Cash built his mythic self to fit his actual voice, behaving as if it had arrived from somewhere else, as if the voice (like a flame) had traveled a great distance to get here. This was correct. As the story goes, Cash’s voice presented itself to him late in his adolescence. It just showed up one day, unannounced, there to be misunderstood and wasted, like any other blessing. His mother was a simple woman but she referred to his voice as The Gift.

Its snarl, however full of bombast and sanctimony it might have been, also had a lazy cruelness to it, a sense of malignant power held in reserve. It was like an ink drawn from some prior place. Cash would always imply that his voice did not come from his own earthly person but from a spectral elsewhere, outside of him, coming on like the Holy Ghost, selecting him and then commencing its ravishing. There was no way he could have prepared himself for its arrival. He had been working when he received it, simply doing his chores, adding his blood and sweat to the family engine, keeping on keeping on. “When I was 17,” he wrote, “I had been cutting wood all day with my father and I came in and I was singing a gospel song, ‘Everybody’s gonna have a wonderful time up there, Glory hallelujah.’”

This was what life was like for Cash, work and song entwined, just the toilsome rituals of another day. When he opened his mouth this time, however, a deep, otherworldly sound burst through. His voice broke into something new, or, to take his own perspective, a different voice broke into him. Things changed. Scratching the lower registers of his new voice, enjoying its strange thick texture, he became for a moment unrecognizable to those who thought they knew and loved him, including his adoring mother Carrie. “I was singing as I walked in the back door,” Cash later wrote, “and she wheeled around from the stove in shock and said, ‘Who was that?’” It seems she thought the sound might be her own father, returned from the beyond.

For Cash, it was an intoxication, a first hint at the life to come: for him to perceive his mother perceiving him and growing confounded in doing so was to realize that he had become, if just for an instant, something unanticipated and strange. He had to have been a stranger to himself in that moment as well, an unfamiliar (this is among the addictions of art). This was the felt strength of The Gift, its vortex and promise, as well as its threat: the possibility that Cash could birth a second self through it, to not just be JR, wayward son of country trash, but to eventually become Johnny Cash, musician and artist, historical and spiritual vessel, consummate American.

Cash decided that he should learn to master this new voice. He went to a local singing teacher, hoping to refine The Gift, but after the first lesson his teacher told him that his voice should not be polished or tamed. Not only was it bigger than he was, it seemed as if his voice had its own ideas about itself, distinct from professional norms. “Don’t ever take voice lessons again,” the teacher told Cash. “Don’t let me or anyone change how you sing.”

In Cash’s version of the story, the voice precedes the man and, in its way, becomes the prophet of his very thoughts. Cash had to expand himself after the voice arrived, burrowing deeper and reaching further, simply to match it. The Gift was always there, driving Cash to bring it proper material. Simply looking inward was not enough. Cash found himself attracted to historical as well as spiritual songs, recurring coordinates of his search for truths that, like his voice, originated from somewhere beyond him, either higher or lower than the topology to which he had been born. The Gift desired truths of a more cosmic quality. “My soul wasn’t born in the cotton patch,” Cash once said. “I think I was just passing through.” Later in his life, Cash recorded his voice declaiming the entire New Testament, unabridged, which is both an unusual way to spend nineteen hours and an acknowledgement of how the holy and the historical came most readily to Cash: in the guise of his own voice.

For Cash to feel or understand a truth, he had to voice it. Instances of this are everywhere. Cash became an advocate for prison reform after the prison albums, as the American Indian ballads that led to Bitter Tears sharpened his sense of political justice. In his first autobiography, "Man in Black," Cash wrote about being present at the personal spiritual testimonies documented in Kris Kristofferson’s “Why Me”–written in response to his own "The Gospel Road" project and Kristofferson’s experiences at Cash’s church–and Larry Gatlin’s “Help Me,” which was debuted at that same Tennessee church Cash and his family attended. When Cash ended up covering these songs in his "American" series, it revealed his voice not only wrapping itself in each song’s pleading devotion but also returning and attending to the moments that produced them, pivots in Cash’s own spiritual development, consecrating them.

