Read the first half of this history of the Free South Africa Movement.

Starting in 1977, the antiapartheid movement briefly became a strong contender for more public attention and for interest not just locally but also in the administration and Congress because of regional developments in Africa. In 1976, Portugal left Africa, stripping and taking off with whatever they could. South African officials continued to use armed insurgencies against the new, rising internal independence movement and independent neighboring countries that had joined forces to overthrow the apartheid regime.

President Carter appointed people who had experience and interest in Africa. Goler Butcher, who had served as Diggs’s counsel on the Subcommittee on Africa, became Africa bureau chief in the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). Andrew Young, a Georgian, who was rewarded for his early support of Carter with the UN ambassador post, said the civil rights movement had put them in good position to attack apartheid, since it was essentially a civil rights issue. They had to fight off National Security Council chief Zbigniew Brzezinski, who linked Ethiopia and Angola to Cuba and the Soviet Union, still advancing the Kissinger East versus West priority, an anticommunist framing of the African situation.

None of this activity seemed to make a dent in changing U.S. policy or the apartheid regime. Further, the bright prospects for change quickly evaporated. Charlie Diggs left because of corruption charges in early 1979, and Carter fired Andrew Young for violating the no talk-with-the-Palestinians policy. Stephen Solarz (D-NY) became chair of the House Subcommittee on Africa, and Howard Wolpe (D-MI) took the post in 1981. Despite Reagan’s election and Republicans gaining control of the Senate, the House Subcommittee on Africa tried to move forward. The new chair and staff kept up study missions to countries in southern Africa and Namibia and held serious hearings. As members of Congress from the Black Caucus and others interested in Africa grew in numbers and seniority, additional committees began to investigate matters such as U.S. financial dealings with South Africa.

After TransAfrica was founded in 1977, it joined with ACOA, the Washington Committee on Africa (WCOA), the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC), and other groups to educate the public andto advocate for socially responsible investment. Harry Belafonte and Arthur Ashe formed Artists and Athletes Against Apartheid to ask entertainers to stop working in South Africa and the Sun City resort for white South Africans. Randall Robinson of TransAfrica testified before congressional committees, wrote letters to politicians, and was increasingly frustrated because there was too little public interest in changing American policy toward Africa. He concluded that the media showed political interest when something happened that threatened places with a significant number of whites. The obvious answer was that the precarious future of whites in South Africa, Namibia, and Rhodesia made those places the best possible sites to redirect policy.

In May 1981, an anonymous government employee informant, whom Randall did not know, gave him classified papers about Secretary of State Alexander Haig’s meeting with South African foreign minister Roelof Botha on furthering the United States’ “constructive engagement policy,” a label coined by Chester Crocker, assistant secretary of state for African affairs, to relieve South Africa’s “polecat” status in the world. Randall gave the papers to the press, which led to stories in the Washington Post and other media outlets, and he also went to an Organization of African Unity meeting and distributed copies of the secret papers to representatives of the African countries.

Zimbabwe gained its independence in 1980, joining with an independent Angola, even though its South African-fueled military conflict continued. Namibia, however, was still under the control of South Africa, and black Namibians and black South Africans still suffered under apartheid. Blacks in South Africa grew increasingly restive and repressed. In 1982, AFSC published a citizen’s guide for local people on how to withdraw funds from banks and corporations involved with South Africa. Antiapartheid protesters joined in a June 1983 national antinuclear march and the August 1983 March on Washington. The Dennis Brutus asylum campaign was another avenue for protests. In the fall of 1983, Randall suggested civil disobedience, but congressional staffers thought it was too soon. In October 1983, 300 attendees at a national students’ conference in New York planned demonstrations against apartheid for March and April 1984.

In September 1984 came the parliamentary change in South Africa that gave the franchise to coloreds and Indians but not blacks. Protests and repression grew and U.S. constructive engagement continued. Then, in October 1984, the United States, guided by Ronald Reagan, abstained from a United Nations General Assembly resolution condemning protests against the continued suffrage policy restriction. The assembly had repeatedly denounced apartheid as racism since 1962. Apartheid also had been an issue in Jesse Jackson’s 1984 presidential campaign.

