amazon's Alexa voice assistant will not order products that are sold by vendors who do not participate in its Prime program.

While Americans generally value low prices over privacy concerns or supporting small businesses, there may be a limit to how much Amazon can expand into other sectors before encountering massive resistance. Without governmental oversight, it's become rather clear — as Stacy Mitchell, co-director of the Institute for Local Self-Reliance, noted in an article for The Nation last month — that Amazon simply will not stop until it has become the global infrastructure company. As Mitchell wrote:

Bezos has designed his company for a far more radical goal than merely dominating markets; he’s built Amazon to replace them. His vision is for Amazon to become the underlying infrastructure that commerce runs on. Already, Amazon’s website is the dominant platform for online retail sales, attracting half of all online US shopping traffic and hosting thousands of third-party sellers. Its Amazon Web Services division provides 34 percent of the world’s cloud-computing capacity, handling the data of a long list of entities, from Netflix to Nordstrom, Comcast to Condé Nast to the CIA. Now, in a challenge to UPS and FedEx, Amazon is building out a vast shipping and delivery operation with the aim of handling both its own packages and those of other companies.

By controlling these essential pieces of infrastructure, Amazon can privilege its own products and services as they move through these pipelines, siphoning off the most lucrative currents of consumer demand for itself. And it can set the terms by which other companies have access to these pipelines, while also levying, through the fees it charges, a tax on their trade. In other words, it’s moving us away from a democratic political economy, in which commerce takes place in open markets governed by public rules, and toward a future in which the exchange of goods occurs in a private arena governed by Amazon. It’s a setup that inevitably transfers wealth to the few—and with it, the power over such crucial questions as which books and ideas get published and promoted, who may ply a trade and on what terms, and whether given communities will succeed or fail.

Shares