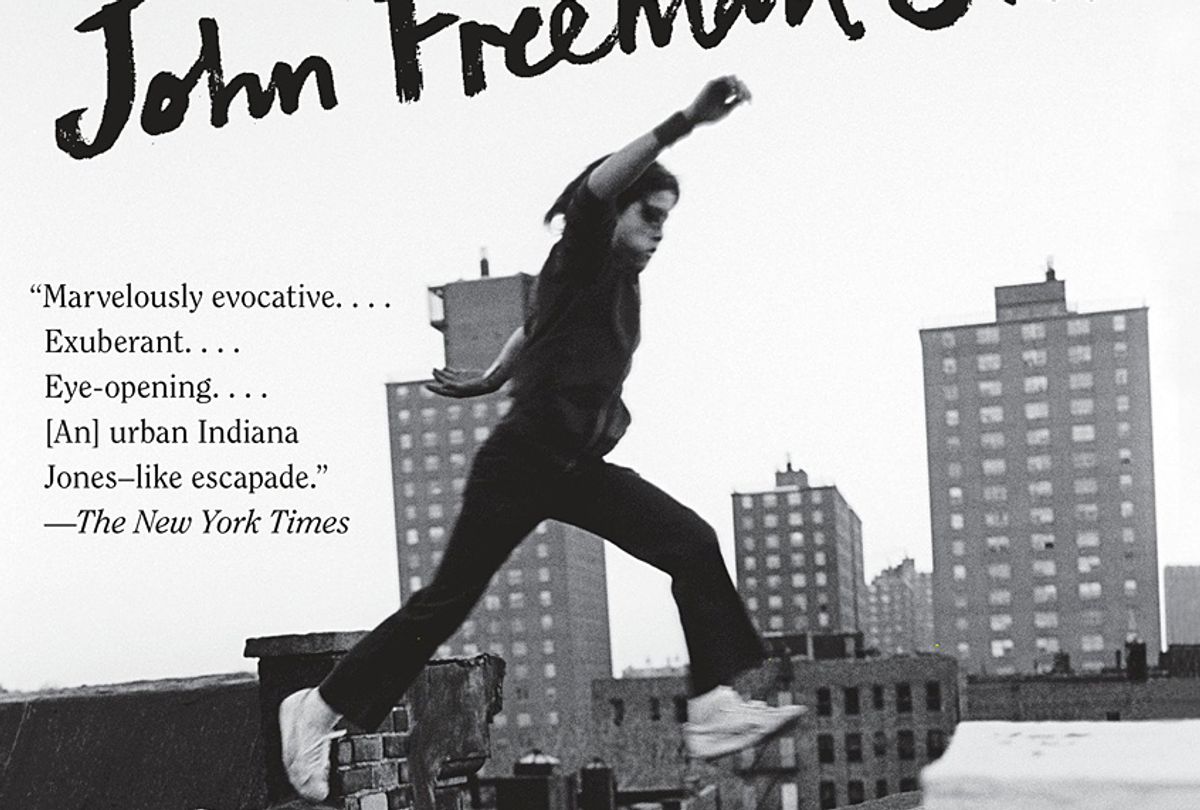

Excerpted from "The Gargoyle Hunters" by John Freeman Gill. Copyright © 2017 by John Freeman Gill. Excerpted by permission of Vintage. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

New York puts you in your place. It’s bigger than you, and more important. It’s older than you, and newer too. It’s more than you: more towering, more gutter-level; more striving, more complacent; more hurried, more arrived; more refined, more depraved; more timeless, more late for dinner reservations. It has a lot of moving parts, and countless immovable ones. And it doesn’t care if you have a relationship with it or not.

But the street walls, the miles of buildings rearing up on either side of you on any major avenue, could be reassuring too. Something you could count on. Without giving it any thought, I’d learned to take these miles of masonry for granted, to feel them holding and even guiding me on my passage through the city, the way a river runner feels embraced by the certainty of canyon walls. Trundling up Amsterdam Avenue in my father’s repurposed old Good Humor truck, the Upper West Side asnooze around us, I felt at ease in the brick-and-brownstone-flanked corridor, block after block of familiar tenement New Yorkness scrolling across my window frame.

And then it ended. Without warning, without transition, the street wall, the buildings, simply vanished, replaced by a moonscape of devastation that made me do an actual double-take of disbelief. The blocks along Amsterdam were the same size as before, but instead of tenements and storefronts, instead of windows and stoops and lives, there were only sprawling expanses of rubble. A neighborhood leveled.