Richard Hatcher, chair of TransAfrica’s board, felt that the organization needed to protest the White House since Reagan’s reelection in 1984 ensured continued American complicity with apartheid. Hatcher was the first black elected mayor of a large city (Gary, Indiana), in 1968, and chair of Jackson’s presidential campaign. Sylvia Hill and the other SASP members and TransAfrica decided to engage in a nonviolent protest at the embassy, the official symbol of South Africa in the United States.

There had been other protests against South Africa in the United States before FSAM. None had dented apartheid. But this history provided the context for the FSAM campaign. When TransAfrica announced the Free South Africa movement, we initially thought the protests might go on for a week. TransAfrica lined up prominent people who, if the first day was successful, had agreed to be arrested: Congressman Charles Hayes (D-IL) and the Reverend Joseph Lowery, chair of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference on the 26th of November; Congressman John Conyers (D-MI) and William Simons, president of the Washington Teachers Union, on the 27th; Congressman Ronald Dellums (D-CA), Marc Stepp, UAW vice president, and Hilda Mason, D.C. Council, on the 28th; Yolanda King, daughter of Martin Luther King Jr., Gerald McEntee, president of AFSCME, and Richard Hatcher, mayor of Gary, Indiana, on the 29th; Congressman George Crockett (D-MI), Congressman Don Edwards (D-CA), and Leonard Ball, Coalition of Black Trade Unions, on the 30th.

Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Roger Wilkins, former assistant attorney at the Justice Department and nephew of the NAACP’s Roy Wilkins, and Bill Lucy, AFSCME secretary-treasurer and president of the Coalition of Black Trade Unionists, joined the FSAM steering committee in the first week. Randall, Walter, Bill, Roger, and Sylvia Hill, founding members of the Southern Africa Support Project, and Cecelie Counts, as both a founding member and coordinator for FSAM, met early every morning at my house to plan our activities. At first, Randall and his staff may have seen Congressman Walter Fauntroy and me mainly as celebrities who could attract the media spotlight, but with our first meetings, it became clear that our committee collectively had the experience to sustain a movement and make mostly good decisions.

Unlike those students who started the anti-Vietnam War protests 20 years earlier, the original FSAM steering committee members had a great deal of activist experience and knowledge of civil disobedience and of Africa, which informed decisions during the movement. Also, we had experience in government and dealing with government to help us understand how to move legislation. Randall Robinson had spent time in Tanzania in the fall of 1970, which, after Nkrumah fell in Ghana, was the most welcoming African country for black Americans. He and fellow Harvard law students Henry and Rosemary Sanders had trouble getting funded for research fellowships in Africa after law school. They went to the black assistant dean Walter Leonard, who got the Ford Foundation to create a Middle East and Africa Field ResearchProgram for Afro-Americans. The Sanderses went to Nigeria; Robinson went to Tanzania.

Randall, back in Boston in the winter of 1971, worked in a legal assistance office for three years, then at the Roxbury Multi-Service Center as a community organizer. He was an organizer of a protest asking for a Gulf Oil boycott and demanding Harvard’s divestment of Gulf Oil stock because of the company’s key support of colonialist regimes in Africa. Harvard held the largest block of Gulf stock of any American university. In Angola, the oil the company pumped provided 48 percent of Angola’s budget. The protests included a graveyard of one thousand black crosses, which were built on the Harvard campus, and the takeover on April 21, 1972, of the administration building. Harvard didn’t relent, but the educational value was enormous.

Then Robinson went to work for Congressman Charles Diggs, chair of the House of Representatives’ Africa Subcommittee. Before Diggs was felled by a corruption scandal dating to before Randall’s time, every black American who wanted to do policy work on Africa came into his orbit. By the late fall of 1976, Portugal had retreated from Africa and Rhodesia’s government was on the run. Randall went to Cape Town in December 1976 as part of a congressional delegation chaired by Diggs, who offended South Africans by asking when blacks would get the right to vote.

During the Congressional Black Caucus weekend in 1976, the NAACP, black church labor unions, Greek letter organizations, the National Council of Negro Women, and business leaders met with Herschelle Challenor, counsel to the House Africa Subcommittee. These organizations and leaders decided to form TransAfrica, which was incorporated July 1, 1977, as an organization of black Americans to influence US foreign policy on Africa and the Caribbean. Randall became executive director. Because funding was always shaky, the organization started with a fund-raiser, led by his brother Max Robinson, a leading TV newscaster.

