There’s something charming and retrograde about the shrieking chorus that erupts online every time a major newspaper or legacy magazine hires some new dumbass to write opinions a few times a week. We all get to pretend that any of this still matters, that it’s not all just whistling into the void in a universe where a functionally illiterate American president gets all his information from a garish morning program, and your 60-something moms and dads receive their news from chain-letter-quality Facebook memes. Even those of us who still peruse the opinion pages can’t remember the last thing we read there. Even those of us who write this stuff are pressed to pretend it’s anything other than more frothy ephemera bobbing on the surface of a vast, rising ocean of content.

Many of the most loudly contested recent hires have been of so-called Never Trump conservatives, a cohort of exactly four-dozen people in three zip codes. Fortunately for them, they do have a natural constituency, which consists entirely of the editors of prestige publications. These are people — both the posturing writers and the editors who hire them — with an abiding commitment to the line that our current president represents the inception of something entirely new and gross in our political system, which allows them to conveniently elide the racist savagery of American politics, and American conservativism in particular, more or less from the get-go.

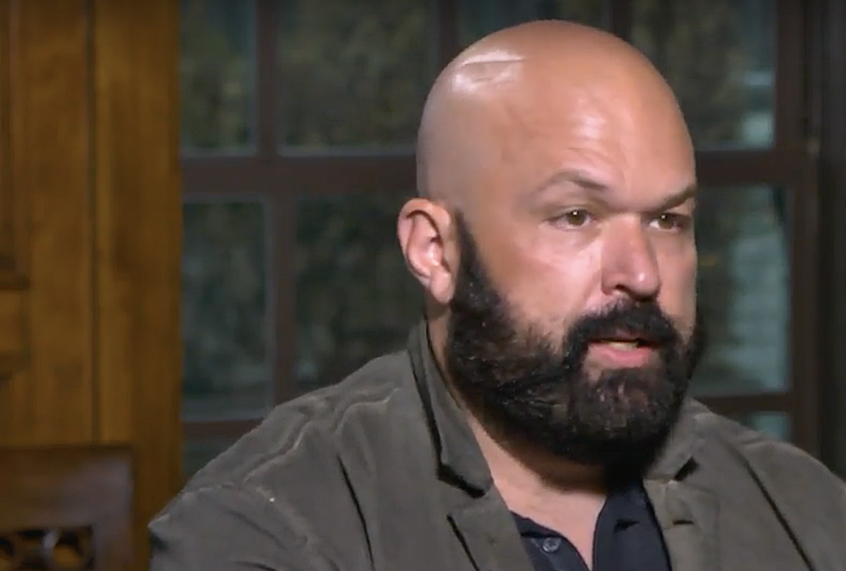

The Atlantic, for instance, whose stable of writers includes former George W. Bush speechwriter #NeverTrumper David Frum, just hired Kevin D. Williamson. A former National Review writer, Williamson was swiftly taken to task on Twitter for proposing that women who have abortions should be hanged, and for once describing an African-American boy as a “three-fifths-scale Snoop Dogg.” (He has since deleted his account.) You may recall another well-known American document that refers to black people by this percentage. Williamson drops this deliberate provocation (he is daring you to call him racist, so he can deny it and accuse you of a deliberately uncharitable reading) immediately after describing the boy as “raising his palms to his clavicles, elbows akimbo, in the universal gesture of primate territorial challenge.” (“Well, humans are primates,” he would argue, if you bothered to point out that this, too, is racist trash.)

Williamson has written that dying towns should be left to die, that mobile rootlessness is the key to economic prosperity, and that price gouging after natural disasters is fine and good. These would appear to cut slightly against some of the central rhetorical commitments of conservative writing and thought, which valorizes small-town America, imagines church and family as the central institutions of communal life, and proposes that private charity could pick up the slack for disaster relief and health and human services. We should instead untangle our social networks, abandon our congregations and let Main Street go to seed as our tiny nuclear families blast around America, from one city to another, in search of some tenuous at-will job. How will we pay for the U-Haul, the motels, the first and last months’ rent? Who cares. The truth is that this only seems to cut against conservativism, whose ideals about community were never more than rhetorical, except of course when it came to race, for which the specific boundaries of particular communities retain a totemic power.

Williamson wasn’t the worst writer the Atlantic could have hired. At the National Review, where you can also encounter the fatuous Jonah Goldberg or the perpetually morally panicked David French, he is very nearly reasonable, even if he still appears slightly mad to those of us outside of the asylum. He’s merely a tedious crank. But a lot of tedious cranks seem to be popping up in the upper echelons of opinion journalism these days, and it does well to ask why.

The editors and publishers will tell you that it is so that their overwhelmingly liberal audiences may be exposed to new ideas, as if readers of the Atlantic are unaware that conservatives think affirmative action is bad and subscribers to the New York Times don’t know that there are people who pretend to think that climate change is phony. And if you are the sort of person who complains about these hires online, someone will surely pop into your Twitter mentions to remind you that the outrage machine drives lots of clicks and page views.

The truth, though, is that these columnists are all hired as part of a project of desperate make-believe, in which it is possible to imagine that Donald Trump and our present politics really are a singular event, a historic deviation. In their fantasy, there remain two broadly similar and functional political parties whose respective ideologies meet in a nebulous but desirable middle, wherein reasonable men and their reasonable institutions can yet function as they ever have. It’s a fairly rosy portrayal of American political history to begin with, but there was at least a sense that it was superficially, if only superficially, true. This genteel fiction permits the mandarins of respectable media to indulge the most preposterous fiction of them all, which is that the modern conservative movement in America isn’t absolutely and irredeemably deranged.

This is not to overcredit a deeply compromised and corrupt American liberalism, especially in the form of a Democratic Party that more often than not resembles a finishing school for communications professionals and future Wall Street placeholders. But only if we pretend that a tiny cadre of idiosyncratic urban conservatives are in some way representative of even a plurality of conservative thought in this country can we imagine that at a root level, this all amounts to differing attitudes about market incentives and land use policies — that it was ever about any of that to begin with. If that is not the case, then it throws into stark relief the broader identities of these publications as largely neutral arbitrators of a national conversation, and that might mean they’d face some moral obligation to pick a side.