The only exceptions were the side streets, where a few brownstones still stood, huddled together for safety.

“Jesus,” I said. “What happened here?”

“Urban renewal. Twenty square blocks, something like 540 buildings — the city’s knocking it all down.”

“Why?”

“They’re planning a slew of hideous, boxy, brick towers,” Dad said. “What else do they do anymore?”

We hopped a chain-link fence and walked the graveyard of the neighborhood. The crushed, shardy remains, for all their hazardous shifting underfoot, seemed oddly undifferentiated. Wreckage is wreckage, I supposed. In the crunch and stumble of our exploration, eyes fixed cautiously on my next step, I could see no evidence that the acres of jumbled rubble had ever taken the form of anything as solid and reassuring as homes. We were treading an aftermath.

“I never get used to it, no matter how often I come to one of these sites,” Dad said. “It’s like a firebombed city, Dresden or something. Only this time we did it to ourselves.”

There was an archaeological thoroughness to the way he eyeballed the ruins, a forensic sensitivity. As I stood there blinking dumbly at the rubble, he took two unhesitating steps to his right and toe-nudged an unarticulated brown block of rock with his work boot. It flipped onto its back, revealing a carved keystone portrait, the head of a squirrel-cheeked lady wearing a crooked smile and a necklace of inelegant bulbous beads. Aside from her missing nose, she was in pretty good shape.

“Will you look at that!” Dad cried. “Look how transcendently ordinary she is.”

“What do you mean?”

“I mean she’s a regular person. She’s not Athena or Diana or the Queen of Spades.”

“So what?” I asked, and I said it in a challenging, almost pissy voice, trying to get a rise out of him, to get him to notice me. He didn’t.

“Well, the carvers who came over here from Italy and Germany clearly got tired of doing the same old idealized classical or historical figures, so they started sculpting people they knew, barkeeps and cops and dock workers.” He regarded the woman’s face closely. “This gal is way too funny-looking to be a goddess. She’s probably the carver’s sweetheart, or maybe a barmaid he’s got a crush on. And he honored her, you know? He did a really loving portrait. She’s got a good smile, I think: skeptical but generous. Here, help me get her back to the truck.”

It was a bit of a schlep to our next destination. Up on 95th, near Columbus, a brownstone had had the bad luck to share a wall with a tenement demolished by the wrecking ball. The vibrations had destabilized the house, which was now slouching toward the rubble heap to its west, as if seeking to join it. The house’s listing brick side wall had been braced by a cluster of wooden emergency supports, nine pale, upflung arms pushing back diagonally against its will to fall.

“Lucky for us,” Dad said, “they evacuated the family that lives here. They won’t let them back home till the place passes inspection.”

“Will it collapse?”

Dad shrugged. “Who knows? I doubt it.”

Part of the troubled wall was protected by some kind of tarp or tar paper. Sensing weakness, Dad peeled back one of its lower corners and found a slanty crack and a small, street-level hole near the back of the building, where a bunch of bricks had fallen away.

He sent me through the hole with a flashlight, which I immediately trained on the inside of the wall I’d just come through. A fierce crack, an inch wide, zigged down its plaster from the ceiling to about the height of my chest. But if you ignored that one menacing detail, it looked to be a fairly ordinary old brownstone, with a crooked spine of staircase twisting up its center and a pair of small, worn-out Pumas left on its bottom step by some sighing mom who probably wanted them brought upstairs, for God’s sake, how many times do I have to ask you?

Dad was waiting at the back door when I opened it, his leather-edged canvas plumber’s bag in one hand.

“Do come in,” I said with a low bow. “Make yourself at home.”

“Don’t mind if I do.” He stepped in and stomped his boots on the Welcome mat, a Dad-shaped aura of dust puffing from his body. “Lovely place you’ve got here.”

We were standing in a drab, old-fashioned kitchen right out of The Honeymooners. Dad handed me a chair to carry and led me up the stairs with his flashlight into the second-floor room facing 95th Street. It looked like some kid’s bedroom, probably a little boy’s. It had a bunk bed with no sheets on the top bunk, a Snuffleupagus comforter on the bottom, and a pink-plastic Big Wheel parked at its foot. A few feet away, the side wall had a long, vicious crack in its plaster, a lot like the one downstairs.

Dad found a bedside lamp and switched it on.

“There’s something here we want?” I asked.

