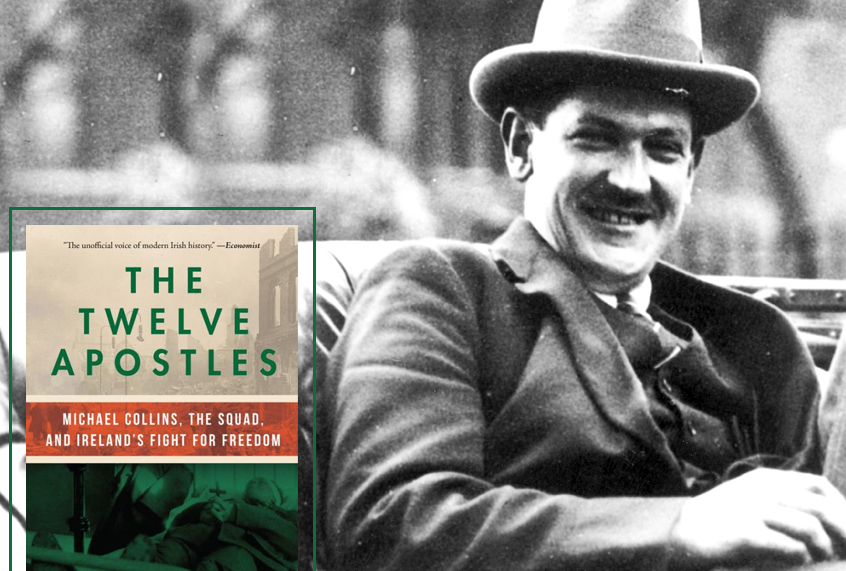

Excerpted with permission from The Twelve Apostles: Michael Collins, the Squad, and Ireland’s Fight for Freedom by Tim Pat Coogan.

It is my contention that Michael Collins was one of the most extraordinary men ever to have been born in Ireland. Collins’s remarkable qualities – as a man, a citizen, a commander and strategist – shine through the years; and to me, they gleam all the more brightly in this centenary year of the 1916 Rising. Almost thirty years ago, I wrote my biography of Collins – and he remains a major focus of my research today, because now I want to examine in detail one of his most extraordinary, and certainly most controversial, creations.

This was the Squad, or the Twelve Apostles: the names given to a small undercover unit controlled by Collins which operated in Ireland during the final era of British rule from Dublin Castle. It is crucial to note that the Apostles were by no means superbly resourced – indeed, the opposite is the case: the unit was only ever lightly armed: the original .38 pistols held by its members were eventually swapped for rather more powerful but still essentially modest .45 revolvers – and in such improbable fashion, these individuals took on the forces of a state that was equipped lavishly with artillery, machine guns, rifles and tanks. The real firepower of the Twelve Apostles, however, originated elsewhere, from sources that the state could neither control nor eliminate: from widespread public support among the Irish in Ireland and abroad (especially in the United States); from sheer idealism; and from an enormously potent intelligence-gathering operation that was also masterminded and run by Collins himself.

Collins was a difficult man. He let off steam by wild bouts of furniture-smashing and wrestling matches. He was given to practical jokes that were not all that funny. He had a volcanic temper, and he could be bullying. Yet he was the Squad’s alpha and omega; the story begins and ends with this fascinating and controversial character. One man’s freedom fighter is, after all, another man’s terrorist – and nobody in modern Irish history encapsulates this slogan more fully than Collins, who can well be described as both a freedom fighter and a terrorist.

Indeed, Michael Collins was a walking contradiction of a man. He was both an idealist and a realist, with the two conflicting parts fused together by his genius and his incredible energy, his ruthlessness and his compassion. His idealism had taken him into Dublin’s General Post Office during the 1916 Rising, but the first of his reasons for forming the Squad is contained in recollections following this traumatic week in Dublin. He told his friend Kevin O’Brien (as I record in my biography “Michael Collins”) that:

It is so easy to fault the actions of others when their particular actions have resulted in defeat. I want to be quite fair about this – The Easter Rising – and say how much I admired the men in the ranks and the womenfolk thus engaged. But at the same time – as it must appear to others also – the actions of the leaders should not pass without comment.