Walter Fauntroy was a student at Virginia Union University when he met Martin Luther King Jr. Fellow Baptist ministers, they became friends. Fauntroy joined the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and upon his return to his hometown, Washington, DC, he became a congressional lobbyist for civil rights. Fauntroy also helped to coordinate the 1963 March on Washington and became pastor of New Bethel Baptist Church and director of the Washington bureau of the SCLC. He served as DC coordinator of the 1963 march, the Selma-to-Montgomery march, and James Meredith’s 1966 Mississippi “March Against Fear.” President Lyndon Johnson appointed Fauntroy vice chair of the White House Conference on Civil Rights in 1966 and vice chair of the DC Council in 1967. He founded and headed the Model Cities organization in DC and tried to stop the violence when riots overcame parts of DC after King was assassinated in 1968. Fauntroy served on the city council and then became the district’s first nonvoting delegate to Congress in 1971. Based on his local prominence, experience as a civil rights activist, and service in Congress, Walter was a good choice to become one of the first FSAM protesters.

I was a member of the U.S. Civil Rights Commission and had a great deal of very recent and extensive national press coverage because of fighting Reagan’s attempt to turn back the clock on civil rights. Reagan had fired me for opposing him, but I sued him and won reinstatement in a federal court suit. I also had a great deal of nonviolent protest experience. Between graduate school and law school at the University of Michigan, I had gone to Vietnam to report on the war. I had been involved in anti-Vietnam War protests on campus. And I had been one of the students who took over the university president’s office on April 9, 1968, the day of Martin Luther King Jr.’s burial in Atlanta, to demand more funding for African American students and African American faculty hires.

In 1970, I was a new faculty member at the University of Maryland, College Park, when an antiwar protest that was bigger and possibly more raucous than the one at Kent State erupted. Thousands of demonstrators occupied and vandalized the university’s main administration building and ROTC offices, set fires all over the campus, and blocked Route 1, the main artery into College Park. Armed with bricks, rocks, and bottles, the protesters continuously skirmished with police, who were armed with riot batons, tear gas, and dogs. As the campus raged, Maryland governor Marvin Mandel finally sent in National Guard troops in an effort to quash the uprising.

Fortunately, unlike Kent State, no lives were lost at College Park. The chancellor asked me and a few other faculty members to sit with him and advise him. I had also gone back to Central Michigan University to help talk the students into ending an armory protest after Kent State, when the university president did not want to let the governor send in the National Guard to arrest protesters because his daughter was one of the protesters.

Also, when I was chancellor at the University of Colorado, Boulder, I went outside to meet with students who thought they had to take over a building to get my attention on an issue of academic policy. So, I had lots of nonviolent civil disobedience experience and from both sides.

I also had experience with the African liberation struggle. I had participated in the sixth Pan-African Conference in Tanzania in the summer of 1974, where African heads of state and other speakers argued over Marxist-Leninist reforms as opposed to capitalistic measures against black oppression. Some black nationalists agreed that a socialist revolution might be necessary, but they didn’t think the racism of white workers could be overcome and felt blacks could be liberated only by their own efforts. During the Carter administration, I had also visited South Africa. At that time, I met in the country secretly with some of the freedom fighters. While at the University of Maryland, I had also become acquainted with Zimbabweans and had visited some of the guerrillas in Zambia before independence. When independence came, as a Carter administration political official, I took the opportunity to talk with Zimbabwean president Robert Mugabe at the White House on his first visit to the United States. I went again to Zimbabwe and observed whites screaming loudly, objecting when traffic stopped for the motorcade of the new president, calling him a “monkey.”

Eleanor Holmes Norton was an experienced civil rights activist. While in college and graduate school, she was active in the civil rights movement and an organizer for SNCC. By the time she graduated from Antioch College, she had already been arrested for organizing and participating in sit-ins in Maryland, Ohio, and Washington, DC. While in law school, she traveled to Mississippi for the Mississippi Freedom Summer and worked with civil rights stalwarts like Medgar Evers. Her first encounter with a recently released but physically beaten Fannie Lou Hamer forced her to bear witness to the intensity of violence and Jim Crow repression in the South. Upon graduation from law school, she clerked for Judge A. Leon Higginbotham. She was a litigator at the ACLU, head of the Human Rights Commission of New York City, and head of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, named by Carter. She then was a professor at Georgetown and a member of FSAM.

