I can’t lead that kind of life. I’d feel like a bird in a cage. . . . There’s no way in the world you can keep somebody from killing you if they really want to kill you. — MLK, responding to a plea that he travel with bodyguards, Albany, Georgia, March 23, 1968

Exhausted at the end of a day of travel and high-stakes meetings, King returned to his room to rest. Despite his outward calmness at the time, the bomb threat to his flight that morning was still eating at him. That would become painfully evident in an emotional speech that he would deliver that night.

The bomb scare appeared to have struck him as a dire warning about the perils awaiting him in Memphis. If he could not say who or when someone might attack, he knew that he was in mortal danger. Would his assailant be an extremist pro-war hawk aggrieved by his denunciation of U.S. policy in Vietnam? Might it be a law-and-order zealot outraged by his vow to hound and disrupt Washington for the poor? Perhaps a trigger-happy racist inflamed by loathing for him and everything he personified? Or a Black Power fanatic targeting a man he perceived as an anti-revolutionary?

Being in Memphis was doing nothing to allay King’s fear. The city was very much on edge, the racial tensions from the strike sharpened by continuing bitterness over the riot and the harsh police response to it. Anxiety was in the air, and King was being swept into it. John Lewis, the young movement leader who was working in tandem with the SCLC, was hearing reports from people close to King that he was seized by dread. Lewis would later recall learning that King was anguished by “the ugliness and killing that was rising up all around him. He could feel it closing in.”

King’s fear for his safety in Memphis was in no way alarmist. It was well founded, as the police were aware. Even before King’s visits to the city on March 18 and March 28, the Memphis police were fielding threats against him. According to Memphis police director Frank Holloman, police headquarters and other city agencies had been receiving calls warning that “something was liable to happen to Dr. King."

Holloman nevertheless decided against providing security for King on either March 18 or 28. In congressional testimony in 1978, Holloman explained why. He said of King: “He was just another person who was involved in the sanitation strike, and there was no reason, apparently, that we even thought of providing security for him.”

Nor did the Memphis authorities notify King of the threats against him. Or so it appears. In his testimony before the House Select Committee on Assassinations about the police handling of King’s security, Holloman did not mention any such warnings having been conveyed to King in mid- March. More threats had poured in after the March 28 riot. The police evidently did not warn King of those threats either. An after-action report prepared by the police department detailing hour-by-hour the surveillance and security surrounding King’s presence in Memphis on April 3 and 4 says nothing about warnings to him.

It would seem that the bomb scare in Atlanta might have prompted him to request police protection in Memphis whether or not he knew of the threats. But he did not request a police bodyguard in Memphis. He rarely sought police protection, yet he feared that he could die a violent death at any moment.

He tried to buffer his fear by developing a numb fatalism, a defense against the dread that someone might kill him at any moment. If dying violently was inevitable, he reckoned, he might as well resign himself to it. He girded himself mentally against the nerve-racking despair of constant panic. “He was philosophical about his death,” Andrew Young would recall. “He knew it would come, and he just decided, you know, there was nothing to do about it.”

When President Kennedy was slain in 1963, King told his wife, Coretta, that he expected the same fate for himself. If the president had not been safe from an assassin’s bullet, King confided to his aides, neither was he. From the time John Kennedy was killed, Andrew Young would remember, “Dr. King just felt, when your time comes, if the president can’t be secured with hundreds of Secret Service, there’s nothing that two or three officers are going do with us.”

As he traveled around the country, King declined many offers of police security. He did not want a phalanx of police hanging around him. He believed that having armed officers in uniform standing vigil over him would send the wrong message. His was a message of nonviolent protest, a Christian tenet of turning the other cheek to hatred and violence. It was a credo that clashed with the open display of armed police guards ready to shoot.

To look to the Memphis police in particular for protection must have struck King as a doubtful proposition. Undercover officers on Holloman’s force were infiltrating the meetings of striking garbage workers and their supporters. The police were suspect in the eyes of the strike supporters for having employed harsh tactics to quell the rioting on March 28. Though many marchers had been teargassed and beaten, King had not. All the same, considering the conduct of the Memphis police that day, he had reason not to trust them.