They have died nobly at the hands of the firing squads. So much I grant. But I do not think The Rising week was an appropriate time for the issue of Memoranda couched in poetic phrase, nor of actions worked out in a similar fashion. Looking at it from the inside (I was in the GPO), it had the air of a Greek tragedy about it, the illusion being more or less completed with the aforementioned memoranda. Of Pearse and Connolly I admire the latter the most. Connolly was a realist, Pearse the direct opposite. There was an air of earthy directness about Connolly. It impressed me. I would have followed him through hell, had such action been necessary. But I honestly doubt so much if I would have followed Pearse – not without some thought anyway. I think chiefly of Tom Clarke and Mac Diarmada. Both built on the best foundations. Ireland will not see another Seán Mac Diarmada. These are sharp reflections. On the whole I think the Rising was bungled terribly, costing many a good life. It seemed at first to be well organised, but afterwards became subject to panic decisions and a great lack of very essential organisation and cooperation.

Collins, then, had not only participated in great and stirring events. He had watched too – and he had learned. He had made up his mind that in the new round of fighting, not merely should that round not be bungled – it must be a new form of resistance. There was to be no more “static warfare” such as had been witnessed across Dublin during the Rising, consisting as it did of taking a strong point and holding on gallantly until superior numbers and firepower inevitably crushed the insurgents. This was certainly stirring to behold and support – but it was doomed to fail.

In addition, Collins had witnessed the political detectives going about the room full of captured prisoners in Richmond barracks in Dublin, identifying the rebel leaders for the British Army – and for the firing squads. It was a grim lesson in the importance of intelligence, of the political police or “G-Men”, and of the machinery of repression that held the country – and this was only underlined further for him when an intelligence officer in Dublin Castle, Edward – Ned – Broy, smuggled him into Brunswick Street police station one evening. Collins spent a crucial night here sifting through the police records which demonstrated how the collection of political intelligence was an essential tool in the maintenance of British control. Later, his thinking and planning would justify the ruthless means by which he put an end to that control.

In an interview with me, Vincent (Vinnie) Byrne – one of the Squad’s most celebrated members – told me:

We were all young: 20–21. We never thought we would win or lose. We just wanted to have a go. We would go out in pairs, walk up to the target and do it, then split. You wouldn’t be nervous while you would be waiting to plug him, but you would imagine everyone was looking into your face. On a typical job we would use about eight, including the backup. Nobody got in our way. One of us would knock him over with the first shot, and the other would finish him off with a shot to the head. Collins was a marvel. If he hadn’t done the work he did, we would still be under Britain. Informers and drink would have taken care of us, but our movement was temperate. Collins would meet us from time to time and say, you’re doing great work, lads. There was no formality about him. I remember after the Irish government was set up, I was on guard duty at Government Buildings, and he was Commander in Chief. He saw me and came over to me and put his arm around me and said, How are you going on, Vinny?

And his colleague and friend Frank Thornton summed Collins up thus:

Mick Collins was the ideal soldier to lead men during a revolution such as we were going through and I think all and sundry whether they subsequently fought against him in the civil war or not who had close contact with him, must admit that he was the one bright star that all the fighting men looked to for guidance and advice.

In addition, the story of Collins and the evolution of his reputation has been marked, shaped and at times stunted by the context against which twentieth-century Irish history unfolded. For decades after Collins’s death (in August 1922, at the age of thirty-one), his most formidable adversary held power in Ireland – and Éamon de Valera saw to it that his own reputation was extolled, most thoroughly, and to the detriment of Collins and his legacy. Indeed, a cross erected over Collins’s grave by his brother Johnny at Glasnevin Cemetery was only permitted on a reduced scale and to a design sanctioned by de Valera himself; and Collins’s name was excised from an official government handbook produced on the fiftieth anniversary of the 1916 Rising.

So long as de Valera’s palsied hands gripped the reins of power, moreover, representatives of the Irish Army, of which Collins was the first Commander-in-Chief and within the ranks of which Collins’s memory was held in the highest regard, were not permitted to attend the annual commemoration at the place where he was killed, Béal na Bláth in West Cork. Indeed, it was not until 1990 and the centenary of Collins’s birth (when incidentally, I had the honour of delivering the commemorative oration), that an Irish Taoiseach permitted Irish Army personnel to attend.