A key activist who was not in the room at the meeting with the ambassador when we started the protest, because she was not as obviously newsworthy at the moment, was an academic, Professor Sylvia Hill of the University of the District of Columbia. She had been a leader working for the liberation of southern Africa since the 1970s. She had been the North America regional secretary general for the Sixth Pan-African Congress, held in Tanzania, which I attended. At that time, she was a professor at Macalester in St. Paul, Minnesota, and some of her students helped with the conference and the movement. She and her husband, James, had been in SNCC in Mississippi and moved to Minnesota, which was his home. After SixPac, they moved to Washington, DC, bent on organizing to help the liberation of southern Africa. She and Joseph Jordan, Sandra Hill, Cecelie Counts, Adwoa Dunn-Mouton, and others founded the Southern Africa Support Project (SASP), which did a study of local churches and other organizations to find out which ones were most likely targets for organizing. They gave presentations and formed a network of local volunteers interested in the liberation cause. In 1980, Sylvia persuaded ANC head Oliver Tambo, who visited with SASP while in Washington, that Americans could be as responsive to the antiapartheid movement as Europeans, who were its major supporters. Tambo began to allocate resources in the United States. Thereafter, Lindiwe Mabuza, who was assigned to Washington, DC, and Johnny Makatini, serving at the United Nations, gave our movement knowledge and a sense of the ANC’s visions and goals. They traveled, met, and talked with people and collaborated with antiapartheid, traditional civil rights, and women’s groups and appeared in the media wherever they traveled. Adwoa Dunn-Mouton, a SASP member, was the group’s most important black staffer on the Hill serving on the Subcommittee on Africa. SASP organized and delivered the core daily demonstrators, drummers, and picketers when the movement started and as it continued in Washington.

In massive resistance to apartheid, black South Africans mobilized to make the townships ungovernable, black local officials resigned in droves, and the government declared a state of emergency in 1985 and used thousands of troops to quell “unrest.” That, and the success of FSAM and antiapartheid protests around the United States, brought routine media coverage to the South African issue, and congressional action on sanctions became possible. Randall and his staff met weekly with members of Congress, usually in Senator Edward Kennedy’s office.

The antiapartheid public mood became so strong a month after the FSAM embassy protests started that in December 1984, twenty-five conservative Republican House members wrote an open letter to Prime Minister Botha threatening sanctions if apartheid continued. The explanations of inaction by corporations, which were saying, “We’re against apartheid but oppose sanctions,” sounded increasingly hollow. Ever more frustrated as the FSAM push toward legislation gained force, Sullivan said his principles wouldn’t end apartheid and companies should withdraw from South Africa after the FSAM protests continued.

Ending apartheid had become a dominant civil rights issue, and the legislation that had been introduced by Congressman Ronald Dellums, supported by the members of the Congressional Black Caucus in the House, and piloted through the House by Congressman Howard Wolpe, chair of the House Africa Subcommittee, passed. President Reagan’s September 29, 1986, veto was overridden by the House on October 2, while Coretta King, Jesse Jackson, Randall Robinson, and others sat in the gallery and CBC members prowled the Senate floor as the veto was overridden 78–21. The Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986 became law. Soon Britain and the European Union would also pass sanctions.

The Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986 banned new U.S. investment in South Africa, sales to the police and military, and new bank loans except for the purpose of trade. Specific measures against trade included the prohibition of the import of agricultural goods, textiles, shellfish, steel, iron, uranium, and the products of state-owned corporations. The legislative work was not over. Representative Charlie Rangel (Democrat-New York) in 1987 successfully added an amendment to the Budget Reconciliation Act prohibiting US corporations from receiving tax reimbursements for taxes paid in South Africa. This meant that these corporations essentially had to pay double taxation until they extricated themselves from South African apartheid.

The apartheid system remained in place, but not for long. Resistance continued. In February 1987, the United States and Britain vetoed a UN Security Council resolution that would have made the sanctions imposed by the 1986 act international. In 1988, South Africa detained thirty thousand people without charges, arrested thousands of children, and banned every civic and political organization. Consistent with its constructive engagement policy, the Reagan administration used every loophole in the 1986 law to work in favor of the South African economy.