In the days before King returned to the city on April 3, the number of death threats spiked higher. According to Holloman, the authorities received a flurry of telephone calls to the effect that King “would not live through” the march of April 6. Holloman said in court testimony on April 4 that he was “very much concerned” about King’s safety.

The surge of threats and the rioting on March 28 had caused Holloman to reconsider his position that King did not warrant any special protection. Under the circumstances the police director had determined that prudence dictated a security detail for him. So it was that, when King arrived at the Memphis airport on April 3, Inspector Donald Smith’s detail of four officers had been there to guard him.

Smith and the other officers remained on the King watch all day. At 5:05 p.m., Smith called headquarters for permission to “secure the detail” — police-speak for “end the mission.” Permission was granted. That concluded the security for King, not just for that day but indefinitely. There was no security detail assigned to protect him that night or the next day. The security shield for King, such as it was, had been in effect six hours and thirty-two minutes.

Why the security detail was disbanded at 5:05 p.m. on that Wednesday is a mystery. The after-action report, the police department’s most complete review of its security for King during the visit in April 1968, does not say why. The report notes only that Chief J. C. MacDonald, who worked under Holloman’s command, ordered the security detail to stand down at 5:05 p.m. Holloman would say later that he did not remember having authorized the stand-down. In his testimony he conceded that abandoning security on the afternoon of King’s first day in Memphis was “not proper considering the circumstances.”

Holloman’s testimony revealed the low priority that he had assigned to King’s security. He said that he had not involved himself in the particulars of the security plan for King on April 3. Nor had he monitored how things were going. Holloman’s priority was surveillance, not security. The surveillance by officers Ed Redditt and Willie Richmond did not end on Wednesday afternoon. They returned to their post at the firehouse across Mulberry Street from the Lorraine the next morning.

Holloman acquired his training in law enforcement during his decades with the FBI under the surveillance-prone management of J. Edgar Hoover. Holloman joined the bureau in 1937 after graduating from the University of Mississippi Law School. He rose through the ranks, heading regional bureaus in Atlanta, Memphis, Cincinnati, and Jackson, Mississippi. In 1956, Hoover named him “inspector in charge” at FBI headquarters. In that position he oversaw FBI personnel for eight years, reporting to Hoover.

After Mayor Loeb appointed him to head the Memphis Police Department, in January 1968, Holloman moved swiftly to create an Inspectional Division. In effect it meant a new emphasis on covert operations. As he would explain later, Holloman had a “special interest” in developing the department’s intelligence capacity.

Holloman was taking a page from Hoover’s playbook. The Inspectional Division was the Memphis version of the FBI’s Intelligence Division. At Hoover’s direction the FBI had launched, in the late 1950s, a secret program known as COINTELPRO (Counterintelligence Program). COINTELPRO officially existed to investigate communist activity, but it morphed into a mammoth “dirty tricks” operation to thwart supposedly radical elements in the civil rights movement. King was a major target.

When the garbage workers went on strike, Holloman assigned Redditt and Richmond to surveillance. He assigned Marrell McCollough, a recent police recruit, to undercover work, tasking him to infiltrate the Invaders. Like Redditt and Richmond, McCollough was an African American. No African Americans were assigned to Detective Smith’s security detail.

Holloman’s emphasis on surveillance over security in King’s case seemed in line with his enthusiasm for counterintelligence. In defending his policy years later, Holloman would say that, had King agreed to cooperate, the police would have provided security for him the whole time he was in Memphis. Without that cooperation, Holloman said, he did not think that a security detail would have served any purpose.

In some other cities, however, law enforcement officials did not take no for an answer. They persuaded King to cooperate or provided security regardless. FBI records show that security measures for King were put into effect in a number of cities — from Milwaukee to Cincinnati, Boston to Las Vegas.