Like the Holy Ghost, The Gift had its own itinerary–Cash would follow it. His was a voice that called for mythic histories to buttress it, that petitioned for deep pains to feed and trouble it, that needed great, distant heights for it to call toward. Reading across Cash’s own recollections, it is striking how often he places himself at foundational moments of American musical history, not only providing the opportunity for Kristofferson’s and Gatlin’s songs, but also supplying an anecdote to Carl Perkins about a black airman back in Germany with an inordinate fondness for his own blue suede shoes, inspiring Perkins’ classic recording. In his second autobiography, Cash recalled a desert drive he took with Roger Miller. “Out in the middle of the desert,” wrote Cash, “he told me to pull over, then jumped out, and ran off behind a Joshua tree with a paper and pencil.” When Miller came back, he had the lyrics to “Dang Me” with him, a song that would become one of his biggest hits. “He had to bring it into the world all by himself,” Cash wrote, “like an Apache woman giving birth.” This was how the world revealed itself to Cash. He was one of those who needed to be astonished by first things; to judge them, and to be judged by them in turn.

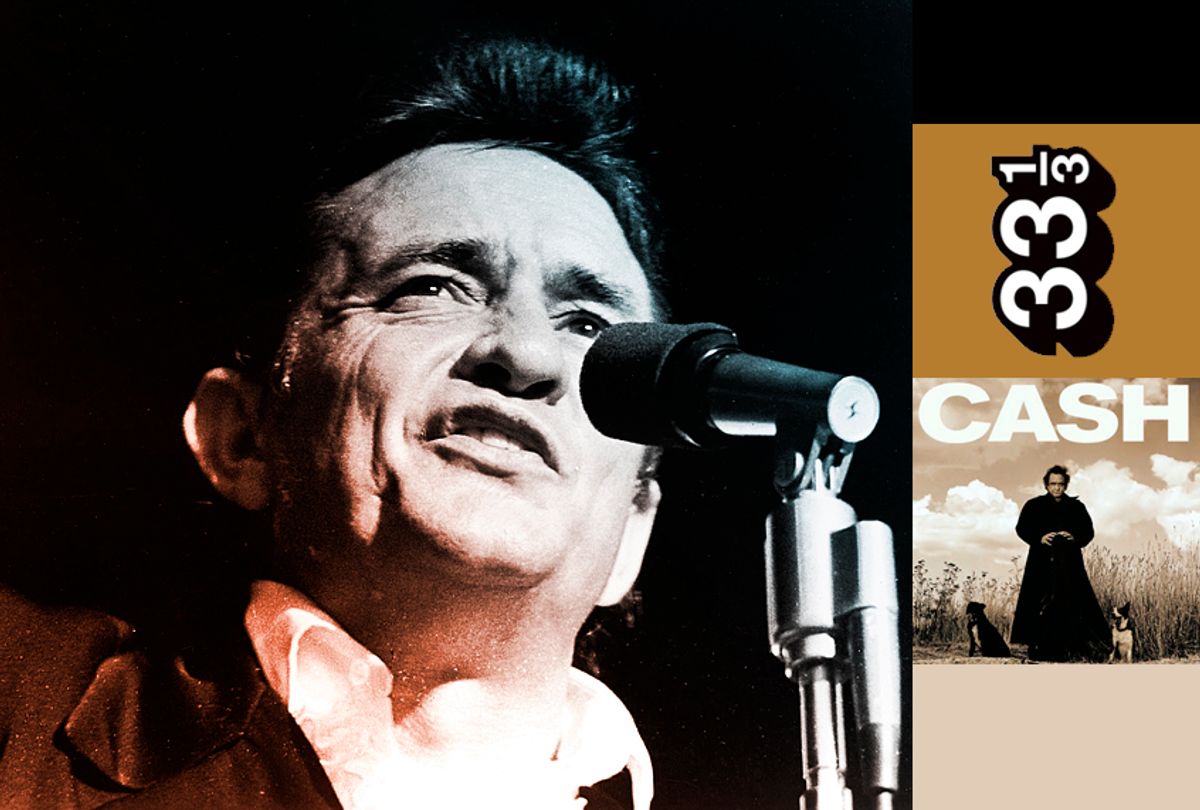

Excerpted from "Johnny Cash's American Recordings" by Tony Tost (Continuum, 2011). Reprinted with permission from Bloomsbury Publishing.

Shares