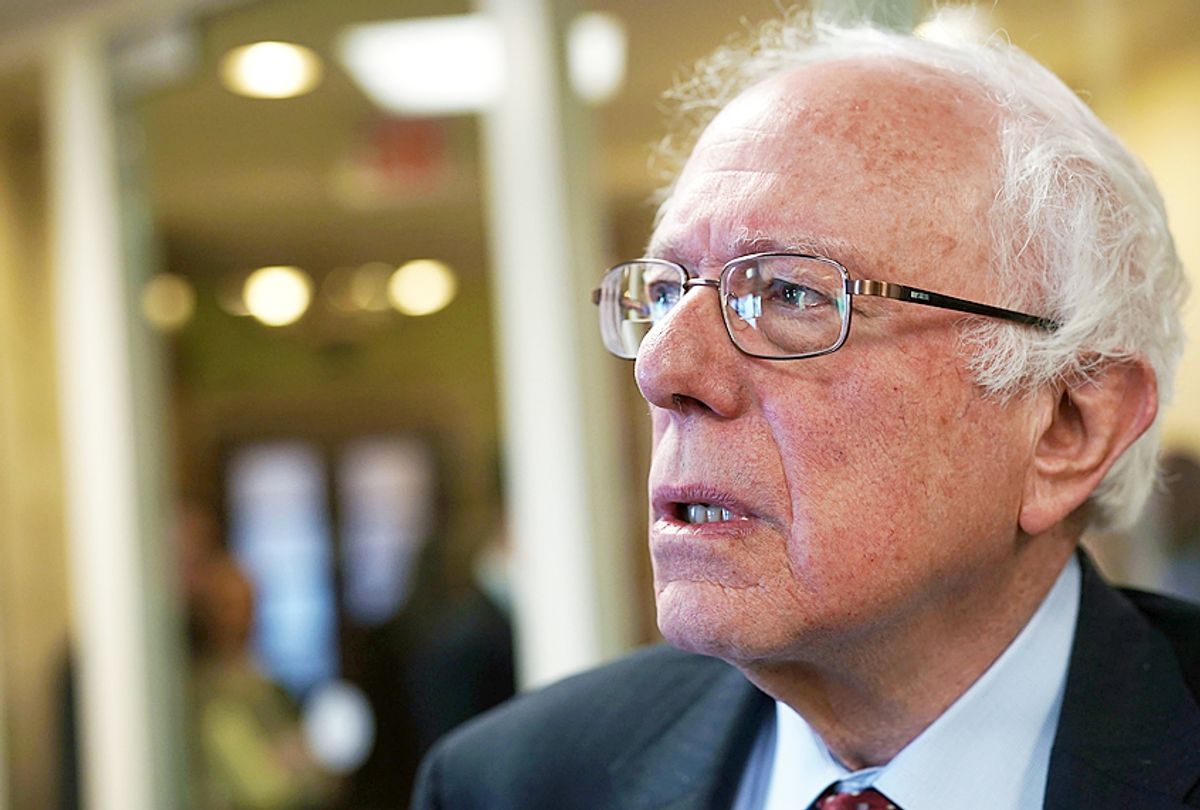

Last weekend, Sen. Bernie Sanders traveled to Texas with a very clear message for progressives in the state: that Texas, long one of the most conservative states in the country, can go blue.

“If you in Texas are prepared to work hard, stand up, fight back, go out to your neighbors, talk to those people who voted for Trump, make sure that every friend you have, and family member that you have, comes out and votes,” the Vermont senator said during a conversation with CNN’s Jake Tapper at the annual South by Southwest festival in Austin, “I believe that Texas can go blue.”

The following day, Sanders held a rally in Lubbock County, where 66 percent of voters voted for Donald Trump in 2016, and during his speech he rejected the hyper-partisan politics that have come to dominate our current era. “I've never believed in this blue-state, red-state nonsense,” declared Sanders. “

This is a point that Sanders has made since his 2016 presidential campaign, and the reasoning behind it is simple enough: The majority of Americans tend to agree with him on a wide variety of issues, particularly when it comes to his economic agenda. This partly explains why he continues to be the most popular politician in the country, despite the fact that he is a self-proclaimed democratic socialist. If Democrats would embrace Sanders’ style of class politics and get behind a bold progressive agenda, the thinking goes, then there’s a good chance that many red counties like Lubbock — and possibly even states like Texas — could turn blue.

While there is a case to be made for this, there is also good reason to be skeptical. We live in the most hyper-partisan era in U.S. history. The red-blue state divide is not “nonsense” but our reality, and partisan hostility has reached historic levels in recent decades, culminating with the presidency of Donald Trump.