By September 1988 the House passed HR 1580, the Anti-Apartheid Amendments of 1988. Even though Shell Oil Company funded a vigorous lobbying campaign against the sanctions bill that was also supported by Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s British government, the bill passed, but with a strategic loss. The bill mandated disinvestment. However, the Senate voted to permit US aid to South African-backed forces in Angola, which meant indirectly giving to South Africa through funding the continued conflict and supporting South African-backed forces there.

The South African government tried to fake out the antiapartheid forces by appearing to reform again. In February 1989, P. W. Botha resigned as head of the ruling National Party and was replaced by F. W. de Klerk. Government representatives began to meet openly with representatives of the ANC. Like the ANC, FSAM feared that the political leadership in Congress would accept de Klerk’s leadership as fundamental change in the apartheid regime. We felt that we had to do everything we could in solidarity to expose this effort by the apartheid regime to only appear to make changes.

Unsurprisingly, none of the FSAM leadership had been allowed in South Africa since the protests and the passage of sanctions. Even when Desmond Tutu invited us to his installation as archbishop of Cape Town, none of us could attend. In February 1990, I was permitted to join Jesse Jackson; his wife, Jacqueline Jackson; the novelist John Edgar Wideman; and H. Beecher Hicks, pastor of Metropolitan Baptist Church in Washington, DC, in wangling permission to visit by persuading the ambassador, Piet Koomhof, that if we found progress, we might have something positive to say. When we got there, we went all around the country, accompanied by a large press contingent, speaking, meeting with activists, demanding to see Mandela, and calling for the release of political prisoners.