“Sure is. Intact and everything. But first we’ve got to build a form exactly the shape of that window frame. To support the arch.” He nodded toward the window on the left, whose enframement was a tall rectangle with a gentle curve at the top.

What Dad nailed together next was something of a domestic collage. He cut up the kitchen chair with his circular saw, but he needed lumber of other sizes and shapes too, so he kept sending me around the house to find whatever wood I could: bureau drawers, the footboard from the master bedroom, a pair of sink-cabinet doors from the hallway bathroom. The stroke of genius, the scavenged wood I could see made him most proud of me, was the base of the boy’s rocking horse. I pointed out that it had almost the exact same curvature as the top of the window frame (upside-down, of course). Dad laughed with pleasure, amputated it with his circular saw, and nailed it atop the form.

“Perfect fit,” he said, when we’d hoisted our mongrel creation into the window opening. “Now that’s what I call an arch support.”

We slid the kid’s bunk bed lengthwise in front of the window to use as a scaffold. Dad climbed to the top bunk with a red Magic Marker and drew a horizontal rectangle on the plaster directly above the window. I handed up his tool bag and joined him. We sat on the top bunk side by side with our legs hanging over, chipping away at the wall with hammers and chisels. When all the plaster was removed from within the red Magic Marker rectangle, we started in on the brickwork behind it.

“What we’re after, of course, is the keystone, in the center of the arch,” Dad told me. “But to get to it, we’ve kind of gotta take the wall apart around it. Most of these brownstones were built in layers, see? Their structural walls were made of three wythes of brick.”

“When you say three widths, you mean the bricks are back-to-back-to-back?”

“Wythes, not widths: W-Y-T-H-E-S. It just means layers. And yeah, they’re back-to-back-to-back, with the keystone set into the face of the building usually just two wythes deep. You and I are gonna focus right now just on the innermost wythe.”

The mortar was really crumbly, freeing up the bricks pretty easily. One by one, they fell away, landing with muffled thumps on the kid’s green carpet.

He told me to keep at it, and he headed downstairs.

It was messy work chiseling away the bricks, but not too difficult. In less than half an hour I’d chipped away the first brick layer from the Magic Marker rectangle above the window. Behind it waited another layer of bricks — except in the center, where I had exposed the back of a rough-hewn, chocolate-brown wedge of rock. A thin metal strap protruded horizontally from its top, where it had been embedded for something like 90 years in the mortar layer I’d just chipped away.

“There’s your keystone!” Dad said when he came back. He handed up a pair of pry bars. “Now to free it up.”

He joined me on the top bunk, and the two of us went to work on the remaining two layers of brick on either side of the keystone, using the pry bars to chip away the mortar and prize out the bricks. Before long, we had both poked through to the outside world, creating a pair of ragged windows through which you could make out the hunkered shapes of two undemolished brownstones across the street. Their own keystone gargoyles scowled back at us.

All that remained to liberate the gargoyle keystone was to chisel away a couple rows of brick directly above it, along with the line of mortar just beneath it. When we’d done that, the keystone was all but freestanding, its bottom supported by the jury-rigged wooden form. Together we pushed the bunk bed right up snug against the window and then, kneeling on the top bunk, put our arms around the gargoyle and hugged it roughly into the room.

What it must have looked like had anyone been watching us from the street, I can only guess: the silhouette of a single unnamable mythological monster, maybe, with a wedge-shaped brown head, two man arms and two boy arms, gripping its own face in the middle of a ruptured wall.

When the keystone finally broke loose, it tipped backward and fell onto the bunk bed, gently cratering the mattress between us. It was oddly intimate, the three of us so close together after all that struggle, and the roguish character staring up at me from the keystone made me laugh. He was a smirking, blunt-nosed man whose cauliflower-shaped head was elaborately turbaned with bandages, as if some well-meaning friends had swaddled his poor noggin in dish rags after a barroom beat-down.

“Ha!” Dad exclaimed. “Just look at that irreverent spark in the pugilist’s eye, that undimmed commitment to mischief. Is it just me or — yes! His eyes are popping, Griffin!” He cupped the stone chin in his hand, looking into the gargoyle’s pupils. “That’s extraordinary! The carver put lumps in his eyes to make them more expressive.”

He met the carved face’s gaze with his own. He did not blink. A minute passed.

“The bridge of time is very poignant,” he told me. “I think about the immigrant carvers who came over here in the 19th century and did this work on people’s homes — itinerant nobodies, many of them, with no stable homes of their own — and I meet them across time.”

Shares