Many factors contributed to this trend, and most of them can be traced back to the 1960s, when social movements and major cultural shifts led to a great divergence in America that eventually resulted in the division between red and blue states. The modern Republican Party grew out of this upheaval, and the conservative movement was a political backlash against the counterculture of the 1960s and the various liberation movements (e.g., civil rights, the women’s movement, gay liberation), all of which engendered profound cultural and social changes. The notorious “Southern Strategy,” in which Republicans appealed to the racism of whites in the South to garner votes, is the most frequently cited example of this backlash strategy.

As time wore on, these cultural disputes became more pronounced and personal, and members of the opposite party came to be regarded not so much as political adversaries with differences of opinion but sworn enemies who posed an existential threat to the country. Not surprisingly, bipartisan politics came to look like some quaint historical practice by the time the 21st century rolled around.

Yet bipartisanship never truly died in Washington — at least when it came to economic issues, where bipartisan solidarity was alive and well throughout the 1990s and 2000s. Indeed, it was during the presidency of Bill Clinton that neoliberalism reached its peak, when the Democratic president oversaw sweeping financial deregulation that would ultimately lead to the 2008 financial crisis. There was also bipartisan support behind free trade agreements like NAFTA, which was strongly opposed by labor unions and environmental groups, as well as the welfare reform signed by Clinton in 1996. Big banks and corporations thrived during this period, while wages stagnated for the majority of American workers, driving income and wealth inequality and producing economic instability.

Economic consensus in our hyper-partisan age is hardly surprising if we consider what else happened during the period in which American politics grew increasingly divided on non-economic issues like abortion, guns, gay rights and the like. Starting around the 1970s another shift was occurring in American politics: Big banks and corporations were beginning to accrue political power like never before, infiltrating Washington and flooding the political system with money. As Jacob Hacker and Paul Pierson tell it in their 2010 book, “Winner-Take-All Politics: How Washington Made the Rich Richer — and Turned Its Back on the Middle Class”:

The number of corporations with public affairs offices in Washington grew from 100 in 1968 to over 500 in 1978. In 1971, only 175 firms had registered lobbyists in Washington, but by 1982, nearly 2,500 did. The number of corporate PACs increased from under 300 in 1976 to over 1,200 by the middle of 1980. On every dimension of corporate political activity, the numbers reveal a dramatic, rapid mobilization of business resources in the mid-1970s.

In essence, millionaires and billionaires developed a strong class consciousness during this period, waging an extended class war against the working class behind closed doors. Through political spending, lobbying and various propaganda efforts (e.g., think tanks, political action committees, etc.), Wall Street and corporate America helped establish neoliberalism as the ruling economic ideology in Washington.

Of course, important if somewhat superficial differences have remained between the parties on economic issues (for example, just how low taxes should be on the rich), and while the Democrats may have drifted to the center-right during the '90s, Republicans responded to this by moving still further to the right. Today things have changed slightly from 20 years ago, and with the resurgence of progressives like Sanders and Sen. Elizabeth Warren, the Democratic Party has started to slowly shift back toward the left on economic matters.

But the neoliberal consensus persists to this day, even as political polarization intensifies in many other ways — and as long as money continues to flood the political system, this consensus is unlikely to end. It was all too predictable, then, when the hopelessly divided Congress came together for some good old-fashioned financial deregulation last week, rolling back the Dodd-Frank Act and exempting 25 of the largest U.S. banks from extra regulatory scrutiny. As the New York Times reported:

In a rare demonstration of bipartisanship, the Senate voted 67 to 32 to allow the bill to proceed, setting the stage for a vote this week that rewrites parts of the 2010 Dodd-Frank Act. … Twelve Democrats and one independent sponsored the bill with 13 Republicans. Backers of the legislation hailed it as an example of "old school" lawmaking that harks back to a time when senators regularly worked across party lines.

In response to this bill, Bernie Sanders railed against the Republican-controlled Congress, stating in a recorded video posted on social media: “When we talk about oligarchy and the ability of a wealthy elite to control the economic and political life in this country, we are talking about precisely what is going on in Washington this week, and the power of Wall Street.”

Though bipartisan politics is often hailed as responsible and respectable, there is nothing inherently good about compromise, especially when it ends up serving the economic elite and going against what the majority of Americans want, as is often the case in Washington today when Republicans and Democrats come together.

According to a 2017 poll carried out by Americans for Financial Reform (AFR), 78 percent of likely voters say that “tough rules and enforcement are needed to prevent the kinds of practices that led to the financial crisis,” and 70 percent believe that Wall Street holds “too much influence in Washington under the Trump administration.” It is clear, then, that a majority of Americans would not support last week’s “bipartisan” legislation to deregulate the financial industry.

What this all suggests is that while the red-state/blue-state divide is real and deeply entrenched in American politics, the divide between economic elites and everyone else may be even more consequential in our populist age. Thus, a class politics on the left has the potential to transcend the hyper-partisan politics that characterize our current era. The Sanders campaign laid the groundwork for this strategy, but it is up to progressives and Democrats to implement it in the years ahead.

Shares