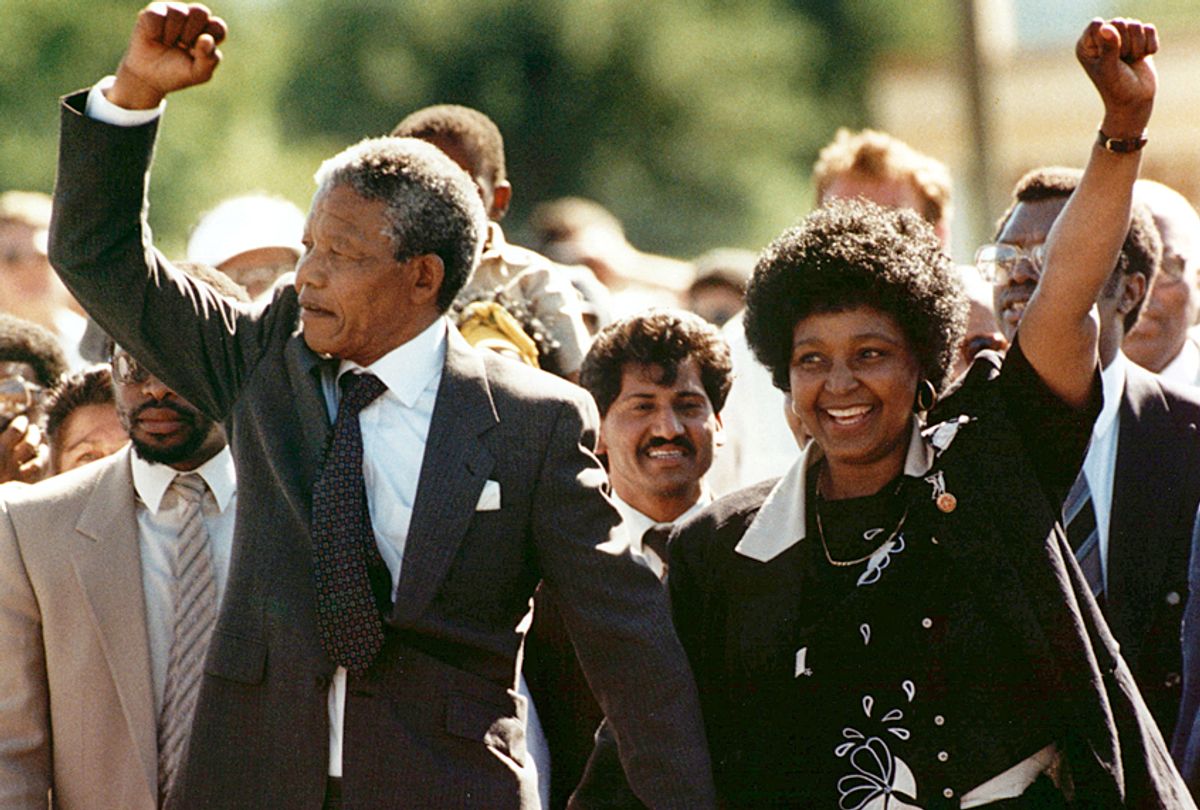

The government informed us on the evening of February 10 that we could essentially stop agitating because Mandela would be freed the next day. On February 11, at about 7 p.m. South Africa time, the waiting for Nelson Mandela, which had been a constant companion most of my adult life, came to an end. On February 11, 1990, after spending 27 years in prison, he was released. There our group was in the Cape Town City Hall to greet him, with the mayor and his official welcoming coterie. Leading antiapartheid activists Allan Boesak and Frank Chikane were also there, as were Mandela’s prison compatriots, Raymond Mhlaba and Walter Sisulu, accompanied by his wife, Albertina Sisulu. Also there waiting quietly were Mandela’s daughter, Zindzi, and his youngest grandchild, Bambata, still a babe in arms, and Mandela’s mother and sister.

The speech he gave at the Cape Town City Hall reemphasized the need for struggle and for sanctions until the end of apartheid and the institution of democracy. His manner and demeanor, the favorable press, along with continued resistance, seemed to foreshadow eventual political victory for the foes of apartheid.

The Free South Africa movement organized an eleven-day, seven-city trip to the United States for Mandela and the ANC delegation in June 1990, for which Roger Wilkins had the major responsibility. Thousands of people greeted Mandela and the delegation throughout the seven-city tour. The ANC viewed this visit as an opportunity to demonstrate to the politicians that Mandela and the African National Congress had large popular support and to help raise funds for ANC to establish a new South Africa. Mandela was the fourth private citizen in the history of the United States to address both houses of Congress. This represented a major political achievement, since he and the African National Congress had long been viewed by the State Department as terrorists. After Mandela’s visit, the Free South African movement came to a close, although supporting organizations and individuals continued to work on African and other international issues.

FSAM was a catalyst for making the antiapartheid struggle visible both inside South Africa and around the world. The visual, radio, and print media crossed borders to tell and show this struggle. Witnesses against apartheid, numbering some 5,000 in the United States, made their opposition visible with their arrests. The bravery and momentum of the struggle inside South Africa became the visible example of all that was wrong with apartheid. I still affirm what I said when first asked whether I’d willingly get arrested at the South African embassy: “It is the right time and the right thing to do!”

The Free South Africa movement had to make a place on the U.S. government’s foreign policy agenda for a continent usually ignored. In retrospect, it is clear that the 1984 antiapartheid campaign had an inside and outside strategy. We had some access to political leaders and the process, because some of us had been or were political officials. The people we mobilized did not have routine access to a range of policymakers, and the people on whose behalf we protested had none. As Sylvia Hill best explains, we were not acting because of direct harm we suffered but because of the suffering of others and the use of our taxpayers’ funds, which made us complicit in the suffering. Defeating apartheid would help them, and race consciousness and political solidarity on race issues might occur elsewhere and in the United States, but FSAM had no personal benefit in mind beyond the goals of the campaign.

We showed how to mobilize a movement, but not, Cecelie Counts suggests, how to organize coalitions. Some other leaders and organizations who had labored long in the human rights field resented Randall, TransAfrica, and our movement because it was unlike what had existed. But our secrecy, holding information within a small group, and keeping the demands simple had worked. Some established organizations, seeing ending apartheid as a human rights issue much like, say, the Palestinian question, were uneasy with the race-based arguments we used, analogizing apartheid to Jim Crow and framing apartheid as a civil rights issue. But we thought correctly that defining apartheid as a civil rights issue would embarrass opponents, mobilize constituencies, and likely achieve the passage of legislation.

We forgot when apartheid was overthrown that the only thing South African leadership owed us was thanks for getting sanctions. This reality hit Randall hard. I recall the way Barbara Masekela, who later became South Africa’s ambassador to the United States, put it after Mandela came to the United States, “We did what we needed to do, and that was then and this is now.” South Africa’s postapartheid government would have a government-to-government relationship with the United States and essentially didn’t need a protest movement anymore. We had done our work.

Excerpted from "History Teaches Us to Resist: How Progressive Movements Have Succeeded in Challenging Times" by Dr. Mary Frances Berry (Beacon Press, 2018). Reprinted with permission from Beacon Press.

Shares