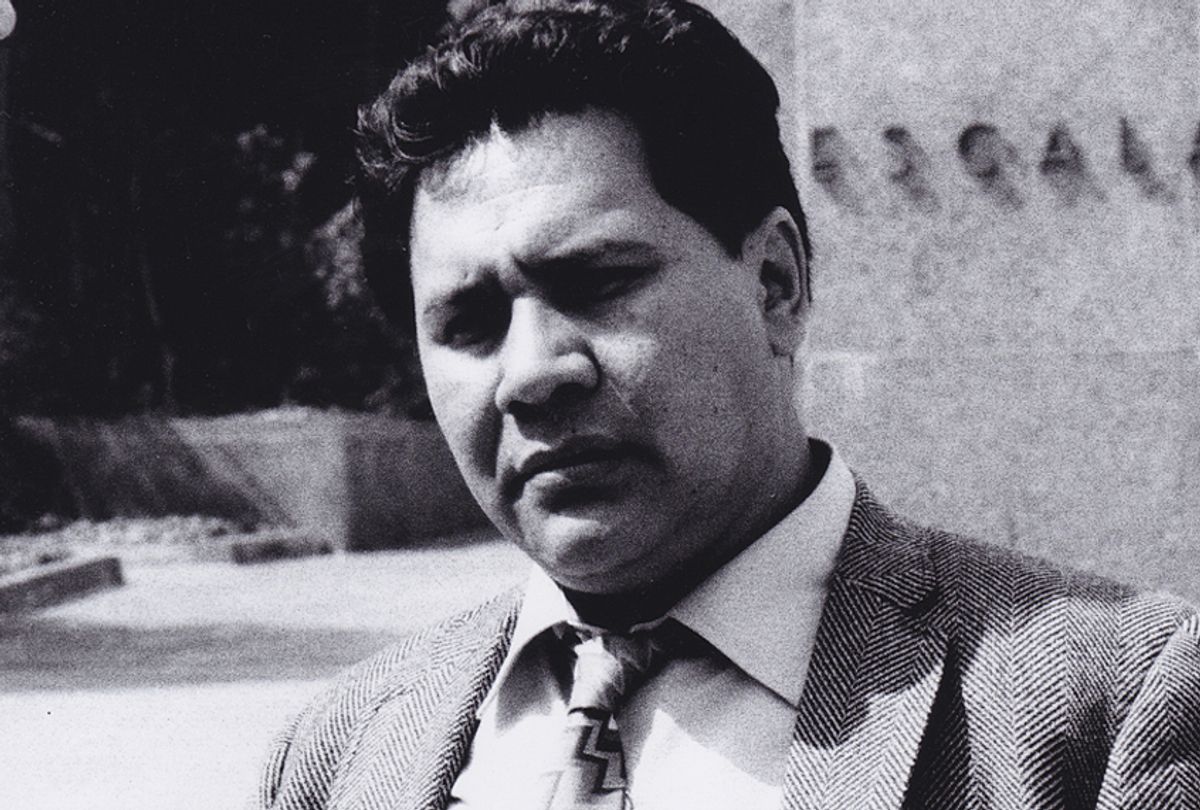

In Phillip Rodriguez’s new PBS documentary "The Rise and Fall of the Brown Buffalo," Oscar Zeta Acosta — the Chicano Rights author, attorney and activist who Hunter S. Thompson would depict in his 1971 work "Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas" as Dr. Gonzo — immediately takes center stage: in footage from an East Los Angeles rally against police brutality, Acosta, dressed in a broad cowboy hat, exclaims to the crowd: “Our representatives are not in the government, this is not our government, and the sooner we get that straight in our heads, the sooner we’ll get together. Or else they’re gonna keep on killing us. I swear to god they’re gonna keep on killing us. They’re gonna wipe us out!”

It’s a deeply affecting clip: suddenly and starkly — rising up as if from the proverbial projector itself — Acosta has returned (just when we need him most) to offer a warning to us all.

However, what’s noteworthy about this upcoming documentary is that, throughout the hour-long storyline, Rodriguez repeatedly weaves historical footage with re-created, live-action scenes. What results is an astonishing, genre-bending work of creative storytelling that also happens to be deeply rooted in years of verifiable research.

"The Rise and Fall of the Brown Buffalo" reclaims Acosta as a brilliant political, legal and authorial force who challenged societal and institutional injustice at every step — someone who understood, from the start, the price his dissent would demand. In this sense, the film raises a question that feels especially pertinent today: how do you fight back against people who, because of the enormous power they’ve acquired, consider themselves and their institutions above the law?