Even in die-hard segregationist Albany, Georgia, Chief Laurie Pritchett commenced round-the-clock police protection for King. Though King objected, Pritchett ignored him. The chief recognized the great risk to his city and his reputation if the nation’s leading civil rights champion should die a violent death in Albany. According to an account by historian Stephen Oates, Pritchett declared that if King were murdered in Albany, “the fires would never cease.”

In 1964, during King’s visit to Las Vegas, sheriff ’s deputies kept him under constant guard by day, and they stood vigil in his hotel suite at night. In Los Angeles on February 28, 1965, one hundred police officers were deployed to protect him. In Charlotte, North Carolina, where he attended a two-day conference in September 1966, Police Chief John Ingersoll assigned fourteen African American policemen to a security detail for King. As he left a speaking engagement, the officers held hands and formed a human corridor to shield him.

As recently as February, a few weeks before King’s return to Memphis in April, police officers stood guard in the hallway leading to his room at the Sheraton Four Ambassadors Hotel in Miami. Apparently alarmed by death threats, the police prevailed on King to cancel a speech scheduled at Miami Beach and remain in the hotel. King complied. Billy Kyles, the Memphis minister who was at the conference, would recall: “The Miami police begged Martin not to leave the hotel because there were so many threats against him. So we stayed inside.”

That’s the sort of caution that Holloman’s predecessor as head of the Memphis police, Claude Armour, had exercised during King’s 1966 visit to Memphis. In the early 1960s, an era of court-ordered desegregation of schools and other public facilities, he decreed that his officers would follow the law and prevent any outbreak of violence. In the words of Maxine Smith, the executive director of the Memphis branch of the NAACP at the time: “He let his force know that he would not tolerate anything. He was going to see to it that those kids got to school and got home safely, and he did that.”

Under Armour’s stewardship of the department, however, allegations of police misconduct against African Americans did not cease. Maxine Smith accused the department of arresting blacks without cause in some instances and mistreating them. Smith said, “Police officers can do whatever they want to do under the guise of being police officers.” The term “John Gaston turbans” came into currency among the city’s defense lawyers. It was a reference to the many swaddled heads of blacks beaten by police and treated at the city’s public John Gaston Hospital. Young blacks had another term for the police violence: blue crush.

An incident during the summer of 1967 buttressed the claim that police, under Armour’s stewardship, were brutalizing blacks in Memphis with impunity. One sweltering night the police arrested the wrong man for the robbery of a convenience store. That night Gregory Jaynes, a reporter for the Commercial Appeal, was working the pressroom at police headquarters. Through the wall he heard the police walloping the suspect in a room next to his. He grabbed a telephone and called Barney DuBois, the paper’s rewrite man. “I put the receiver to the wall so Barney could hear the beating and back me up,” Jaynes would relate years later. His story ran on the front page of the Sunday paper. Four police officers were suspended. There was a civil service hearing, but the officers were not prosecuted. “They let the cops go,” Jaynes would recall.

Despite the department’s mixed record on racial matters under Armour, his handling of security for King reflected a caution that would be lacking in the department under Holloman. In June 1966 King operated out of Memphis while he took part in a march across Mississippi begun by James Meredith, the first black student admitted, in 1962, to the state’s flagship university at Oxford. In his home state Meredith was staging what he called a “march against fear” to combat racism.

Armour was determined that no harm would come to King while he was in Memphis. He ordered a security detail of eight African American officers and issued strict instructions: they would keep King safe, or there would be hell to pay. Jerry Dave Williams, a black homicide detective, was put in charge. “We would go in and check the rooms, make sure the telephone wasn’t bugged, check under the beds, check everywhere. Then I would assign two officers outside his door. We would take turns every two hours through the night,” Williams would say later.

Detective Redditt was one of the eight officers in Williams’s detail. Armour took it upon himself to issue orders to Redditt. He summoned Redditt to his office. Redditt would remember Armour saying, “This man is an international figure, and you better not let anything happen to him. If something happens, you lose your badge.”