This mean-spirited and ungenerous treatment at home did not, however, affect Collins’s reputation as a guerrilla leader abroad. Take the example of one of the most ruthless and successful guerrilla movements of the twentieth century, which led eventually to the creation of the state of Israel in what had been the British Mandate of Palestine. The Jewish leader Yitzhak Shamir both studied the methods of Michael Collins, and used the code name Michael as his own nom de guerre. And in the state of Israel which Shamir helped to form, I was made aware of a guilty foreboding on the part of those Israeli citizens who knew their history, that one day the Arabs too might produce a Michael Collins – and that if they did, there would not be a supermarket left standing in Israel.

During his lifetime too, there was no shortage of observers who knew exactly what Collins was capable of achieving, and what he might do with his energy and talents – and in the years that followed his death, many individuals were more than prepared to learn from Collins and from the methods he deployed. Imitation is, after all, the sincerest form of flattery – and his British adversaries paid him the supreme compliment of importing Collins’s tactics and adopting them in their own covert military operations. When the Special Operations Executive (SOE) – sometimes known as ‘Churchill’s toy shop’ – was established at the onset of the Second World War, Winston Churchill envisaged the force ‘setting Europe ablaze’ through the use of such distinctly Collins-esque methods as assassination and sabotage.

The SOE was tutored in Collins-patented methods by Major General Sir Colin Gubbins, a prime mover in the British forces of the time, who described his experience of service in the Ireland of the 1920s as ‘being shot at from behind hedges by men in trilbies and mackintoshes and not being allowed to shoot back’. Irish survivors of the Anglo-Irish War, particularly wounded ones, were left in some puzzlement as to where the bullets did come from. But there is no mystery about the fact that in later years, Gubbins would lecture the SOE on the lessons of his Irish service, warning them in particular to leave no documentation behind them and commit as much as possible to memory. Gubbins knew what he was talking about: Collins and the IRA devoted much time and energy to the capture of British documents; and, towards the end of the conflict, the British benefited from the capture of pieces of Collins’s own paper trail.

Gubbins drew many of his recruits from the British public school system – but the individuals who comprised Collins’s elite, or Twelve Apostles, were members of a rather different tribe. They were largely working-class men and women whom he sculpted into a hidden army that drove a spear into the heart of an empire. He commanded them by force of personality, for in addition to the difficult and tempestuous personality I have mentioned above, Collins possessed something – one might call it the X Factor – that explains more than a thousand military manuals ever could how he wielded that empire-wounding spear. In the words of Frank O’Connor, whose biography The Big Fellow (1937) allows the sheer humanity of this public figure to shine through, Collins took:

the simplest men, men to whom no man in the world had ever attached importance to, and made them feel that the smallest task they performed was a matter of life and death. Before him, after him, none could give them the same sense of responsibility, and their devotion to him was no greater than his to them.

As for the members whom he controlled and commanded: these individuals performed dark and brutal deeds, and when the Anglo-Irish War was over some of them performed even darker ones. War, after all, can never be sloughed off: on the contrary, it has a habit of affecting the winners just as much as the losers. Yet this small band captured the imagination of large swathes of the Irish public. The idea that the Lilliputians, after centuries of conquest, could at last strike back successfully against an enormously stronger foe: this sense overlaid the grimmer realities of war and strife with a patina of romance that has still not faded – even if contemporary Irish attitudes towards militarism generally tend to be more critical and analytical than of yore.

Change is effected, and history made, by a combination of will and circumstances. Collins had the will: and in the circumstances of his day he and the Squad altered the course of Irish history. The world has changed much in the century since Collins and his Apostles took on the authority of the British state in Ireland. The echoes of the bombings and shootings in Northern Ireland have largely died away since the conclusion of the Good Friday Agreement in 1998: and as we have lately seen, the Republic’s decision-takers have deemed it safe to allow the people to take ownership of the commemoration of the centenary of the Easter Rising – unfettered by doubts and fears of what reaction this might elicit from either Conservatives at Westminster or Unionists in Ulster. Michael Collins and his Apostles played a vivid and, in the end, decisive, role in the history of the years that we are now committed to remembering.

Excerpted with permission from The Twelve Apostles: Michael Collins, the Squad, and Ireland’s Fight for Freedom by Tim Pat Coogan. Copyright 2018 by Skyhorse Publishing. Available for purchase on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and Indiebound.