For Oscar Acosta, the answer was as simple as it was stark: by risking everything — including, if necessary, your life.

The first portion of the film settles on Acosta’s upbringing in the small, heavily segregated town of Riverbank, California, an experience that would prove foundational to his heightened awareness of class and race. We also bear witness to his time in the Air Force and, afterward, in San Francisco in the early 1960s, as well as his struggles with faith, family, psychiatric treatment, writing, law school, and the bar exam, which he’d pass in June of 1965.

For the next two years Acosta practiced as an attorney in Oakland as part of Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society initiative — helping, day in and out, the poorest members of the community — until, in 1967, disillusioned and worn out, he’d quit his job and drive east, lighting out for parts unknown.

Eventually he arrived in the remote town of Aspen, Colorado. On a cold July evening he walked into a bar and, as the film depicts, announced to the patrons there — which happened to include a 30-year-old journalist who’d recently published his first book (about the motorcycle gang the Hell’s Angels) — that he was, in fact, the trouble they’d all been spending so much of their lives waiting for. The Brown Buffalo, Acosta called himself.

“Oscar had different values than anyone else in town,” one of the attendees that night would later relate. “He was socially conscious, and we were not.”

Hunter S. Thompson was intrigued. The rest of the evening the two of them would talk — about politics, about San Francisco, about the future of the country — and from that point on, Acosta and Thompson would be inextricably linked, each one challenging the other intellectually at every chance. "The Rise and Fall of the Brown Buffalo" harnesses this tension by deftly re-creating — via its use of contemporary actors (Jesse Celedon is charismatic as Acosta, and Jeff Harms offers a delightfully subdued version of Thompson) their political dialogue — which has been drawn for the most part from their extensive correspondence.

I won’t spoil the pith of these exchanges — Rodriguez, working with the film’s writer, David Ventura, renders them vividly — but it’s fair to say that the central point of contention can be summarized as such: is it better to work within the democratic means of our republic to effect change, or have things become so institutionally unjust that the only way forward is to tear the whole thing down and start again? In other words: should we rely on electoral agency (Thompson) or revolution (Acosta)?

Their intellectual relationship would culminate around their shared outrage toward the blatant abuses being perpetrated at the time by Los Angeles law enforcement: on August 29th, 1970 the prominent journalist Ruben Salazar was murdered by a sheriff’s deputy during an all-out police riot — an event that Thompson, due to Acosta’s insight and connections, would eventually render into an intricate, 19,200-word article for Rolling Stone (“Strange Rumblings in Aztlan”) that ruthlessly and systematically indicted the police-state mentality of L.A.’s cops; in hindsight, it’s an article that remains one of Thompson’s very best.

But to be clear: while Hunter S. Thompson’s friendship with Oscar Acosta remains central to this documentary — for fans of Gonzo Journalism and of Thompson in general, :The Rise and fall of the Brown Buffalo" is a must-see film — Phillip Rodriguez is first and foremost telling a story that hasn’t yet been fully articulated: the role that Oscar Acosta played, for a brief but brightly delineated stretch of time, in our larger American narrative of political and cultural change.

There’s so much more I’d like to say about this remarkable documentary — about its all-Latino production crew; about its lucid depiction of the Chicano Rights Movement and the formation of groups like the Brown Berets; about Acosta’s brilliant legal challenge to the entire Los Angeles Superior Court Grand Jury system; and about the scene early-on (one of my very favorite) in which Oscar Acosta and Hunter Thompson drive to Judge Arthur Alarcon’s house in L.A. and Acosta, using gasoline, lights the entire lawn on fire, all the while reciting word-for-word the famous quote by Jesus in Luke’s Gospel on the hypocrisy of the law (“Woe unto you also…”) — however, in anticipation of the premiere, I think it’s important to keep in mind two quotes.

The first is from the middle of the film: “The persons that make the law,” Acosta intones, “the persons that enforce the law, they fall into one pattern: they are white, and they are rich, and they are old.”

The second is from near the end; standing at the window of a forlorn 1974 Mexico hotel room, Oscar Acosta proclaims: “What is clear to me is that I am neither a Mexican nor an American. I am a Chicano by ancestry and a Brown Buffalo by choice. And I suspect the gods of war are not yet through with me.”

Shares