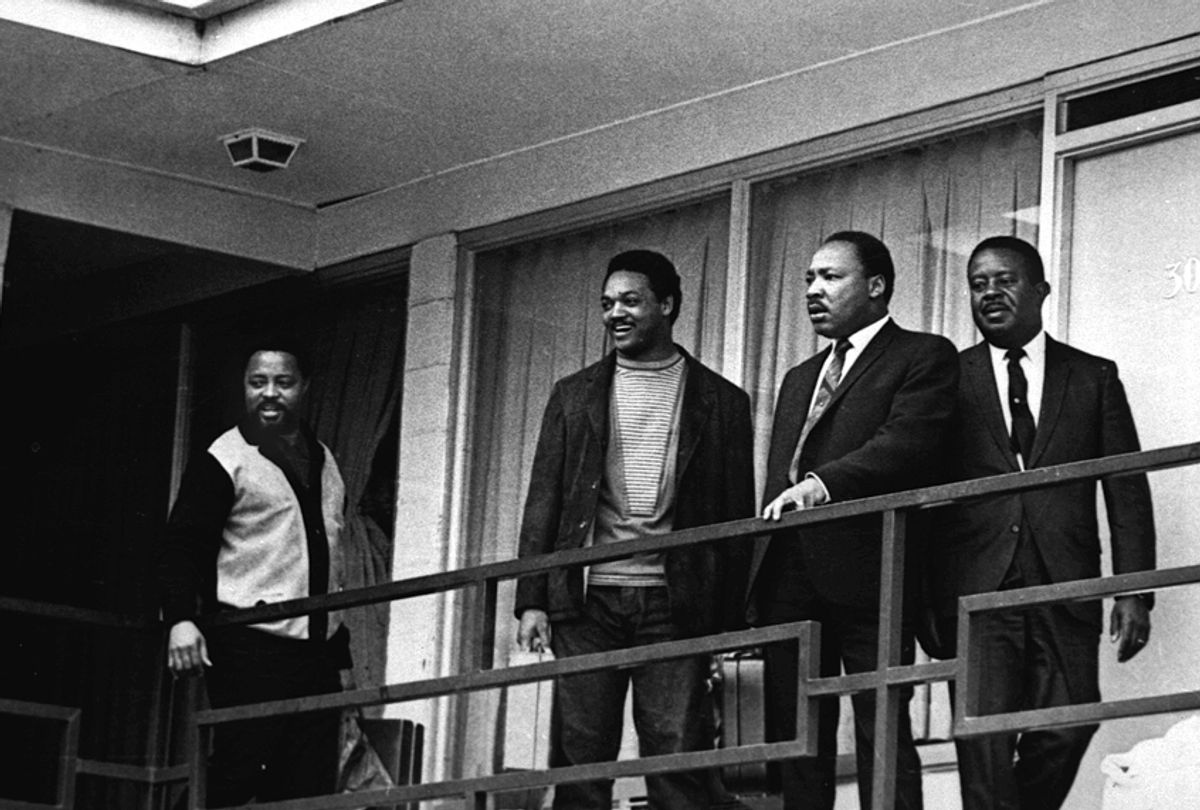

Guarding King had been unlike any other duty that Detective Redditt had performed as a police officer. King was staying at the Lorraine, where he had his customary Room 306 on the second floor. Wiry and fleet-footed (he had been a star sprinter on the track team at Manassas High School), Redditt had positioned his body as a human shield for King.

When King would leave his room to descend the open stairway to the ground floor, Redditt and other officers in the security detail were standing by. In Redditt’s telling: “We had to put our bodies around him and walk him down the stairs.” One morning, while King was eating breakfast, Redditt joked about all the trips up and down the stairs. “Why don’t you get another room?” he asked King. “It’s killing me walking up and down those steps.”

But Holloman did not follow Armour’s example. He did not see security for King as a critical matter demanding his close attention and scrutiny. In sharp contrast to Armour’s diligence in safeguarding King from harm, Holloman’s attitude was passive, halfhearted. As a consequence, King was in greater jeopardy on April 4, 1968.

Excerpted from "Redemption: Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Last 31 Hours" by Joseph Rosenbloom (Beacon Press, 2018). Reprinted with permission from Beacon Press.

Shares